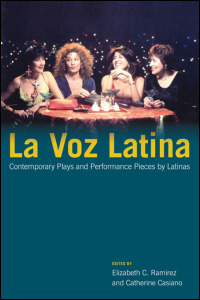

Elizabeth C. Ramírez is the is the fine arts specialist administrator with the Edgewood Independent School District of San Antonio, Texas, and co-editor of the new book La Voz Latina: Contemporary Plays and Performance Pieces by Latinas.

Elizabeth C. Ramírez is the is the fine arts specialist administrator with the Edgewood Independent School District of San Antonio, Texas, and co-editor of the new book La Voz Latina: Contemporary Plays and Performance Pieces by Latinas.

*****

Q: You have co-edited a collection of plays by Latinas. You and Catherine Casiano have chronicled women’s plays and performance pieces and given each playwright a forum on which they tell their own stories in their own words and provide a glimpse of the kinds of stories they have created for the stage. Where does your own stage life begin?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: My family was very attached to the church in our barrio. My father was a house painter, and he and my mother both valued education and performance. When a new school opened at our Catholic church, we were enrolled. A young Belgium priest staged elaborate productions, and I was often cast. An unusual ability to memorize poems, stories, dramatic pieces made me a ready performer for any visiting church leader or special events. Once we moved, there was only one opportunity when I took theatre in h high school, and despite being one of the few Chicanas in the class, the one Chicana nun cast everyone but me for our big production of House of Bernarda Alba, the usual play for all-girls schools. Fortunately, the part of the senile grandmother became mine when the girl with the part did not learn her lines. I, of course, had all of the lines down already. However, history was always the biggest draw, and when I discovered I could study theatre history and criticism and teach as well, I found my calling. Perhaps the best part came when I was able to study with the recognized leading theatre historian, Oscar G. Brockett. When Brock was working on one of his countless editions of his History of Theatre, he said to me: “If I can write a whole history of Theatre, I don’t see why you can’t write one about Spanish-language performance in the U.S.” I have done so ever since, both teaching multicultural theatre and working professionally as a dramaturg, with an emphasis on Latina performance. I was also the Director of Ethnic Studies at the University of Oregon and a fellow in Dramaturgy at the American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Q: More and more we hear about the growing number of Hispanics in the U.S. Where did you begin your search for Latina playwrights? Are they really out there? Why is this history important?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: As the United States was undertaking a new census in 2010, we knew that the Hispanic population in the United States had undergone tremendous growth since the 2000 U.S. Census. According to The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief, out of 281.4 million residents reported in the 2000 census (excluding the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Island Areas), 35.3 million, or 12.5 percent, were Hispanic, of which 7.3 percent were Mexicans, 1.2 percent Puerto Ricans, 0.4 percent Cubans, and 3.6 percent were “other Hispanics.” The 2000 census data forecast a new picture of the nation. Not only were these numbers showing a firm presence but also continual growth. Unquestionably, the growing number of Latinas/Latinos in the United States makes it vital that the individual contributions of each be understood, and it is by seeing their similarities and differences that this can be accomplished. Thus, we collected diverse work by Latinas, presenting both English and bilingual play texts that aim to inform others about this remarkable group in the U.S.

Q: Your collection of plays includes 12 little gems of varying styles, forms, themes and genres as well as commentary by two leading spokeswomen of contemporary theatre. How did you decide which playwrights you would highlight in this manner?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: This anthology is distinguished by its variety in form and content. Through the creative expression found in this compilation, we examine eleven playwrights who are also theatre practitioners to varying degrees. Perhaps most often, women have told us that they produced their stories in order to insure that their voices would be heard. Of the more than twenty Latina origins found in the United States, this first volume features Cuban, Puerto Rican, Chicana, and Dominican voices, as well as those whose origins are a blend of more than one background, with expectations of including additional voices and worldviews in future volumes.

Q: Which piece is the most compelling to you personally?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: Cherríe Moraga, the highly acclaimed feminist and playwright, whose work includes the acclaimed anthology, This Bridge Called My Back, co-edited with Gloria Anzaldúa, and numerous plays, sent us a small piece entitled Waiting for Da’ God. Here we glimpse this playwright’s seminal concept of the struggles many of us face today. Moraga gives us a poignant piece that combines humor to tell us about the very difficult issues of aging, children caring and not caring for their elderly parents, and the tragedy of lost love. The futile waiting for “God,” the son, provides the background for the tantalizing hints of complex relationships that the playwright would later develop into fully fleshed-out characters. During the entire time that I was working on this collection with Catherine, we were losing my father, and my mother also began her own debility. With five siblings, the experience was so similar, that is, one son completely devoted to both parents, while the other never coming around. Hearing my mother’s yearning for the one she can barely even envision anymore is heart-breaking. Even more so, when it seemed women I encountered everywhere were telling me the same story, “there is one in every family,” was the third sister that has used every excuse imaginable to stay away, yet, just as Cherríe’s mother yearned for “Da’ God,” as her unseen savior who never comes, the devoted daughter stayed with her, caring and comforting her until the end.

There is another play, Milcha Sanchez-Scott’s Roosters, that has had perhaps the most extensive stage life than any play by a Latina and has been extensively anthologized as well. While some readers of the manuscript questioned its inclusion, we held it in highest esteem because of its significance in the entire repertoire of plays by Latinas. Both Cherríe and Milcha had been protégés of Maria Irene Fornes, and Irene stands out in this entire history. When we did not get the rights for Irene’s play, we chose to pay tribute to her by highlighting two outstanding playwrights who had been influenced by her.

Q: What makes a Latina play different from any other playwright’s work? What’s new about these women?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: The playwrights in this book show how they have drawn from their own families and friends in their surrounding communities in order to tell us their stories. Sometimes these stories are filled with humor and often they are very serious, giving us an entryway into their view of the world in which they live. We are introduced to and often are reacquainted with characters that we may have know about before, like fathers, mothers, family, and friends in our barrios, but they are given broader dimensions than we have seen before. We view them from the women’s cultural and ethnic perspectives, often crossing national and international borders.

Q: Your collection features topics related to Creating a Performing Voice and themes of family, religion, and community; Chicanas and Chicano theatre and staging identity; the indigenous and staging myth; race matters, searching for “home” and how we get there,” and ending with commentary on Latina Theatre in the U.S. Why did you choose to organize your book by special topics?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: Each section delineates the ethnic and cultural roots of the artists that serve as the framework in which their works are situated. The plays are set against the larger historical or genealogical narrative in which they appear. Within the individual entries, while we have strived for uniformity, each playwright tells us her story in her own words, and the entries end up quite distinct from each other.

Q: What other features make your book essential reading? How does your book broaden the annals of American theatre history?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: We found so much variety in how the playwrights used Spanish and English that we focused more and more on the duality of language. Thus, we arrived at using both English and Spanish for each subheading, which to us seemed an appropriate way to pay homage to our own long lineage of Spanish-speaking ancestry, bringing into prominence the bond that we held with the playwrights we had worked with for so long for this collection.

We were also privileged to be able to include commentary by Kathy Perkins and Caridad Svich on the status of Latina theatre in the U.S. Both are highly recognized women who have made great strides in bringing the much needed attention to plays by women of color. Caridad Svich’s work with NoPassport has been both nationally and internationally influential. This highly prolific playwright has become a significant force in Latina/Latino theatre for far more than her expansive body of dramatic work as the founder of NoPassport, an unincorporated theatre alliance and press devoted to expression and advocacy for crosscultural diversity and difference in the arts. Kathy A. Perkins brings an even more diverse perspective, given the groundbreaking collection of plays she co-edited with Roberta Uno, Contemporary Plays by Women of Color: An Anthology (Routledge), and her ever-expanding work in the field and outstanding voice on the topic of women of color.

Q: What excites you the most about this collection and the many years you and Catherine devoted to it?

Elizabeth C. Ramírez: These women just want to make the best art that they can, and they are devoted to their stories, to their family, their culture, and their heritage. It is just hard work to engage audiences, and they believe in their long lineage of performance and telling their history. I hope that we have made a difference in bringing their work to others. They deserve the widest audience possible. There is little reason to doubt that these Latinas will continue to be productive in their creative work, and for us this volume should serve as a springboard for theatre practitioners and others to broaden their season in terms of world theatre. Whether we are introducing or re-introducing these works and these artists, it is up to theatre practitioners to reach beyond this volume to the ever-growing body of work by these women.