This originally appeared in the Berkshire Jewish Voice (Oct 29-Nov.7, 2010; Vol. 19, No. 1)

This originally appeared in the Berkshire Jewish Voice (Oct 29-Nov.7, 2010; Vol. 19, No. 1)

*****

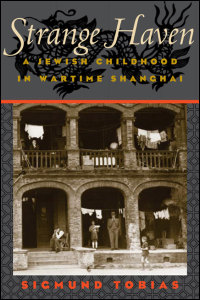

My parents and I survived the Holocaust by fleeing to Shanghai where we lived for a decade during the Second World War. Our survival in China, the life of that Jewish refugee community, and how I came to study in the Mirrer Yeshiva, which also fled to China, is described in my memoir of that time recently issued in paperback (Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in World War II Shanghai, University of Illinois Press, 2009).

My gradual loss of religious faith began after the end of the War and was stimulated by two events. First, was the Holocaust which we heard about after the end of the war. I learned that almost thirty of my aunts, uncles, and cousins in Poland – some in their infancy- perished in different camps during the war. Those who were not murdered in concentration camps, were killed in Poland when the Germans dragged Jewish men out of the synagogue during the second day of Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) services in 1939, drove them into the forest, and executed them. Second, my faith suffered another shock when we learned that the Yeshivas in Shanghai had received what was then substantial monetary support from the Vaad Hatzallah (an organization to rescue Jews from the Holocaust) throughout the war. Even though they preached charity the Yeshivas did not share their ample food supplies with Jews in need, despite the specter of malnutrition among the refugees.

After arriving in the United States, I broke away from Jewish religious organizations entirely. During college I was active in Hillel (Jewish college students organization) but never entered a synagogue voluntarily though, in order to please my parents I joined them for the High Holy Day services at their Orthodox synagogue. I am amused to recall that during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur I was more interested in the latest scores of crucial final season, or World Series baseball games that coincided with the High Holidays than in the prayers. It was clear that many others felt similarly, because the latest developments in crucial games involving New York area teams were circulated regularly among us during services.

After I was married, we did not join any congregation for almost thirty years. When our two daughters Susan and Rochelle were in elementary school, many of their friends attended Hebrew school and our children felt left out and wanted to join them. We were ready to pay the relatively steep Hebrew school fees for non-members, rather than get a substantial discount by joining a congregation, but asked our daughters to commit themselves to attend regularly so that the money would not be wasted. They were reluctant to make that commitment and never attended Hebrew school.

Susan and Rochelle attended services at the local Conservative synagogue on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), and my wife and I readily drove them there and picked them up after services. They also fasted on Yom Kippur, and we prepared dinners before and after Yom Kippur to facilitate their fasting. Our girls felt awkward about attending synagogue without us and urged us to join them, but we never did. We regularly contributed to appeals for Israel and for secular Jewish organizations, but did not join or contribute to any religious ones.

After my mother died, I tried to comfort my father by staying with him for the seven days of shiva (mourning). I participated in the morning and evening minyan in my parents’ apartment, and sat on the hard shiva stools when visitors came for condolence calls. A few weeks later, when my father visited us at our home in the New York City suburbs, I found some Synagogues with daily morning and evening prayer services, where my father and I could chant the Kaddish (prayer said for those who died) in memory of my mother. In one of these, a Young Israel congregation in Spring Valley, NY, the Rabbi, a short, bearded man, came over to welcome us during the morning service. He noticed that, unlike my father, I was not putting on tefilin (philacteries worn by men for weekday morning services) and offered to teach me how to do that.

“Thank you Rabbi, I know how.”

“If you forgot yours, I’ll be glad to lend you a pair of tefilin.”

“No thanks Rabbi, I would rather not.”

When we returned for the late afternoon and evening services near the end of the day, the Rabbi paused to deliver a short talk. This was clearly an unexpected occurrence judging from the look of surprise on the faces of congregation members. The Rabbi preached that it was a great mitzvah to honor one’s departed parent by chanting the Kaddish. However, he continued, that paled into insignificance compared to the mitzvah of putting on tefilin. My father’s face darkened with anger, but he said nothing until we got into my car after the end of the service. Then he looked at me and said evenly “We are never going back to that place.” I hugged him, and we drove home. We attended another synagogue during the remainder of his stay.

My father died three months after my mother had passed away while on his way to say Kaddish for her at morning services. The Cantor from my parents’ synagogue, in upper Manhattan, officiated at funerals because the congregation’s Rabbi was a Cohen and, according to Halachah (laws regarding Jewish rituals), was prohibited from being near a dead body or entering a cemetery.

My parents felt comfortable with the Cantor because they shared a common Polish background and they, like he, spoke Yiddish as their everyday language. The Cantor expressed his condolences to me in a perfunctory way. Since he knew my parents well, he did not need any information for the eulogy. He began by describing what an honorable Jewish man my father had been, and then continued, “It is doubly sad that Reb Moishe’s wife Freyda Rivka (my parents’ Hebrew names)” and motioning to me, “your mother died only three months ago, she was a virtuous woman.” He motioned to me again. “During the shiva for your mother I realized how well versed in Judaism you were, and how estranged you had become from it.” Pointing to my father’s coffin, he continued. “Now, in the face of this second tragedy, is the time for you to return to the full observance of your faith.”

I did not have to listen to the rest of the eulogy. I knew that the Cantor would extol the awesomeness of the faith and how critical it was for me to observe it fully. After we followed the coffin out of the funeral parlor two colleagues approached to offer their condolences. One, a former student of mine, was an ordained Orthodox Rabbi who chose an academic career rather than lead a congregation, and the second was an observant Conservative Jew. They both felt badly about the eulogy. The Orthodox main said “At a tragic time when you should be comforted, how could anyone try to make you feel guilty. It was shameful.”

“You know,” I responded, “it would be a lie to say that I expected it. But once he got into the eulogy, I knew exactly where he was heading. The saddest thing I can say about the Orthodox Judaism I know is that I was not surprised.” I did not enter a synagogue for the next thirteen years.

Three years after my father died, I was a Visiting Professor at Florida State University. One day the local newspaper published a photo showing a group of Jews affiliated with the University engaged in a prayer service for one of the holidays. The paper described the group as a Chavura (friendship group) and I paid no further attention to it. A student, who worked in the University laboratory with which I was affiliated, attended Chavura meetings regularly. I had mentioned my background in the Mirrer Yeshiva to him and he always urged me to come to Chavura meetings, but we never did. One day he again asked me to join the group, and mentioned that at the next meeting there would be a discussion of what being Jewish meant to Chavura members. My wife and I decided to attend that meeting, partially at least to prevent the student from pestering me further about attending Chavura meetings.

The meeting of about sixteen people was led by Michael Berenbaum, an ordained Rabbi, who was at Florida State to study for a doctorate in religion with Richard Rubinstein. People talked about their backgrounds in Judaism and I eagerly discussed my studies in the Mirrer Yeshiva and how I had become estranged from the faith as a result of the Holocaust and the events described above. “There is a huge contradiction in my Jewishness. I feel like one of the most Jewish people in the world, but trying to make me feel guilty so that I would return to the faith is repugnant to me, and has made me avoid any contact with Jewish organized religious groups, and even most Jewish organizations.”

The Chavura accepted my feelings and made me feel welcome. We then sang some songs and I was surprised at how eagerly I joined the singing, how moved I was by it, and how closely connected I felt to the group even though this was our first meeting. After that, we attended Chavura meetings regularly, joined by our two daughters when the group gathered for family occasions such as a community Seder (Passover service conducted at home). I actively joined in the Seder and enjoyed singing the old melodies and learned some new ones. At the end of the Seder I fully expected someone to question why I was not more actively involved in other observances since I was obviously knowledgeable about them. I was surprised and pleased that no one did. Chavura members welcomed our participation and included us in their community. We were glad to belong.

After returning from Florida, we joined a Chavura where we lived, and later when we moved to Bergen County, NJ, we joined another Chavura there. When the son of Chavura members celebrated his Bar Mitzvah, we were invited to the service. It was held in a very small Conservative synagogue in Ridgefield Park, NJ. I was attracted by the intimacy of the group, the informality of the services, and the equal treatment of women. I also liked the congregation’s emphasis on community participation in the services which were led by congregation members rather than a Cantor. I was especially pleased by the fact that the Rabbi rarely delivered a sermon, but instead raised questions about the sections of the Torah being read that week. We joined that congregation and I became an active member and frequently led services.

Eventually, we joined other synagogues with similar characteristics, and we have now belong to two congregations. One is a non-denominational synagogue In Chatham Center NY, half an hour’s drive away from our home in the Berkshires. We are also members of Knesset Israel (KI), a Conservative egalitarian synagogue in Pittsfield, only a few minutes drive from our home. Services at KI are largely participatory and conducted largely in Hebrew, and I have a warm sense of being at home when I join in the traditional melodies and occasionally lead services. I like the fact that members lead all services, including reading from the Torah. KI has a strong sense of community, and a warm and capable young Rabbi who values it, and we are happy to be a part of it.

My wife asked me about the contradiction of being comfortable during services, and actually eager to lead them despite the fact that it is difficult for me to believe in God. I told her that when I mentioned God at services, I think of the history and especially the values of the Jewish people. I cherish values such as charity, honoring learning and education, and caring for those in need, whether they are sick, weak, young, or old. It is not an accident that virtually every major city in the world has a Jewish hospital, a Jewish old age home, and frequently a Jewish school. For me mentioning God during services stands for being part of the Jewish community that honors these values. It also means feeling connected with my ancestors and with succeeding generations of my people. Finally, while participating in services I identify with the Jewish people and the persecution they suffered throughout history. At those times I also continue to commit myself to doing what I can to assure that such persecution would not again befall Jews, or other minorities persecuted by uncaring, cruel majorities.

Connection to a community becomes important in the face of the sometimes terrifying twists of an apparently random fate. My memoir describes how our family ended up in Shanghai during the Second World War. After Kristallnacht, my parents decided to make their way to Antwerp, then an apparently safer place for Jews than Germany. Since my father was Stateless, he could not obtain a visa and was smuggled across the border and picked up by a Belgian patrol. The Belgians turned him over to German authorities, who imprisoned him in the Dachau concentration camp Before World War II discharge from Dachau was possible if those imprisoned could leave Germany, setting into motion our flight to Shanghai. Little did we realize then that my father’s ending up in Dachau saved our lives. Ninety percent of Belgium’s Jews perished in the Holocaust, and that would surely have been our fate had my father succeeded in getting to Antwerp.

Observant friends attribute our survival in China to the will of an omnipotent God. When asked how such a God can idly sit by while one and a half million Jewish children under sixteen, among the six million other Jews, were slaughtered during the Holocaust, these believers take refuge in the thought that mere humans can not fathom the awesome plans of the Almighty, or other explanations that sound inadequate to my ears. For me, close ties to family, friends, and a caring community are greater consolations against the randomness of fate, which mocks even the most carefully made plans, than a remote, apparently uncaring divinity.

During services, I prefer to read the selections in Hebrew rather than English, even though I understand perhaps only a little over half of the words. I find myself rushing through the silent sections of the Hebrew service and waiting to participate actively in the parts of the service chanted by the congregation. The chanting gives me an emotional connection to the community missing when the service switches to English. I wonder whether that is because so much of the service is filled with language extolling the awesomeness and omnipotence of the Almighty. The numerous repetitions extolling the supremacy of God probably helped Jews throughout history cope with their feelings of fear and helplessness in the face of persecution. Of course, emphasizing the awesomeness of the Almighty also frightens Jews to increase their observance of the faith.

My feelings about services in the non-denominational Chatham synagogue we belong to are a little different. Even though they have a consulting Rabbi, who leads high holiday services and comes in another half dozen times during the year, that congregation is led largely by the members. A good part of the service is read in English, in addition to the communal chanting which takes up much of the Hebrew sections of the service. However, the English segments tend to emphasize historical milestones of the Jewish people, our shared values, and the beauty of the universe, the stars, the sky, and the oceans- rather than the awesomeness of the Almighty. In this synagogue, rather than reading from the Torah in Hebrew, the section of the Torah read in Synagogues that week is read and discussed in English. The major part of the service is taken up by these wonderful discussions, often lasting well over an hour, that examine the text from historical, philosophical, literary, and psychological perspectives, in addition to religious ones.

The constant glorification of the awesomeness of the divinity during services reminds me of a conversation with the wife of a very observant Orthodox friend. This woman knew that I had studied in the Mirrer Yeshiva, and was knowledgeable about Jewish customs and observances. She could not understand that I now no longer observed most of the laws, whether they dealt with Sabbath observances, our diet, or most others. One day she asked me “Aren’t you afraid of being punished?” I simply answered “No.” She could not have understood my actual answer, that fear of punishment was a terrible reason for believing in God.

*****

Sigmund Tobias, Distinguished Research Scientist, Institute for Urban and Minority Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, is author of Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in Wartime Shanghai