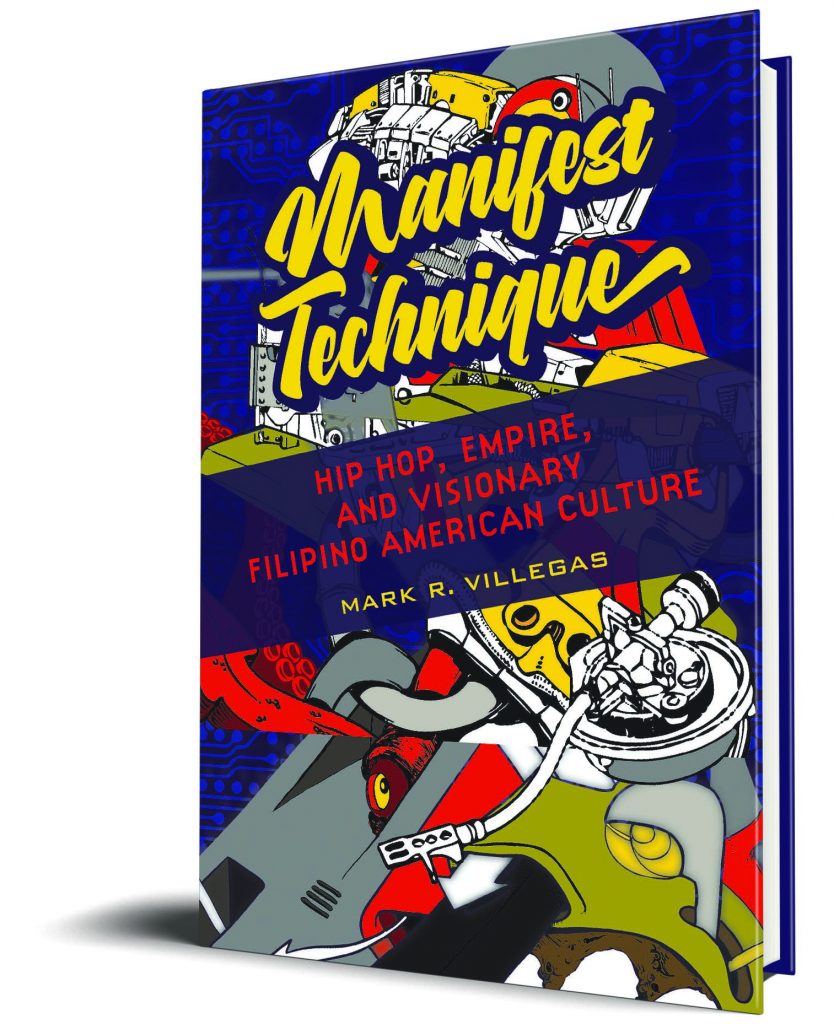

Mark R. Villegas, author of Manifest Technique: Hip Hop, Empire, and Visionary Filipino American Culture, answers questions on his childhood influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways in his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

This book was inspired by my own experiences as a second-generation Filipino American. Growing up on and near navy bases in the 1980s and 1990s meant growing up in a large, concentrated Filipino American community. I mention in my book that some student clubs in my high school (such as the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) in Jacksonville, Florida were largely Filipino American clubs. Filipino kids were always at the forefront of hip hop cultural innovation in dance, music, fashion, and graphic arts. People didn’t become famous or make money from it; more importantly, they built community while fortifying cross-racial collaborations. To me, these interrelated phenomena were common sense. But when I got to college, it became clear that people generally didn’t know much about Filipinos. We are among the largest populations in certain metropolitan regions, yet we remain difficult to pin down or are completely obscured. I wrote this book as a small effort to better understand the dynamics and multiplicities of Filipino American culture. Manifest Technique is an exploration of militarism, spirituality, fantastical imaginations, and dance embodiments among Filipino Americans. I argue that Filipino Americans’ cultural productions in hip hop perform critical memory work and provide complex political critiques. Hip hop and even pre-hip hop (e.g. jazz, funk, disco, R&B, and soul) are precious for several generations of Filipino American cultural vernaculars.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

My biggest influences were the dancers, DJs, and graphic artists of my childhood. I lived in Long Beach, California during the height of gang activity in that region. I remember we couldn’t wear certain colors or shoe brands because we could get “checked” by so-called gang members. This was in elementary school, mind you! But interwoven within the hysteria around gangs was the blossoming of a new wave of hip hop culture in Southern California. Filipino Americans were not just participants in this wave, they were respected innovators and leaders. We had top DJs, graffiti writers, and dancers. We had crews, mirroring and overlapping with gang culture. I remember my oldest brother, Thom, and his crew getting down at house parties. Filipino “houzers,” stylish with their wild hair, colorful shirts, and big jeans, fused breaking and house dancing into their moves. Houzers were a solid part of my early childhood; my mom recalls cooking giant spreads for these houzers and other partiers at our navy housing home. For me, hip hop was encoded into the DNA of Filipino American culture. The music, dance, DJs, tagging, fashion, lingo, and even spiritual philosophies influenced my thinking and research questions for this book.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

When I was younger, I assumed all Filipinos in the U.S. were associated with the navy. Whenever I met Filipinos with no navy connection, I would think they were weird. Every navy brat carried a gray military ID card to gain access to the base, grocery store, gym, and so on. So, to me, ID-deficient Filipino kids were strange! This cognitive dissonance was particularly acute when I escaped to college. I slowly learned to detach the navy from Filipinos in order to appreciate the fuller, more beautiful scope of Filipinoness. However, once I started interviewing people for my research, I encountered a disproportionate number of Filipino American artists with navy ties. This wasn’t a “discovery,” but more of an affirmation of what I had already understood: hip hop and the military had intertwined histories. I had no choice but to dedicate a book chapter on the migration of hip hop along military routes. Even after writing the chapter, I still gasp “no way!” when artists reveal to me their military backgrounds.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

A popular myth is that Filipino Americans are outsiders doing something different from “real” hip hop. This is why I don’t use the term “Filipino American hip hop” as this phrase implies a separate genre (maybe hip hop music in a Filipino language). While it is true that some Filipino American artists make music with a sprinkling of Filipino words and paint murals with references to Philippine mythology, the larger story is that Filipino Americans have always been collaborators in broader hip hop communities. These communities have been maintaining and creating hip hop culture together. Filipino American hip hop performers, artists, audiences, and practitioners were prominent in very early multiracial hip hop scenes. While not the main point, my book suggests the historical significance of Filipino Americans in hip hop. I show that Filipino Americans are not outsiders: because of the powerful influences of U.S. colonization, they have always been intimate collaborators in a variety of Black popular expressions throughout the 20th century and beyond. Filipino Americans adapted their skills of West Coast boogaloo and popping (local Black dance styles that predate New York hip hop) to become among the best breakers, houzers, and hip hop dancers. The same pioneering spirit applied to the DJ scene. For example, DJ Nasty Nes started the first West Coast all-hip hop radio show in 1980 in Seattle. Filipino Americans also led a thriving freestyle music and R&B scene in the San Francisco Bay Area during the late 1990s.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

Colonization changes culture in unexpected but significant ways. I hope readers appreciate that Filipinos have a funky history and an even funkier culture.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I read a lot of Filipino American fiction, which is in a moment of renaissance right now. Most recently, I completed Arsenic and Adobo (Mia Manansala), Insurrecto (Gina Apostol), America is Not the Heart (Elaine Castillo), In the Country (Mia Alvar),and the memoir The Body Papers (Grace Talusan). I have been watching Netflix anime and horror; I finished the Trese series, the first anime based in the Philippines and made by Filipinos and Filipino Americans. All I listen to is 1990s R&B music, honestly. Just play me some SWV, Aaliyah, Total, Monica, Brandy, Usher, Tamia, Faith Evans, Keith Sweat, Tevin Campbell, Tony! Toni! Toné! and Blackstreet.