The first chapter of my new book, The Myth of Manliness in Irish National Culture, 1880-1922, re-imagines the political legend and legacy of Charles Stewart Parnell, the great late-Victorian Irish leader, brought down by a sex scandal at the zenith of his career. Although my Bram Stoker/Dracula book (UIP, 2002) was then on the front burner at the time, I had already begun research into the gender performance at work in Parnell’s leadership when Bill Clinton’s “Lewinsky scandal” broke in January 1998. It was impossible not to see the connection between the fates—one sealed, one in prospect—of the two politicians, not least because the long awaited Northern Ireland truce–what would come to be known as the Good Friday Agreement–was coming to fruition at the same time. Parnell became famous for engineering a “Union of Hearts” between the long antagonistic Irish and British nations; Clinton stood on the verge of a seemingly impossible achievement in brokering an end to the Anglo/Irish “Troubles”; and both, at the moment of their strikingly similar triumphs, were struck down by the same combination of sexual dalliance and social disapproval.

The first chapter of my new book, The Myth of Manliness in Irish National Culture, 1880-1922, re-imagines the political legend and legacy of Charles Stewart Parnell, the great late-Victorian Irish leader, brought down by a sex scandal at the zenith of his career. Although my Bram Stoker/Dracula book (UIP, 2002) was then on the front burner at the time, I had already begun research into the gender performance at work in Parnell’s leadership when Bill Clinton’s “Lewinsky scandal” broke in January 1998. It was impossible not to see the connection between the fates—one sealed, one in prospect—of the two politicians, not least because the long awaited Northern Ireland truce–what would come to be known as the Good Friday Agreement–was coming to fruition at the same time. Parnell became famous for engineering a “Union of Hearts” between the long antagonistic Irish and British nations; Clinton stood on the verge of a seemingly impossible achievement in brokering an end to the Anglo/Irish “Troubles”; and both, at the moment of their strikingly similar triumphs, were struck down by the same combination of sexual dalliance and social disapproval.

I spoke with my late father (a fiercely moral man, to whom this book is dedicated) about Clinton’s woes at the time, and his response was one of disgust without surprise: it was the kind of thing, he suggested, that we always assumed without being able to know for sure. In this respect, Clinton’s image in disgrace was not the likeness but the obverse of Parnell’s: everybody who was anybody knew perfectly well of Parnell’s romantic arrangement, but no one would assume it into evidence, would presume to acknowledge its reality, would turn open secret into established fact. And so whereas the Clinton scandal managed to titillate without shocking the public, the Parnell scandal shocked deeply and titillated hardly at all. Talking with my father, it struck me that this reversal from one case to the other was bound up with the moral and political concept of manliness that I had set out to explore. You see, the late Victorian idea of manliness proceeded from a certain knowledge that men were beasts at bottom, animated by the rudest, most primitive energies; but it proceeded under the assumption that these same energies could readily be turned against themselves to supply a uniquely effective force of self-regulation.

For better and worse, Parnell was an exemplary specimen of such manliness. To say that Bill Clinton was decidedly not is rather beside the point. At the end of the twentieth century, unlike the end of the nineteenth, manliness in its moral aspect no longer represented the dominant frame of reference through which any politician (as opposed to a soldier or athlete, for example) would be regarded. Our guiding assumption is rather that the distance between a leader’s baser desires or proclivities and his public profile is less a space of self-regulation than of disguise and hypocrisy and, as such, exists precisely to be abridged—on the internet, in the tabloids, or even in legal proceedings. If Parnell shocked his contemporaries, it was because he gave them what they knew but did not expect–not just of him, but of any man. If Clinton did not shock his contemporaries, it was because he gave us just what we have come to expect–not just of him, but of every man. From Parnell to Clinton, history would seem to have repeated itself in the manner Karl Marx observed, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. But this change of genre has less to do with the nature of the respective scandals and their protagonists than with the view their respective public audiences held of the nature of man, or at least men.

*****

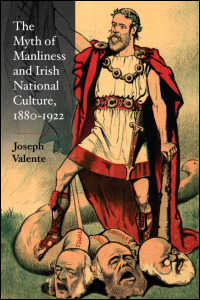

Joseph Valente, a professor of English at the University at Buffalo, is the author of the new book The Myth of Manliness in Irish National Culture, 1880-1922.