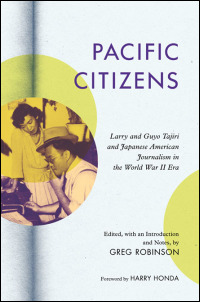

Larry and Guyo Tajiri became leading figures in Nisei political life as the central purveyors of news for and about Japanese Americans during World War II. In the new University of Illinois Press book Pacific Citizens: Larry and Guyo Tajiri and Japanese American Journalism in the World War II Era, Greg Robinson interprets and examines the contributions of the Tajiris through a selection of their writings from before, during, and after the war. He took time to answer our questions about the writing of the book.

Larry and Guyo Tajiri became leading figures in Nisei political life as the central purveyors of news for and about Japanese Americans during World War II. In the new University of Illinois Press book Pacific Citizens: Larry and Guyo Tajiri and Japanese American Journalism in the World War II Era, Greg Robinson interprets and examines the contributions of the Tajiris through a selection of their writings from before, during, and after the war. He took time to answer our questions about the writing of the book.

Q: How did you come to focus on Larry and Guyo Tajiri?

Robinson: When I first started studying Japanese Americans, in the course of research on my first book, By Order of the President, I read through the Japanese American Citizens (JACL) League newspaper Pacific Citizen. I became intrigued by the incisive articles and editorials writen by its wartime editor, Larry Tajiri, and I looked for any information I could find on this mysterious figure. I was surprised to learn that his widow, Guyo Tajiri, was still alive. I boldly wrote to her and asked for an interview. She agreed to meet me, and as we talked, I realized that she too had been a vital player in the production of the Pacific Citizen. I soon got to know Guyo, and we became friends. She warmly encouraged me to study Larry’s career and writings, though she was exceedingly modest about her own. It was Larry’s brother, the celebrated sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri, who invited me on behalf of the Tajiri family to edit a collection of Larry Tajiri’s work, a project to which Guyo gave her immediate blessing. When she died soon afterwards, it became obvious to me that her contributions to Larry Tajiri’s work had to be studied as well.

Q: How did they become leading figures in Nisei political life?

Robinson: Larry Tajiri began working as an editor for the Japanese American press in 1931, at age 17, and within a few years had risen to the post of chief columnist and English-language editor of the San Francisco Nichi Bei, the top community newspaper. In this position, he became a trusted source of information and a real arbiter of taste for the young Nisei. He was also the main organizer of the liberal Nisei “Young Democrat” clubs that formed in the Bay Area. Guyo also was a respected writer and journalist during these years. Once World War II broke out and Japanese Americans were being removed form the West Coast, Larry and Guyo agreed to move to Salt Lake City and together transform the JACL’s little newsletter, the Pacific Citizen, into a fulll-fledged newspaper. As virtually the only sources of outside information for Japanese Americans, they were the leading figures in Nisei political life.

Q: Were they held in the internment camps? Did they have family there?

Robinson: Larry and Guyo Tajiri moved to Salt Lake City, outside of the West Coast excluded zone, just before the deadline for such “voluntary evaucation.” As a result, they were able to avoid behing held in the government camps. However, the families of both spouses were confined in camps, Larry’s in Arizona and Guyo’s in Wyoming.

Q: What problems did the Tajiris run into when publishing Pacific Citizen?

Robinson: As publishers of the Pacific Citizen, the Tajiris faced a daunting set of challenges. Money was extremely scarce. Ninety percent of their client population, the JACL’s prewar supporters, were in official custody. The JACL had further made itself odious to many Nisei by its reluctant decision not to officially opose mass removal. Further, there were forces, both on the West Coast and in Washington, who found it politically attractive to attack both Japanese Americans as disloyal and to propose military custody of all Nisei. Larry Tajiri himself travelled to Washington in order to testify before the Dies Committee (House Un-American Activities Committee) regarding charges of “coddling” of disloyal inmates.

Q: What were some of their most prominent pieces?

Robinson: In addition to writing columns and editorials for the Pacific Citizen, Larry Tajiri wrote in outside journals such as The New Leader, Asia and the Americas, plus a set of columns that he did for the multiracial journal NOW. Probably his signature piece was the article “Farewell to Little Tokyo” he wrote for the pluralist quarterly Common Ground, which dealt with life for Japanese Americans after camp. Guyo did less outside publishing. During the war, her chief contribution was the women’s column she wrote for Pacific Citizen under the name “Ann Nisei.” Her most notable set of writings was undoubtedly her coverage for the Pacific Citizen during 1949 of the trial of Iva Toguri d’Aquino, a Nisei charged with treason as “Tokyo Rose.”

Q: What was the circulation of this publication?

Robinson: Precise circulation figures are hard to come by, especially since copies of the newspaper were handed around among camp inmates, but the best estimate would be something on the order of 10,000 during the war.

Q: How did their roles in journalism change after the war?

Robinson: After Japanese Americans were released from camp, and began starting new locally-based journals or reviving old ones, the Tajiris’ quasimonopoly over the ethnic Japanese press ended. In order both to find a market and to stay relevant, they concentrated on national news, especially questions of civil rights, and hisred correspondents from diverse cities to report on the news there. They also expanded their coverage of sports and entertainment news.