Shelton Stromquist and James R. Barrett, the editors of A David Montgomery Reader: Essays on Capitalism and Worker Resistance, answers questions on their new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

We believe David Montgomery’s pioneering work in the field of labor history remains eminently relevant to the field today. New generations of historians and labor activists deserve ready access to this pathbreaking work. His essays, in addition to his books, reveal the breadth and originality of his work that shaped and gave direction to the field at crucial junctures. A consideration of Montgomery’s work allows a view of the field’s trajectory over the past fifty years. His focus on the shifting contours of class relations, the peculiarities of class formation in the American context, the defining impact of the struggle over workers’ control of production, and the racial and gendered diversity of working-class experience have particular relevance today. Montgomery understood—from his own shop-floor experience and from his scholarship—the ebb and flow of workers’ self-activity and the power and the inventiveness of capitalism. In this period of renewed rank and file activism across new as well as older sectors of the economy, his historical rendering of working-class organization and activity has particular salience.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

We examined some of his unpublished writing from different stages of his career and discovered that by integrating a few of those pieces with his published essays, new and more subtle insights into his evolving ideas were possible. Considering the unpublished work in relation to the published essays often allowed us to see the evolution of key ideas. For example, while still in England in 1968, teaching with E.P. Thompson at Warwick University and through encounters with the militant British shop stewards’ movement, he drafted an early essay on the political implications of skilled workers’ struggle for shop floor control. This unpublished paper, delivered at a small conference after his return to the US, foreshadowed in interesting ways his major published work on “workers’ control”, which became one of his lasting influences on the field.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

Montgomery’s contributions to the field are often understood to have been related to his emphasis on “class” as an analytical category and the workplace as a site of class formation. While this in many respects is accurate, what is sometimes neglected is the extent to which, especially in his essays, he drew attention to the diversity of working-class life outside the workplace—in social relations, politics, and in family and community life. For him class and workers’ self-activity were inseparable from a richly documented understanding of the day-to-day fabric of working-class life. His essays show a deepening understanding of the interplay of race, gender, and ethnicity with the processes of class formation in both the workplace and beyond.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most challenging?

The challenges of this project were both conceptual and technical. Identifying and selecting a finite set of essays from the large body of published work of our mentor, who is no longer available to guide these choices, was a challenge. Like many of us, Montgomery also produced a large body of unpublished writing, in addition to his published work, that resides in the archive of his personal and professional papers. One of the challenges was selecting and then conceptualizing how to integrate a few of the most important unpublished pieces within the body of his published work.

The technical challenge of producing a digitized manuscript from the original published essays or manuscript texts proved significant. It required reformatting and multiple reviews of scanned text to produce editable digitized text.

The most interesting part of the process for us intellectually was revisiting all this work, thinking anew about the originality and importance of the essays, and jointly crafting an introduction and headnotes that would guide the reader into the essays.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

Don’t underestimate the work of producing an edited volume at each step of the process—gathering and selecting the essays, securing permissions, acquiring appropriate photographs (with permissions to publish), drafting interpretive sections of the volume, reviewing and editing the texts before and after copy-editing, and producing and editing a comprehensive index. Collaborative editing enriches the process but also adds layers of absolutely vital communication.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

For Barrett: “Work music” – always in the background – is usually classical, especially Russian, Eastern European, and American composers, but I also enjoy traditional Irish and American music and the Blues. I would like to be reading more fiction, but when I do read it, it is usually contemporary American and Irish novels. I watch historical documentaries and too many British detective shows.

For Stromquist: I enjoy a wide range of music, with special affection for baroque, classical jazz, and folk. I’ve played some folk guitar (same few chords forever) and enjoy singing social movement and labor songs with small groups of friends, very occasionally and with some trepidation in public. I can’t seem to stay away from history and non-fiction in my general reading for pleasure—favored topics recently have been the rise of fascism in Europe and the Spanish Civil War. I do venture into some fiction, but usually of a historical variety—lately Isabel Allende (A Long Petal of the Sea), James McBride (The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store), and a return to Ernest Hemingway (For Whom the Bell Tolls).

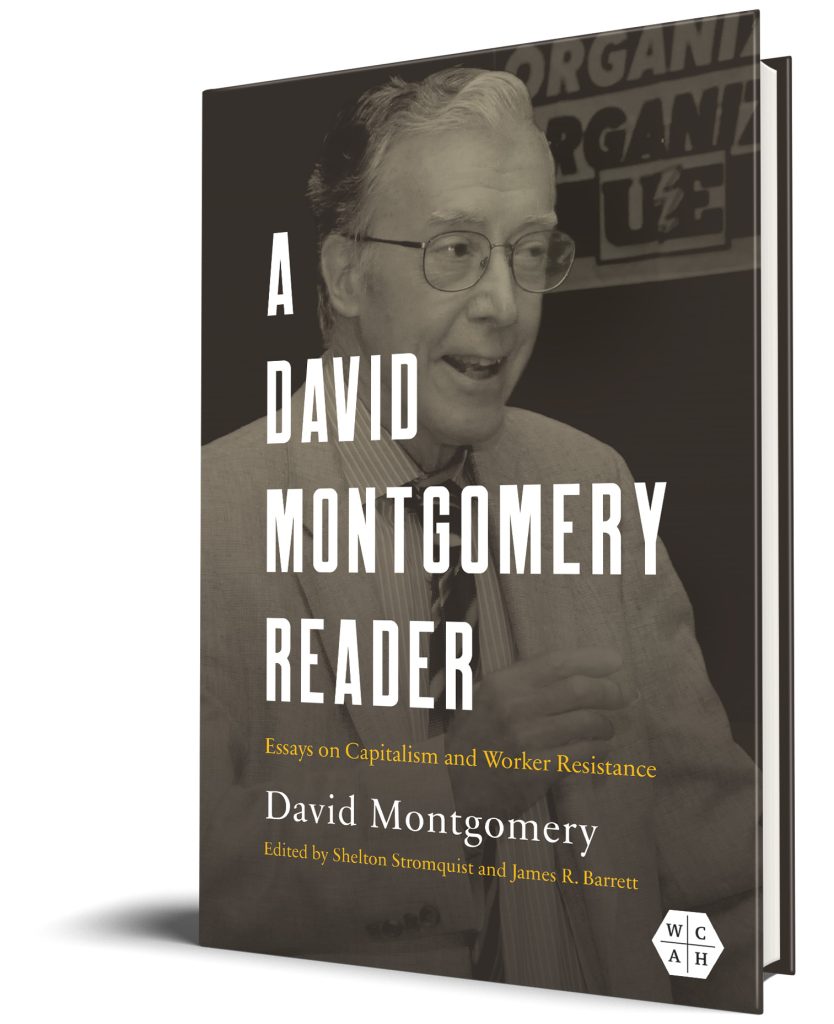

David Montgomery (1927–2011) was the Farnam Professor of History at Yale University. His books include The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925.

Shelton Stromquist is an emeritus professor of history at the University of Iowa and a past president of the Labor and Working-Class History Association. He is the author of Claiming the City: A Global History of Workers’ Fight for Municipal Socialism.

James R. Barrett is an emeritus professor of history at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Scholar in Residence at The Newberry Library. He is the author of History from the Bottom Up and the Inside Out: Ethnicity, Race, and Identity in Working-Class History.