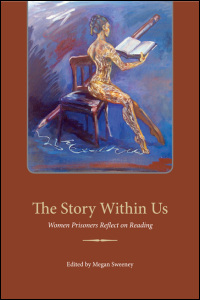

Megan Sweeney is an associate professor of English Language & Literature and Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan. She answered our questions about her new book The Story Within Us: Women Prisoners Reflect on Reading, which explores the reading experiences of incarcerated women.

Megan Sweeney is an associate professor of English Language & Literature and Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan. She answered our questions about her new book The Story Within Us: Women Prisoners Reflect on Reading, which explores the reading experiences of incarcerated women.

Q: What inspired you to research and write the book?

Sweeney: I have been involved with women prisoners for more than twenty years, first as a social worker, then as a volunteer GED tutor and book club facilitator, and finally as a scholar researching women’s reading practices in three different prisons. In conducting research for my first book, I wanted to know something about the thoughts and experiences of women who live outside the frame of daily reference for many Americans.

I wanted to know whether reading and a love of books might help imprisoned women—as it has helped me—to discover their place in the world, gain insight about their pasts, experiment with new ways of being, and conjure possibilities that do not yet exist. Furthermore, I wanted to bring into relief some of the texture of imprisoned women’s lives, to counter our reductive cultural narratives about crime, victimization, responsibility, healing, and justice. I also wanted to bring women to life on the page—through their own words—as thinkers, readers, family members, and friends whose efforts to cultivate rich lives and meaningful relationships continue even when they remain permanently out of public sight. Moreover, I wanted to foster dialogue among readers and thinkers on both sides of the prison fence. And when all was said and done, I wanted to offer imprisoned women an image of themselves that reflects back to them the creativity, strength and tenacity, intelligence, and deep humanity that I witnessed in their engagements with books.

The weight of this wanting is too heavy for one project to bear, and as I was

writing my first book (Reading is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons), I felt totally overwhelmed by all of the stories and insights that I could not include in the space of a single book. A helpful mentor suggested that I write two books instead of one, including a volume composed solely of interviews with women prisoners. I followed her advice, and The Story Within Us is the culmination of this two-book journey.

Q: How did you meet the women prisoners?

Sweeney: Over the course of several years, I conducted extensive individual interviews and group discussions with ninety-four women imprisoned in North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Each woman participated in one life narrative interview, one to two interviews about reading, and four to seven group discussions of books; in total, I conducted two hundred and forty-five individual interviews and fifty-one group conversations.

I solicited participants for my research by asking prison administrators to post fliers advertising my study in each living area and common area, in the educational programming area, and in the library. In the Pennsylvania prison, my study was also advertised on the television channel that broadcasts news within the institution. I invited women with at least an eighth-grade reading level to participate in interviews and book

discussions related to women, crime, punishment, and/or healing; although I did not formally assess women’s reading levels, their self-assessments and actual ability to complete the readings sufficed for regulating women’s involvement in the study. On

the flier, I stated that I wanted to learn about books that are popular in prison, the role that reading plays in women prisoners’ lives, and prisoners’ ideas about crime, punishment, and healing. At each facility, I held a meeting for all interested participants in which I explained the aims and methods of my study, discussed the consent form, and answered questions. Women who decided to participate signed a consent form at the conclusion of the meeting.

Q: What did you learn about reading and education in the U.S. penal system?

Sweeney: The narratives featured in The Story Within Us help to tell a rarely told story about the crucial intellectual work that prisoners perform in settings that are far from conducive to reading and contemplation. Over the past forty years, prisoners’ opportunities for reading and education have sharply declined. As the prisoners’ rights movement of the 1960s and ‘70s gave way to the retributive justice framework of the 1980s, prisons radically reduced their library budgets, converted library space into prison cells, and installed televisions as a pacification tool.

In the prisons where I conducted research, the libraries are now funded entirely by revenue from the vending machines, and that funding is shared among several programs in the prison. Furthermore, due to security concerns, prisoners can only receive brand-new books sent directly from publishers, which means that buying books is far too expensive for most women. Even women’s access to prison libraries is limited; because some penal officials fear that libraries serve as a “gay bar,” women must sign up one week in advance to visit the library, and their visits are limited to thirty minutes.

Many books are also banned, from Harry Potter (because it depicts witchcraft) to medical texts (because they include images of women’s breasts). Racialized restrictions on reading, which have been in place since the birth of the penitentiary, likewise delimit prisoners’ access to books. As one example among many, while allowing Ku Klux Klan publications such as Negro Watch and Jew Watch, the Texas penal system has banned Toni Morrison’s novel, Paradise, on the grounds that it contains “information of a racial nature” that seems “designed to achieve a breakdown of prisons through inmate . . . strikes or riots” (Morrison letter 154). Penal officials fear that Morrison’s references to the KKK and the Civil Rights and Black power movements will lead to a “breakdown of prisons,” yet they argue that Klan publications do not threaten their ability to “maintain . . . order and security” (Vogel 17).

Prisoners’ opportunities for reading have been further curtailed by recent legal

precedents. In its 2006 decision Beard v. Banks, the U.S. Supreme Court deemed it constitutional for a Pennsylvania prison to deny secular newspapers and magazines to prisoners in its long-term segregation unit, on the grounds that this denial of reading

materials serves as an “incentive[e] for inmate growth” (qtd. in Breyer 2). Because these prisoners have no access to television, radio, telephone, or visitors, they receive no current news. The two dissenting justices insist that access to the full range of ideas is crucial for preserving one’s sense of humanity and citizenship, but the majority opinion deems such claims moot when “dealing with especially difficult prisoners” (Breyer 11). The fact that African Americans and Latino/as are overrepresented in supermaximum prisons makes this denial of citizenship even more troubling. Exacerbating all of these trends, Congress eliminated Pell Grants for prisoners in 1994, which sparked dramatic cuts in all levels of educational programming.

Dominant depictions of prisoners rarely emphasize their status as readers, let alone as thinkers; reading tends to be associated only with political prisoners or self-identified intellectuals. However, even in the midst of these severe restrictions, many prisoners manage to maintain vibrant intellectual lives. In fact, according to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy, incarcerated women and men who have earned their GED “read more and watch less TV” than their non-incarcerated counterparts (91). And within this pool, 50% of incarcerated people versus 22% of non-incarcerated people report reading books on a daily basis, and 47% of incarcerated people versus 39% of non-incarcerated people report reading newspapers and magazines on a daily basis (81-82). Drawing on the limited reading materials available to them—including devalued popular genres—women involved in my study perform crucial forms of self-reflection and self-creation, learn from others’ perspectives, develop empathy across lines of difference, and in the words of one reader, strive to “feel a part of society as a whole.”

Q: Why did you focus on women prisoners?

Sweeney: As a woman involved in my research observed, “Women in prison are pushed aside because there are less of us than men, but our stories are just as important even if men outnumber us.” Although women make up only about 7% of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons, that figure translates to 113,000 women, which is more people than a Division I football stadium can hold. And if we consider the long-term impact of incarceration in the lives of these women, their families, and their communities, this number seems large, indeed. The number of women in prison also continues to increase; in fact, it was seven times larger in 2004 than in 1977, largely due to draconian and racialized policies for prosecuting drug crimes (Sabol et al. 3).

My book draws particular attention to the experiences of African American women. You hear a lot about black men in prison, but black women are one of the fastest growing yet

least acknowledged populations in U.S. prisons. In recent years, some scholars and activists have produced groundbreaking work about women of color’s experiences in the criminal justice system, but explicit discussions of black women remain relatively scarce in scholarship about crime. This erasure of African American women’s experiences is especially troubling given the dramatic increase in rates of incarceration for women in general, and for African American women in particular. African Americans represent about 13% of the U.S. population, but black women represent 28% of all incarcerated women, and they are three times more likely to be incarcerated than white women (Sabol et al. 6, 8). As the narratives featured in The Story Within Us illuminate, mass incarceration is fundamentally a matter of “racial justice” (Alexander 9) for women, too.

By foregrounding the reading practices of African American women, my book also addresses the need for more inclusive scholarship about women’s reading practices. From Janice Radway’s groundbreaking Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature, to Elizabeth Long’s Book Clubs: Women and the Uses of Reading in Everyday Life, existing studies typically feature white, middle-class women in exploring how women negotiate their subject positions through engagement with books. My work

responds to Elizabeth McHenry’s call—in Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies—for scholarship that counters the historical invisibility of black readers and investigates nonacademic venues in which African American literacy practices have flourished.

Q: Did you face any resistance from the prisons or prisoners while researching the book?

Sweeney: I did not conduct research in federal prisons because they present particularly difficult barriers to access. I attempted to conduct research in ten different states, but seven of those ten denied me access to their penal facilities: Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, and New York. Three states granted me acces —North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—but one of these states did not permit me to audio-record my interviews or group discussions with prisoners, and penal officials in all three states prevented me from discussing particular kinds of books with incarcerated women.

The prisons featured in my study ban periodicals, pamphlets, and books related to racial

and class struggle. They also ban most books and periodicals that address contemporary U.S. punishment practices. In fact, one of the prisons refused my request to share my book with the women featured in it; they will not allow me to return to the prison for a discussion of my book and will not even allow me to send copies to the interviewees. Furthermore, the featured prisons forbid books that discuss the manufacture of weapons, terrorist tactics, witchcraft, magic techniques, satanic rituals, rape, or homosexual sex, as well as books that include nudity, explicit sexual material, or pictures of guns. Penal officials also ban genres and books that they deem particularly controversial or counter-cultural.

While I was conducting research, the Ohio prison banned Maya Angelou’s Phenomenal Woman: Four Poems Celebrating Women because the most recent edition includes Paul Gaugin paintings that feature female nudity. The Pennsylvania prison forbade us to discuss Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion, a non-fictional work that some women wanted to read for a group discussion. Officials in both Ohio and Pennsylvania also severely restricted our discussions of the highly popular genre of urban fiction. Although we had received permission to discuss a few urban books, an Ohio prison official burst in to stop one of our discussions after learning that the books were published by Triple Crown Publications, a publishing firm founded by a former prisoner. The official told me to collect the books and immediately remove them from prison grounds, as if, one prisoner noted, they were “a bomb that no one can touch.” Since we were not permitted to read any additional urban books, I asked if we might have a group discussion about two particularly popular books that most of the participants had already read. A penal official insisted, however, that “there can be no discussion of the work.”

A devastating incident from my research further illustrates penal officials’ desire to keep prisoners’ reading under their control. A few women involved in my study told me about their participation in a small reading group run by a member of the prison staff. Members of the group were reading contemporary novels and well-known non-fiction texts, discussing current events, learning new vocabulary, and writing reflections about concepts such as freedom. Upon the recommendation of one of the participants, I requested permission to interview the unit manager who started the reading group. The penal administration was not aware of the group until I brought it their attention, and much to my chagrin, they promptly shut it down because it was not operating under official approval.

Because involvement in my study was completely voluntary, I did not face any resistance

from women who chose to participate. On the contrary, women were eager for the chance to talk with me because I was not part of the penal system and was interested in hearing about their ideas and experiences. The interviewees were also very grateful for the chance to read and discuss books, and to share their ideas and experiences with each other.

Q: Each chapter features a Life Narrative and a Reading Narrative. How do the two of these overlap, if at all?

Sweeney: As many scholars argue, all of us adopt culturally available narratives and models in crafting our identities. We “take up bits and pieces of the identities and narrative forms available” and fashion them into our own stories (Smith and Watson14).

Because prisons offer few resources for helping women to come to terms with their pasts and reshape their futures, reading plays an especially important role in some prisoners’ processes of self-reflection and self-creation.

Women who are reckoning with the weight of particularly difficult experiences can feel a pressing need to find something useful—a bit of advice, a sense of companionship, a glimmer of insight—in reading a book. Encountering a character who inspires them, demonstrates a capacity for change, or serves as a mentor, model, or friend can seem vitally important to women who feel an urgent desire to change but a deep uncertainty about their ability to do so.

Furthermore, identifying with a book character enables some women to validate their emotions and experiences by situating them within broader social and historical contexts. This process allows women, in turn, to reckon with suppressed emotions, tell formerly silenced stories, view their pasts within a new frame, and become authors of their own futures. Reading also enables women to engage with difference and to develop understanding and empathy for those whose perspectives differ from their own. In the words of Deven, a thirty-six-year-old white woman, “We’ve just read five different books of women telling us about themselves in like seven hundred different ways. And each of them . . .has been a wonderful learning journey for me of getting more in touch with my inner self and my inner power source, and having some different ways to look at some situations instead of starting with that tunnel vision that I’ve known for so long.” Deven goes on to suggest that engaging with others’ narratives introduces an array of possibilities from which women can choose as they undertake the ongoing work of crafting their life stories. “All these [authors] had stories inside of them,” Deven explains. “All us women have a story within us, and it’s just which way do we choose to write it?”

One woman featured in the collection offers a particularly moving illustration of

how prisoners use others’ stories to mediate their own experiences. This reader told me at the start of her individual interview that she had never had “more than twenty minutes” to recount her life story, and she then spoke very emotionally for almost two hours. Yet in reviewing her interview transcript, she carefully redacted almost all references to pain, including her extensive experiences of sexual and physical abuse. This woman seemed to find it overwhelming to encounter her painful history on paper. She nonetheless loves books about women whose lives mirror her own. Reading others’ stories seems to provide the necessary distance for this woman to encounter herself.

Q: Was there a common favorite book or type of book?

Sweeney: Many women in prison enjoy reading books that are also popular outside of prisons, including books featured on “Oprah,” biographies and autobiographies, “true crime” books, and bestsellers by authors such as John Grisham, James Patterson, Stephen King, V. C. Andrews, and Danielle Steel. In my first book, Reading is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons, I discuss women’s engagements with three particularly popular genres: self-help books by authors such as Joyce Meyer and Iyanla Vanzant; urban fiction, which features African Americans involved in street crime; and narratives that address issues of victimization, such as T.D. Jakes’s Woman, Thou Art Loosed!.

Q: Do you have a favorite narrative in the book?

Sweeney: As you might imagine, choosing which interviews to include was extremely

difficult, and I am keenly aware of the many stories and reflections that will remain unheard. I selected the featured narratives, in part, because they represent a spectrum of women’s experiences. Seven of the featured readers self-identify as African American or black, three self-identify as white, and one self-identifies as American Indian. Ranging in age from twenty-seven to fifty-six, the interviewees have been convicted of a variety of crimes, and their sentences range from three years to life imprisonment. The featured women in also discuss a broad array of books, including popular genres such as urban fiction, legal thrillers, true crime, romance, science fiction, and Christian self-help books, as well as biographies and autobiographies, books about world religions, African American history, legal texts, and novels by Toni Morrison. Most importantly, the selected interviews offer compelling and detailed descriptions of women’s experiences and complex inner lives. All of the life narratives and reading narratives—and the women who offer them—continue to move, surprise, and inspire me.