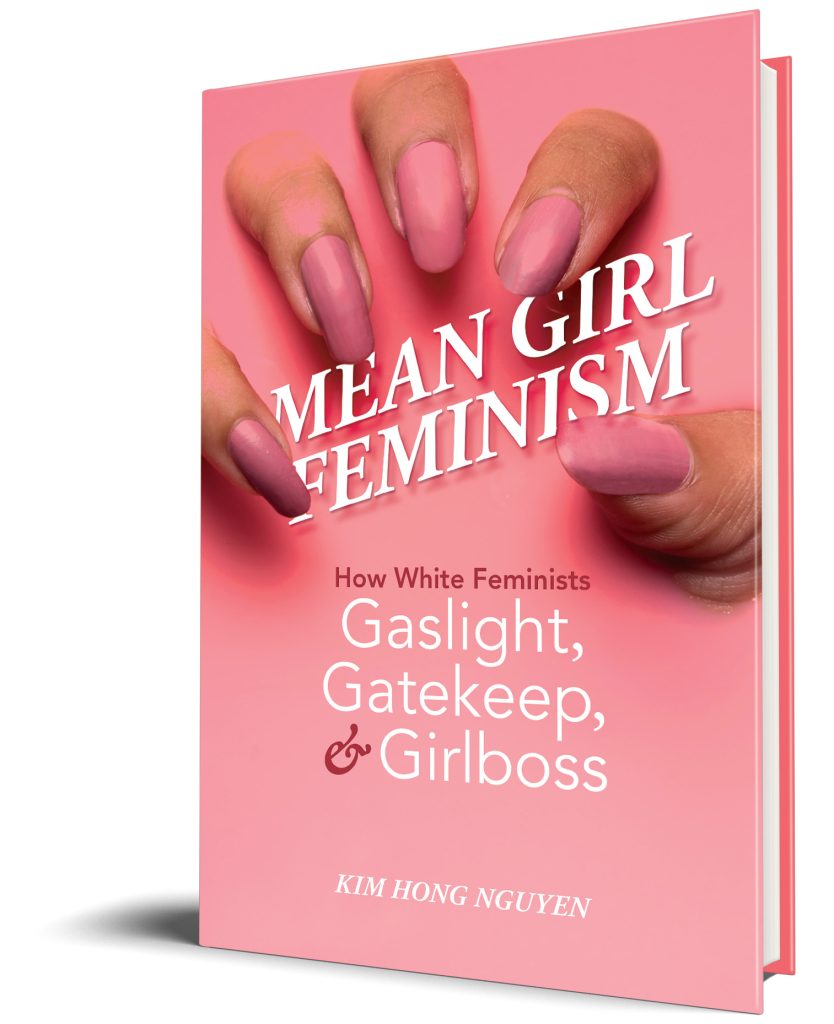

Kim Hong Nguyen, author of Mean Girl Feminism: How White Feminists Gaslight, Gatekeep, and Girlboss, answers questions on her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

Am I a feminist? What feminist wave are we in? Is being nice to other girls and women necessary to feminism? What kind of feminist are you? Is that feminism? Why don’t you call yourself a feminist? Can a feminist wear a skirt? Do I sound like a feminist? This line of questioning is all too common for new students and readers interested in the study of feminist thought. Similarly, gender studies has been preoccupied with this set of questions that revolve around performing a coherent identity of feminism. Instead of combatting gender-based violence and other forms of oppression in everyday life, feminism has become obsessed with the performance of feminist identity. Although white women have long tried to delineate what constitutes the feminine and womanhood in order to leave out Black/brown women and queer/trans folks and the working class and the disabled from their advocacy, white women have continued this line of thinking with a concern over what constitutes feminist performativity.

I wrote in recognition that my academic training promotes a value system that renders white feminism superior, links white feminism to western standards of rationality and reasoning, and posits white feminism as central arbiters of justice and equity. The popularity of feminism coupled with unexamined white rage encourages white women to participate in what I call mean girl feminism, whereby feminism privileges the articulate and the bitchy and sassy in order to continue control the construction of femininity as antipatriarchal resistance. Thus, I also write as a recovering mean girl feminist myself, wanting to resist systems of oppression, but living with the expectation that feminist protest involves being mean assholes. To this end, feminism has lost a sense of where the harm comes from by appropriating the kinds of anger that has been stereotypically associated with racialized women: the snappy Black woman, the cold dragon lady, the loud Latina, the angry Indigenous woman…

Ultimately, I wanted to write this book to share my understanding of how feminism has always been a discourse of whiteness. And I wanted the book to begin and end on the unsatisfactory feeling that I have about feminism: that I may have been a feminist but could not name myself as such because I wasn’t part of the club, or I didn’t have the right language, or I wasn’t sure if I was angry enough, or I was not following the proper lineage and upbringing and doing right in relation to my own mother and other women of color in my life. At the same time, I wanted to write a book that explored key moments of performing white feminism that both contributed to my own marginalization, and at the same time were constructed as ways to overcome my own marginalization.

There are at least two ways of addressing this. One is by sharing personal anecdotes, which I didn’t feel comfortable doing. I play a huge part in my own circumstance and response. A lot of what has happened to me is because of my own personality, my introvertedness, my social awkwardness, my inexperience or what-have-you in addressing or resisting the situation. And people could read those anecdotes and dismiss them as being caused by my idiosyncrasies and being situated as Viet or Asian/American. As an imperfect person who makes mistakes, I wanted to be careful about calling out mean girls individually and I am sympathetic to injury and hurt and struggle, especially when that injury and hurt and struggle prompts people into action and advocacy work. I recognize that to criticize and call attention to this mean girl culture of feminism that I am writing in a space of performative contradiction. So I chose a second route, to write it using rhetorical analysis of mediated texts that I think bear indirect similarity to my own experiences and perhaps better because the texts provide nuancedness to human action. I hope to help others appreciate the importance of approaching intersectionality as the study of how race and gender are mutually constitutive.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I was and am still surprised by the level of gaslighting, gatekeeping, and girlbossing that happens in the academic profession. This happens when my work is rejected because reviewers claim my work is not paying enough homage to feminism. This happens when colleagues believe the white feminist performativity that is discussed in the book is not applicable to real life, to their life. And it happens when white feminists rationalize the harms discussed in this book by weighing them against their progressive positions on other issues. There is a real need to continue the conversation openly.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I think the most important takeaway I want people to have of my book is that white women have always tried to demarcate what is feminine and/or feminist, and at the same time that demarcation is possible through marginalizing others and centering themselves. When feminism claims that anger is vital to feminist performance, we should be careful to see how that marginalizing happens even in that important claim and ask ourselves who can be afford to be angry and risk of social, institutional, and state violence. The odds are not the same for all women.

Kim Hong Nguyen is an associate professor of communication arts at the University of Waterloo and the editor of Rhetoric in Neoliberalism.