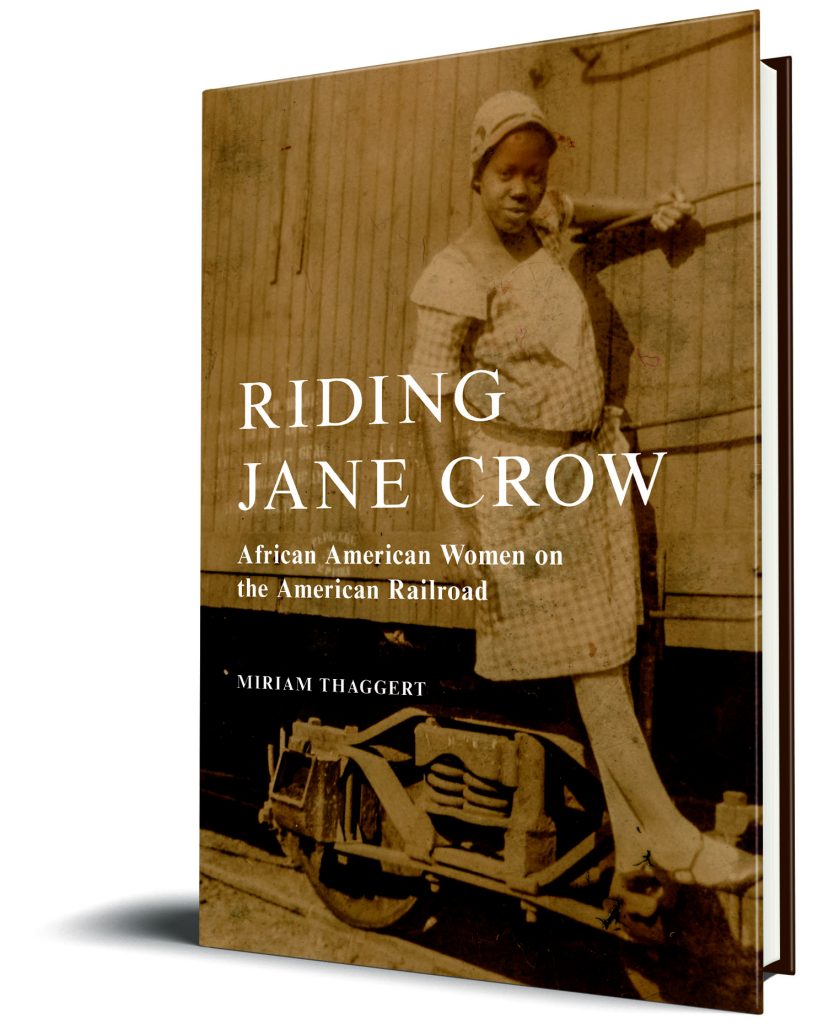

Miriam Thaggert, author of Riding Jane Crow: African American Women on the American Railroad, answers questions on the significance of the time period she writes about, what she hopes readers will take away after reading, and her vision for a curated exhibit.

Q: What is meant by the term “riding Jane Crow” and who coined it?

There are multiple meanings to the term throughout the book. Most readers will be familiar with the phrase “riding Jim Crow,” which means to ride in a segregated space – on a bus or a train, for example. To “ride Jane Crow” is a nod to the fact that I’m talking about the specific experiences of Black female travelers. The term also has a legal meaning. The lawyer, scholar, and poet Pauli Murray used the term to theorize how gender and sexual discrimination are related to, but distinct from, racial discrimination. Murray had a non-conforming gender identity and presented as male when hopping freight cars as a young adult. In the book, I discuss how “Jane Crow,” as used with Murray, has a different resonance, one that signals Murray’s queered form of mobility. So the term takes on different meanings, as you journey through the book.

Q: What is the value of learning how Black women experienced and survived travel on the railroad in the late 19th century, today?

Learning about the travel experiences of Black women in the past encourages us to question what we think we know about mobility and technology of the 19th century and in the present. It helps us realize how so many abstract concepts associated with American national identity, for example “progress,” have, for the most part, overlooked how Black women experienced or figured into those concepts.

The golden age of railroad travel in the late 19th century was also the period of widespread racial discrimination on public transportation. Black women experienced a particularly aggrieved form of racial and gender discrimination when they were forced out of “ladies’ cars.” These were compartments designed with the white middle-class traveling woman in mind. In the book, I talk about how the courtesy white women expected and received as they traveled America’s rails was not something Black women could reliably depend on.

Q: What is significant about 1860-1925 that you wanted to focus your research on that 65-year period?

Within those 65 years, almost the span of a person’s lifetime, we see an important transformation of African Americans, and especially African American women, as political and social subjects. During that time, Black Americans transitioned from enslavement to citizens. The ability to ride first-class unmolested with a first-class ticket on a train is, I argue, one of the ways African Americans tested their citizenship status. Unfortunately, even with three post-Civil War constitutional amendments and an early civil rights act (the Civil Rights Act of 1875), Black Americans were still denied this right. Black clubwomen were traveling often during the late 19th and early 20th century and wrote, publicly and privately, about their difficulties on trains. The year 1925 was the peak period of maids on Pullman cars and the year the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was formed with A. Philip Randolph. Trying to trace the Pullman maid before that year was challenging but quite fascinating

Q: What would you like railroad historians and enthusiasts to take from this book and history?

I would love for historians and train enthusiasts to ask more questions about those groups who have not traditionally been centered in railroad history, in earlier discussions about the train. I hope I will encourage others to ask how marginalized groups encountered different forms of technology and to think about how our national narratives alter when other groups or people are centered.

Q: “Progress occurs when African American women can be identified in an otherwise evanescent archive,” you write. In 2022, how close are we to this as standard practice?

It is an ongoing challenge to broaden and expand the narratives recorded by history. I hope after reading the book that readers will be more attuned to different sources that tell African American women’s stories. There are some stories you will not find in conventional history textbooks. Sometimes the stories are “hiding in plain sight,” so to speak, in letters, diaries, or, as I note with the Pullman maids, in employee cards, the documents used to track their service and interactions with white passengers.

Q: If you could design an exhibition in any museum in the world about Black women passengers and workers, where would that exhibit be and what are some of the artifacts you would hope to find there?

That’s a great question! Most transportation museums focus on the machine, the locomotive, for example. My museum or exhibit would center less on the mechanical and more on the social and personal. I’m curating an exhibition at the Newberry Library in Chicago and that exhibit will tell the story of the Pullman Company maids, who were called at one point in a company magazine, “Handmaidens for travelers.” The exhibit will have employee cards, the instruction pamphlet for the maids and one of the things that really fascinated me, the ID photographs of some of the women who worked as maids. I’m excited to bring the story of the maids out from the Newberry library stacks and into the public, on one of their beautiful first-floor galleries. I’m also thrilled that part of this exhibit will include my leading a seminar on Black travel to Chicago Public School teachers. This feels like a great way to share this neglected part of American history.