The tragic death of 29 miners at West Virginia’s Upper Big Branch mine on April 5th, along with President Obama’s call for better federal oversight over mine safety, should remind us that the struggle to establish effective government regulation over working conditions has persisted through modern American industrial history. One troubling aspect of the Upper Big Branch disaster is that it took place fully under the gaze of the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) founded in 1977 and strengthened after the Sago mine disaster in 2006. MSHA inspectors have been citing Upper Big Branch’s operator, Massey Energy, for serious safety violations for years, but Massey has tied up most citations in the regulatory appeals process and kept Upper Big Branch open and operating, accident risks and all. One wonders what it takes to make regulation effective.

The tragic death of 29 miners at West Virginia’s Upper Big Branch mine on April 5th, along with President Obama’s call for better federal oversight over mine safety, should remind us that the struggle to establish effective government regulation over working conditions has persisted through modern American industrial history. One troubling aspect of the Upper Big Branch disaster is that it took place fully under the gaze of the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) founded in 1977 and strengthened after the Sago mine disaster in 2006. MSHA inspectors have been citing Upper Big Branch’s operator, Massey Energy, for serious safety violations for years, but Massey has tied up most citations in the regulatory appeals process and kept Upper Big Branch open and operating, accident risks and all. One wonders what it takes to make regulation effective.

Critics of the Upper Big Branch incident, President Obama included, have advocated strengthening MSHA with administrators more dedicated to protecting workers than serving business, and with enhanced powers to impose tougher sanctions on negligent firms allegedly like Massey. The assumption is that a more powerful federal agency will improve regulatory results.

My own study of state regulation during the Progressive era, Making Capitalism Safe: Work Safety and Health Regulation in America, 1880-1940, suggests that more comprehensive regulatory methods might be more effective. Progressive reformers that I examined set up a patchwork of state safety-and-health plans, among them several intriguing commissions in Wisconsin, California, and Ohio that moved beyond blunt application of governmental force with programs that aimed to reshape the economic and ideological environment in which manufacturers operated. Carefully rigged workers’ compensation insurance incentives, safety codes jointly formulated by workers, employers and experts, robust state-sponsored safety education, and instructional factory inspection all supposedly worked together to create a milieu that made safety profitable for employers and part of their business philosophies.

Such state programs certainly had their weaknesses, but their broad systematic approach to regulation might offer lessons for those nowadays who endeavor to reform regulatory apparatus and prevent any more calamities like those at Upper Big Branch.

*****

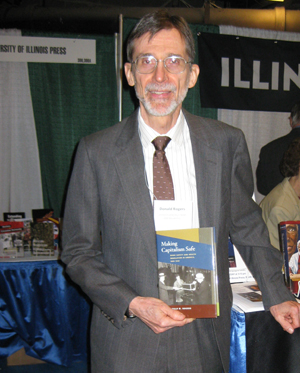

Donald Rogers is a history instructor at Central Connecticut State University and Housatonic Community College, and author of Making Capitalism Safe:

Work Safety and Health Regulation in America, 1880-1940.