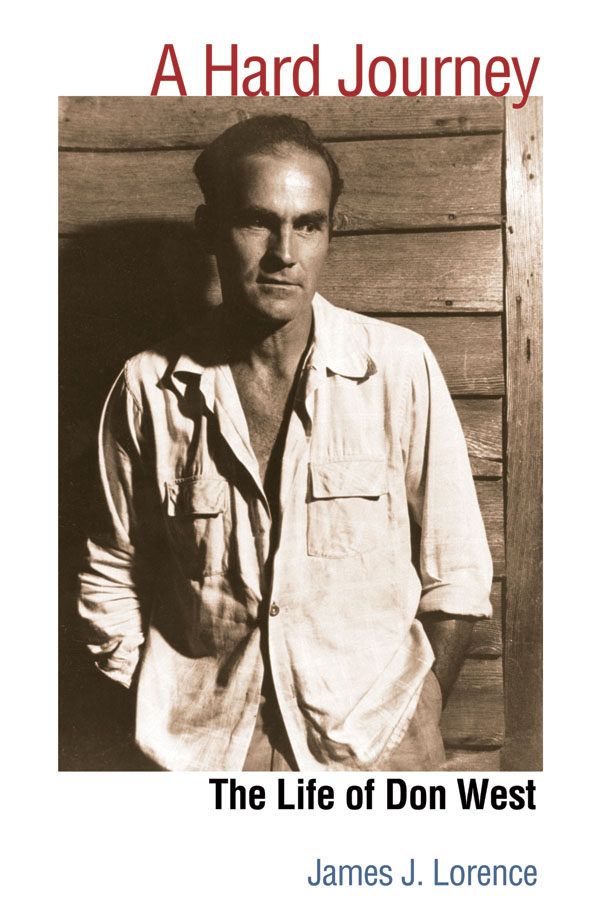

Jeff Biggers is the author of In the Sierra Madre (University of Illinois Press, 2007) and The United States of Appalachia (Shoemaker and Hoard, 2007). The University of Illinois Press recently published James J. Lorence’s A Hard Journey: The Life of Don West.

I first met Don West in the early summer of 1983. I was a dropout from the University of California and had just gone through a wild nine-month tour of duty in Berkeley’s corridors, spending more time in jail and at leftist political meetings than in classrooms. I failed to finish my last quarter.

Returning from a stint in jail for a demonstration in central California, I was involved in a tragic car accident, which resulted in the death of a young woman. I was at the wheel. Still in a daze, I eventually took a Greyhound across the country, and then started hitching and hiking through the South, drifting into the Appalachian Mountains. I was angry, resentful, and adrift. I had lost faith in the power of education, politics or even activism. Don West saved my life that summer.

Here are his bona fides as I see them: Raised by a sharecropper from the north Georgia mountains, West put himself through Lincoln Memorial and Vanderbilt Universities at the same time the southern Agrarian literary movement took the stage in the late 1920s. But West was no youthful antebellum sycophant; he earned a master’s in divinity, traveled around Scandinavia and Europe to examine folk schools, and returned to the South to launch his own revolution in the mountains. Raised by a radical Republican grandfather in a part of Appalachia that had supported both the Union and Confederacy, West rejected the hillbilly stereotypes for his proper place in the mountain South’s vanguard for independence, freedom, and enlightenment.

In 1932 he co founded the Highlander Folk School, which became the training ground for the civil rights movement. As one of the lonely activists in the generation before the glorious Montgomery bus boycott, he went underground and defended a radical black (Communist) leader in Atlanta in the mid-1930s. Wanted dead or alive by the Atlanta authorities, he fled the state and became a union organizer for mill workers and miners in the Carolinas and Kentucky and was often beaten and jailed, often forced to quietly return to work his farm in Georgia.

Not too quietly: In a top secret FBI file, West was added to a proposed list of dangerous Americans who should be interned during World War II. In fact, one memo referred to the poet as the most dangerous man in the South.

There were some good times. After turning a small Georgia school district into an acclaimed model of transformative pedagogy and cooperative learning, he returned to the national scene with his Clods of Southern Earth. In 1946, New York publishers Boni and Gaer (Boni had published Ernest Hemingway’s first stories) announced the release of West’s record-breaking volume of poetry. Here is where his secret life began to haunt him.

During all of these years, riding an Indian Chief motorcycle across the mountains and down the East Coast, West had left a legacy of poems in his wake, as author John Egerton has written, like a phantom revolutionary—poems that unveiled the miseries of mill hands, miners, and sharecroppers, and the hopes of justice and racial unity in the South. His pioneering work reclaimed Appalachia as a progressive region and purveyor of the good life. For a while, he became the proverbial people’s poet, his work passed out at rallies and memorized by miners who had never read a book in their lives.

Hounded and red-baited by newspaper after newspaper in the late 1940s and 1950s, West drifted into oblivion, losing job after job, called time and again into the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearings that popped up in the South with the regularity of catfish fries. In one of the most unusual persecutions in American literary history, West’s poetry was often used against him at hearings and in newspaper editorials. Destitute, he even took to peddling vegetables from his garden on the streets of Atlanta. The Ku Klux Klan added a final touch, burning down his farm and his collection of books, manuscripts, and family heirlooms. After editing a newspaper in a mill town in North Georgia during a volatile period, he even had to flee a lynch mob; scurrying across the back mountain roads, West shot his way out of a jam, when a car attempted to drive him off the road. He finally left the South in exile.

When I was literally dropped on Don West’s doorstep in the 1980s, he had returned to Appalachia as one of the elder statesmen in their folk revival. He had become the link between the Old Left and New Left activists in the 1960s, and had founded a new folk school and farm, the Appalachian South Folklife Center in West Virginia, which had become a hub of activity for young Appalachians in search of their history and progressive culture. His poetry returned to print and sold thousands. His role as an Appalachian historian became more poignant with a series of pamphlets he printed in his barn in the tradition of his hero, Tom Paine.

With less than 10 bucks in my pocket, I worked on West’s farm that summer. I attended classes he set up for school dropouts and mountain youth in an employment program. We listened in awe at West’s poetry readings and his lessons on the heroic role of mountaineers at Kings Mountain during the American Revolution. “Remember,” he would shout, “we had the first abolitionist newspaper, not the northerners,” and then pausing, he would always end, “and we didn’t burn any witches in these hollows.”

Don was passionate, unyielding, purposeful. He was also challenging.