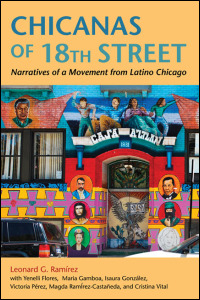

Leonard G. Ramirez’s new book, Chicanas of 18th Street: Narratives of a Movement from Latino Chicago, with contributions by Yenelli Flores, María Gamboa, Isaura González, Victoria Pérez, Magda Ramírez-Castañeda, and Cristina Vital, recently landed on my desk. The official publication date is October 17, 2011, but we will begin shipping back orders over the next two weeks.

Leonard G. Ramirez’s new book, Chicanas of 18th Street: Narratives of a Movement from Latino Chicago, with contributions by Yenelli Flores, María Gamboa, Isaura González, Victoria Pérez, Magda Ramírez-Castañeda, and Cristina Vital, recently landed on my desk. The official publication date is October 17, 2011, but we will begin shipping back orders over the next two weeks.

In Chicanas of 18th Street, six female community activists who have lived and worked in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago discuss how education, immigration, religion, identity, and acculturation affected the Chicano movement.

From the Introduction:

Urban renewal changed the configuration of the Near West Side. Several neighborhoods were upended in order to accommodate an expressway interchange and establish a permanent site for the Chicago campus of the University of Illinois. The evisceration of the Near West Side Mexican community prompted many Mexicans to settle in Pilsen, another traditional imimigrant port of entry, just south of the Hull-House area. In the 1960s, Pilsen became the first predominantly Mexican community in the city (Kerr, 1976) .Concentration of the Mexican population facilitated Mexican community development.

The changing character of Pilsen allowed Mexicans to have some impact on local community institutions. Churches began to adjust to the influx of Mexicans. Masses were offered in Spanish, special outreach programs were developed for Mexican families, and churches became vibrant community centers that involved entire families. Although Mexicans certainly influenced the local schools, the relationship between the Mexican community and the Chicago Public Schools was problematic. Issues such as bilingual education, the hiring of Mexican teachers, inadequate facilities, and the general poor quality of education became points of tension and eventually open opposition.Mexicans were soon able to exert their influence through the neighborhood civic organizations. Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, originally serving a Bohemian population, eventually became a vehicle for Mexican civic action. Developed as an Alinsky initiative, Pilsen Neighbors became a center for community grassroots leadership.

In the 1960s, economic and political systems were being challenged at every turn. Across the Third World, those nations conquered and exploited by Europe and the United States, such as Vietnam, were demanding independence. Popular forces in developing countries were rebelling against neocolonial exploitation (Galeano, 1973). Armed rebellion against authoritarian regimes linked to foreign interests was commonplace. The Cuban Revolution proceeded on a left trajectory and defeated the United States at the Bay of Pigs. Revolution was in the air, and it was reaching the United States (Elbaum, 2006; Gitlin, 1993; Pulido, 2006).

In the United States, Blacks tired of economic, political, and educational marginalization and gradualist remedies that amounted to little progress entered a community process to secure civil rights that soon transitioned into a call by some for Black power and fundamental structural change. The Black civil rights struggle and the antiwar movement ignited other campaigns for social justice, including women’s and gay rights movements. Subordinated groups that historically had been exploited and relegated to the bottom of the social and gender hierarchies joined the appeal to democratize the nation, seeking full citizenship rights either within the constraints of the current political system or as a product of the reconfiguration of another. Mexicans had a long history of resistance in the face of adversity. Political strategies such as those advocated by the League of Latin American Citizens and the GI Forum, organizations that had developed in the face of great adversity in the 1920s and 1940s, attempted to exchange patriotic loyalty and military service for the prerogatives of full citizenship. However, segments of the Vietnam generation tired of this strategy that seemed to yield few results. Despite being loyal constituents of the Democratic Party, the needs of Mexicans continued to be ignored (G. Mariscal, 2005; Navarro, 2000; Oropeza, 2005).