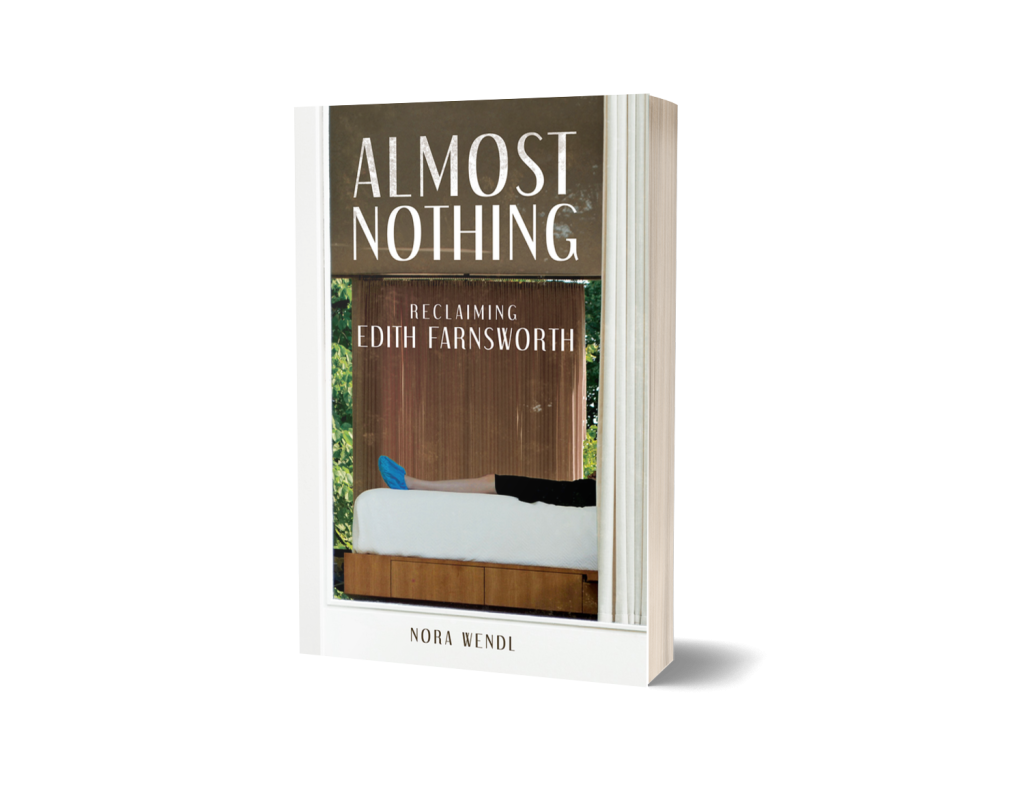

Nora Wendl, author of Almost Nothing: Reclaiming Edith Farnsworth, answers questions about her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I decided to write this book because I wanted to see if it might be possible to write an interior history of architecture—a history of what it means to desire a house, to build a different way of living, which is what Dr. Edith Farnsworth did in commissioning her glass house from Mies van der Rohe. Many histories focus on the building itself, but I have always been fascinated with her, and knew that there was much more about her than met the eye. I also wanted to write for a general audience to understand what it is like to try to change an architectural history (or any history)—what it requires from the author, who becomes implicated in that journey, which is often difficult, especially if you are challenging a status quo.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

Finding out that Edith Farnsworth had written hundreds of poems in her life and had been trying to publish an entire book of them (but was unsuccessful) was surprising to me, and very interesting. I knew she was an accomplished physician, researcher, and had published respected English translations of Nobel Prize winning poet Eugenio Montale’s work and had published a few of her own poems, but seeing that she had her own book-in-progress amazed me. And, that she’d dedicated a poem to M.G.P., Polly Porter, a woman she’d known for decades, was also surprising and revealed in more depth her relationships to women in her life.

The fact that these poems were in an archive held by her former employer, Northwestern Hospital Archives—was a huge surprise. I only “discovered” these because the archivist there, Sue Sacharski, reached out to tell me she thought I’d like to see them. Writers really do rely on the generosity of archives, and the people that run them, I’m very grateful to Sue.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope that this book gives people the space to see histories can be rewritten, that even a canonical historical account of a place or of a past is worth questioning and researching and rewriting—and that the journey of researching and rewriting is worth undertaking, no matter how long it takes. And that it is its own adventure.

I hope that readers will take away the idea that our everyday lives are worth writing about, are themselves the material and texture of history.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

I loved getting reader comments, and then taking their advice to make edits that strengthened the book. Their recommendations were really smart and generous, and it gave me a chance to see the book through others’ eyes—people who had never read it before that moment. Having written the book for many years, it was a welcome perspective, and it gave me butterflies in my stomach: suddenly, the book was something for other people to read. While this might sound obvious, it was really a transformative moment for me: it made me even more excited to get my book in to other people’s hands in the coming months.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

To physically put yourself into your research: I found that my best writing came out of my immediate, physical confrontation with the artifacts, archives, and places that were a part of my research. That finding a source online and viewing a PDF really wasn’t enough: there was something to be learned about confronting the process to actually hold that document or image in my hands that would teach me something, too. I think we forget that archives are not in any way neutral spaces, that accessing them is its own fraught process, and engaging in that process opens up whole new horizons of experience that need to be written into a book, too.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

At the moment, I am really loving contemporary memoirs, and recently have read some remarkable ones: Time is a thing the body moves through, by T. Fleischmann, Voice of the Fish, by Lars Horn, Intervals, by Marianne Booker, and Rehearsals for Dying, by Ariel Gore are recent favorites: there’s nothing like curling up with a fantastic book. I find it much easier to read now that I’ve finished this book and am in the beginning phase of writing the next one, I feel more open and impressionable, and curious about other forms of writing and voices.

Nora Wendl is an essayist, artist, and associate professor of architecture at the University of New Mexico.