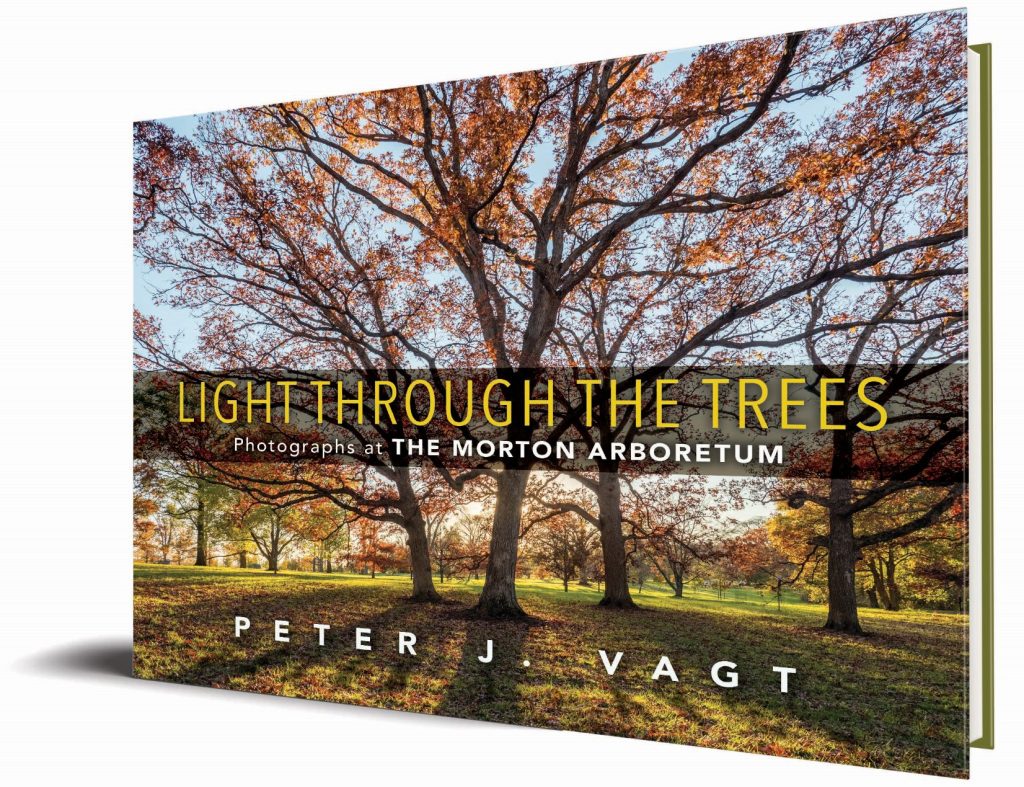

Peter J. Vagt, author of Light Through the Trees: Photographs at The Morton Arboretum, answers questions on his biggest influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I always want to be outside, walking among trees. It’s my favorite thing to do. And when I’m in nature, I love to take pictures and find pictures that show the magic I feel when walking outdoors near and among trees. Twenty-two years ago, I decided to focus on a sole-location project, to take a series of photographs of one location near where I live, so I could go there repeatedly and study that location in all seasons, all weather, and all light. As I love walking among trees and have been visiting the Morton Arboretum since my college days, it was a natural choice. The public responded to my pictures and that encouraged me. I kept at it for twenty-two years! People, friends, and the public frequently ask me what camera I use, what lenses, and other questions about how I take pictures. Since my answer is not the technology but being present and waiting for special moments, it’s not something I can explain in a sentence or two. It takes a book. And then, the Morton Arboretum’s centenary was coming up, so I decided to put them all together:

- My favorite photographs of the Morton Arboretum

- My story of how walking among trees fills me and re-fills me with peace and regeneration.

- How I take pictures, which is not by following the rules of composition, or any rules, but by being there, being present, and feeling the moment.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

My father, an avid photographer, gave me my first camera and taught me to develop film and make prints in the darkroom. I was soon taking photos of everything that intrigued me. I talked my sister into throwing rocks in the pond so I could photograph the splash. On the north shore of Lake Superior, my uncle showed me how to set the camera for a time exposure, balance it on a rock, and wait until I had pictures of the lightning strike out over the water. I loved being able to show nature-in-action on film. But even more, I loved taking pictures of leaf and branch reflections in water, shadows on snow, and all the designs I saw in nature.

Having noticed my interest in photography, my English teacher gave me a copy of The Family of Man, a compendium of Edward Steichen’s traveling photographic exhibit of the same name. I was enthralled. I had never seen pictures like these. It dawned on me that the best pictures here were more than a physical record of a person or a place. These pictures transported me to a different place and time. These pictures carried meaning. These were the kind of pictures I wanted to take. I soon learned that taking good and meaningful photographs was not easy. But I was inspired to keep trying.

Later I discovered the black and white photographs of Paul Caponigro and the color photographs of Eliot Porter. While Ansel Adams’ brilliant mountain photographs impressed me, as a Midwesterner, I connected more to Caponigro and Porter because of their subject matter. Like both of them, what I photograph is physically closer to me, the sun on a few simple leaves, the designs I see in tree branches. Their photographs set an even higher bar for me as an artist because their photographs transcend their subject matter. Their photos reveal what it feels like to be there the moment the photograph is taken. From then on, I wanted to take photographs that show what it feels like to be in the presence of nature.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

When I started my project of photographing trees and the nature around them at the Morton Arboretum, I assumed I would create my best pictures by carefully applying the “rules of composition” to create strong landscapes. But over the past twenty-two years of taking pictures every week – sometimes every day at the Morton Arboretum – my best pictures don’t result from applying rules of composition. Instead, they happen when I’m able to dismiss logic, avoid calculating, and abandon myself to all that I am feeling and sensing in a particular place at a particular moment. Another way to say it is that “something stops me” in those particular moments and I sense “there is a picture here.” Then, I aim my camera and look at the arrangement of lines, shapes, and colors on my camera screen. Then I change my viewpoint, watching the lines, shapes, and colors reorganize as I move, watching for the moment when the view on my screen “feels just right.” It’s not that I say all this to myself when I take a picture. Nevertheless, I believe what I’m feeling (when a scene feels “right”) are these three things:

- “Balance” inside the scene of what I see in front of me.

- “A spark of freshness/newness” when the branches, leaves, or reflections have a look I’ve not seen before, and

- “Completeness” when what I’m seeing feels complete. Nothing extra is cluttering up the scene, and everything I see needs to be there.

Completeness in a photograph is akin to how a good story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. For a photo to live on, to be a picture that I and others will want to look at again and again and again, I believe I (and all of us) need to see balance, freshness, and completeness on our camera screen. When I feel those, I press the shutter.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel, or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

Myth #1: To experience the benefit of nature, you need to leave your technology at home. Instead, I encourage people to take a smartphone/camera along whenever we go for a walk in the woods. Planning to take a few pictures can extend the time we spend in nature and deepen our experience of peace and wonder as we look to distill a bit of what we’re feeling, into a photograph.

Myth #2: Following the rules of composition is the key to getting good pictures. In photography, following composition rules can lead to static, stodgy pictures. These rules may be helpful for painters and artists who start with a blank canvas. But for photographers, the camera screen is not blank. It is already full of lines, shapes, and colors that tend to look like a jumble. Instead of following rules, practice seeing what’s in front of you. Look for what feels fresh and new to you. It’s not about rules of composition. It’s about you, what you’re feeling as you engage with nature. Feel your way towards finding pictures that distill a little of what you’re feeling when you’re outdoors.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

We are all photographers now. We all have what it takes to take better pictures of the nature around us, near where we live. And go local! Ansel Adams took great photos of Yosemite – but he lived there for twenty years. When Claude Monet settled to paint, he didn’t head off to the Alps. He went to Giverny and painted lily pads and haystacks. He found beauty in nature nearby, in the nature around him. You can take your best and most meaningful pictures near you, near where you live. You will take your best pictures when you photograph the things you love. You will improve your pictures by focusing on subjects that are meaningful to you – places and people you love. Seeing nature (even a tiny plant bursting its way up through the sidewalk on your street) will offer you peace, rejuvenation, and the promise of a great picture.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I’m always reading two or three books at a time. As a groundwater scientist and a photographer, my favorite topics are science, art, and nature, with a sprinkling of biographies. When Walter Isakson, James Gleick, or Simon Winchester release a new book, I read it. My book stack for the past six months includes The Englishman by John Staddon, How Photography Became Contemporary Art by Andy Grundberg, The Accidental Universe, by Alan Lightman, Art & Fear by David Bayles & Ted Orland, and The Wild Places by Robert MacFarlane. I read Thoreau’s Walden through once, long ago, but I often pick it up, open it, and read a few pages. I do the same with In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, a Sierra Club book of Eliot Porter photographs with selected Thoreau text. I’m a music fan, blue grass especially now that I live in Nashville, but all kinds of music. (I made cellos before turning to a career in science.) I’ve been a faithful listener to The Midnight Special WFMT radio show with host Rich Warren for years and now with host Marilyn Rea Beyer.