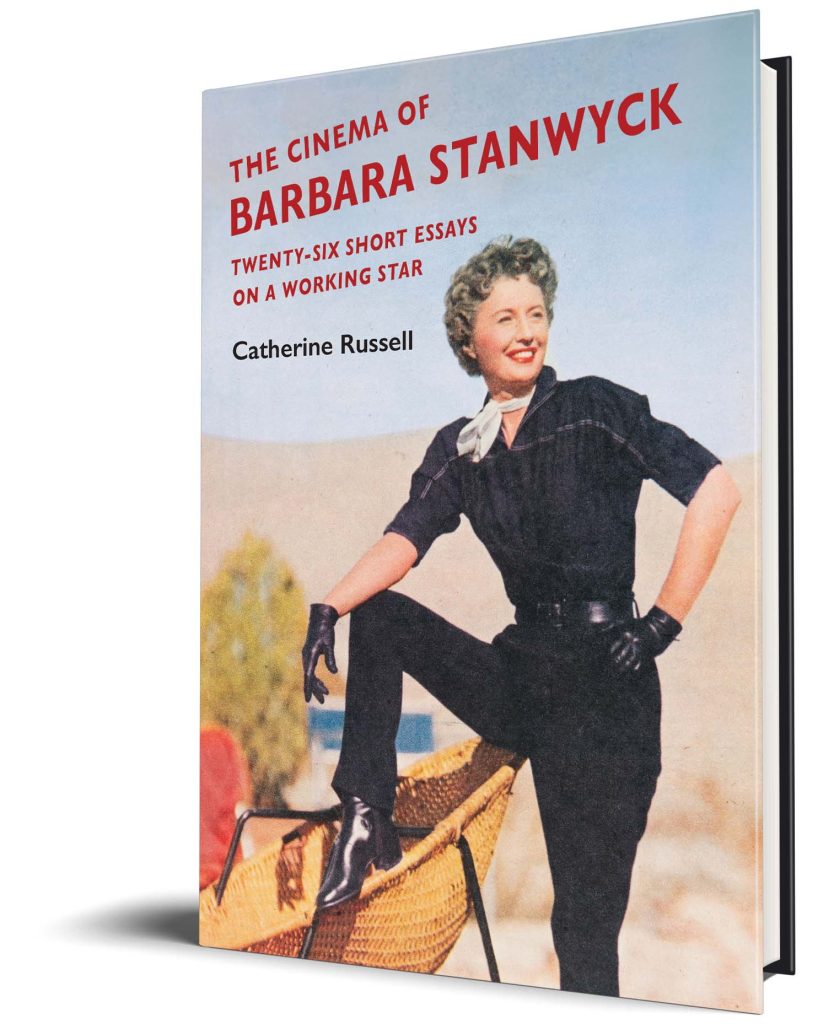

Catherine Russell, author of The Cinema of Barbara Stanwyck: Twenty-Six Short Essays on a Working Star, answers questions on her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I wanted to write about Hollywood cinema of the classical period from the perspective of a woman whose career extended through many years and genres of the American studio system. Most histories of Hollywood are centered around great directors, or the studios, or different genres in which women are sidelined as stars or divas, or romantic weepers. Barbara Stanwyck, like many women working in Hollywood, was a hard-working member of the industry whose screen presence and personality as a tough, versatile, and talented woman constituted a valuable contribution to what we call Hollywood cinema. Moreover, as a star, her brand continues to “sell” Hollywood films in the form of DVDs and retrospectives in theatres and streaming services.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I found that writing women’s history has challenges and opportunities that I had not expected. This is an emergent field of film studies, as scholars are developing new methods of research and writing with which to account for women and racialized people who have been sidelined by archival practices. It can be extremely rewarding to work with the fragments of trivia, gossip, popular biography, and marginalia that come to the surface of the archive once you scratch it. I found that my project was in good company, and that the materials that I found, in conjunction with Stanwyck’s hundreds of screen appearances, could produce a unique portrait a cultural worker.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

One myth of the studio system is that stars were owned and managed by the studios, with little agency of their own. Stanwyck’s story is that of a freelance worker who managed to make her way through all the major studios, and to work with many of the top directors of the mid-twentieth century. At the same time, Stanwyck’s agency was limited and she took many roles that are demeaning, or in which her characters are undercut. I found that writing from a feminist perspective, it is possible to call out the misogyny of the industry, and at the same time, recognize the talent, perseverance, and integrity of one of its biggest stars. The fact that Stanwyck was a conservative, homophobic republican does not make her any less of an icon for feminist history and practice. Women’s heroes will not always live up to our expectations of feminist values, but they can be critically significant to women’s history nevertheless.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

I really enjoyed working on the illustrations which I made from frame enlargements from the films that Stanwyck performed in. The ability to use images taken directly from films is a great tool for film studies scholarship, as it enables the author to pull out critical moments, captured in the form of gestures frozen in time. They can really help to illustrate a critical point, help the reader to grasp the sensory qualities of performance, and isolate certain moments that may be typically overlooked while watching a film. Film stills found in archives are usually what the producers want us to take away from a film; they are designed to sell films. Thus, it is important for critics to cut across that discourse by making our own images that foreground what interests us. I worked with a photographer to get the best quality reproductions and I am pleased that I could include so many in this book.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

The research for this book spanned over ten years, and it took a long time for the project to take shape. My advice would be not to let the lack of a plan prevent you from exploring and digging in every direction possible. The abecedary structure turned out to be a wonderful device as it enabled me to open 26 different doors to Stanwyck’s career, and at the same time, it imposes its own limits on the scope of each thematic inquiry. Writing 26 short essays rather than 4 or 5 long chapters was actually fun and it also provided a way of doing history outside the conventions of historical storytelling. I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys writing in experimental ways, using arbitrary parameters to help shape material that is retrieved in fragments.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I watch a lot of movies, including classics of the American cinema, which are being restored and made available on streaming services at an exciting rate. Many films that I have heard about for yeas are finally coming to me in my own home! I also watch recently released movies at local theatres, and at film festivals. And I read novels constantly. I recently discovered the work of Eve Babitz, a Los Angeles-based writer and party girl from the 70s and 80s. Great writing!

Catherine Russell is Distinguished University Research Professor of Cinema at Concordia University. Her books include Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices and Classical Japanese Cinema Revisited.