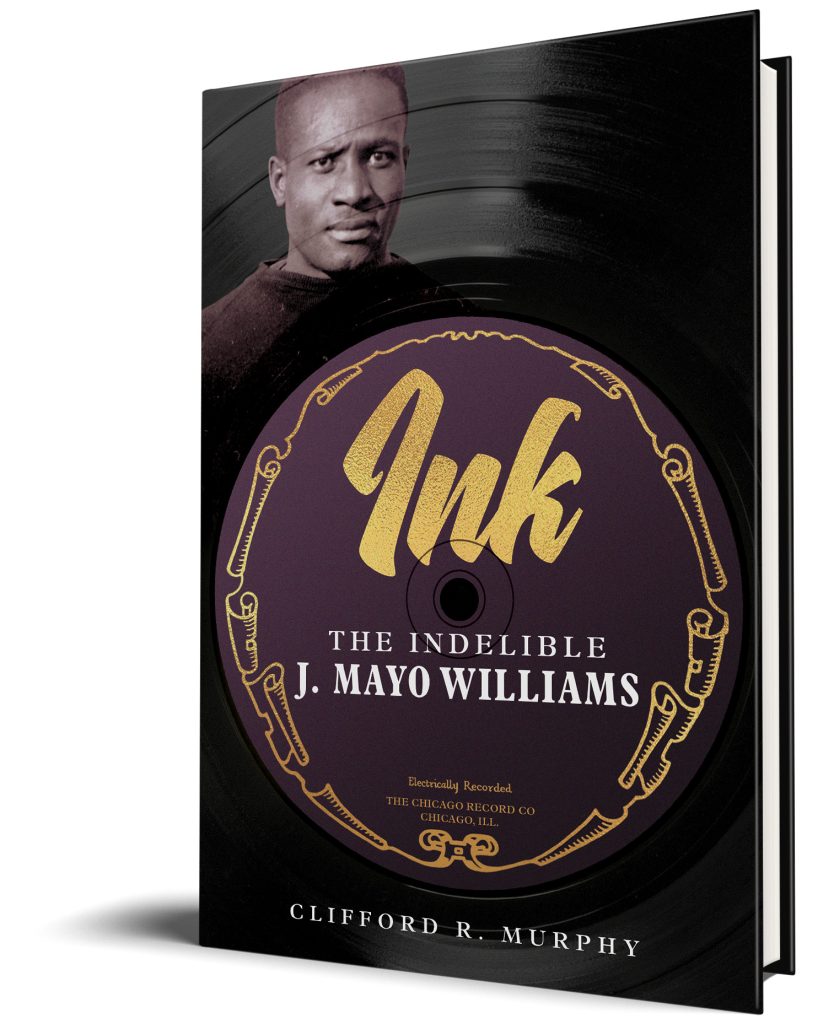

Clifford R. Murphy, the author of Ink: The Indelible J. Mayo Williams, answers questions on his new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I felt that this book had to be written. History is a scaffolding for understanding how we got here. When there are major pieces of the scaffolding missing, the whole structure is at risk. I went through a period where I wondered if, ideally, someone else should write this book – but after the release of the film Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, where Williams is rendered invisible, I felt a significant sense of urgency to complete the manuscript.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

The most stunning discovery I made was that J. Mayo Williams was the first Black man to officiate an NFL game, and that he did so in 1921, decades before Burl Toler (first Black on-field official, 1965) and Johnny Grier (first Black referee, 1988) broke barriers. Williams’ served as a head linesman in an official NFL game in Chicago between the Chicago Cardinals and the Akron Pros in 1921. I learned this fact while reading through every issue of the Chicago Whip from 1921-1922, and I almost fell out of my library carrel when I found the story – which was also reported in the Chicago Defender. The idea that the first Black official in the NFL was also the preeminent producer of blues and R&B in the early 20th Century is astounding.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope this book helps us to dispel the myth that civil rights progress in football started in the 1940s. The NFL was born as a racially integrated league in 1920, but developed a “gentleman’s agreement” barring Black players from 1933-1946. One of the dangers of dividing football history into “modern” and “pre-modern” periods is that it obscures hard and extraordinary truths that help us to better understand where we are today.

I also hope this book helps to show what a dynamic, creative, and resourceful role J. Mayo Williams played in shaping the catalog of Black vernacular music from the 1920s through the 1950s. People involved in cultural production can occasionally catch lightening in a bottle. But it takes a special person to record the string of musical luminaries that Williams did over four significant decades: Ma Rainey, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Pine Top Smith, Georgia Tom, Leroy Carr, Memphis Minnie, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Peetie Wheatstraw, and Louis Jordan to name a few.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

I don’t know about interesting, but the most exhilarating is to see the page proofs. This manuscript had a twenty year run as a Word document, or a printed Word document with notes scrawled all over it, or as a copyedited manuscript with tracked changes. And then, one day, those edits have been made, accepted, and the manuscript looks like a book. Along that journey, you never forget you’re working on a book, but you maybe forget the day will ever arrive that it will actually be a book! And so getting the page proofs is pretty exhilarating.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

Keep those research files organized from the very beginning! Take it from someone whose hard drive shattered into dust. Really! I had all of my Mayo Williams files on an external hard drive, which failed one day – so I sent it in a panic to one of those very expensive forensic labs. When they contacted me, I was worried about how much it would cost to retrieve the files. Instead, they told me the innards of the drive had shattered into dust. Fortunately, I kept backups, just not consolidated backups. Over the course of researching and writing this book, I started and finished two graduate degrees, had four children, moved three times, had three jobs, and lived through a pandemic. Think about the sheer number of laptops, desktops, flash drives, cloud storages, and external hard drives where different bits of research might get stored in a pinch. It is good to have everything backed up – twice! – both digitally and on paper. It took a lot of work – and a fair amount of panic – for me to reassemble things. Even still, I lost some stuff, and I lost track of the fact that I hadn’t secured permission to publish pieces of an important interview. I realized this as I was wrapping up another component of permissions – by which point, it was late enough in the process that I inadvertently caused offense when I asked for permission. I am lucky – and readers are lucky – that the scholar in question gave me the benefit of the doubt and graciously granted permission. But that is a bridge I hope other scholars/authors can avoid. I should have known better – but until it happens to you (or until you hear some terrifying tale like this one), you might keep whistling past the graveyard.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

Reading truly for fun? For a while, my summer reading always involved a baseball book. Favorites included Sparky Lyle’s memoir, The Bronx Zoo; Daniel Okrent’s Nine Innings; Robert Peterson’s Only the Ball Was White; Mike Shropshire’s Seasons in Hell, and Buzz Bissinger’s 3 Nights in August.

For fiction, I have truly loved reading Louise Erdrich’s novels – in particular, The Plague of Doves, The Round House, and The Night Watchman. These are books that speak to deep trauma, yet ripple with joy, and contain rich observations on nature, music, generations, and living traditions. And her books have no shortage of dry humor. That’s a potent combo for me – in life, music, and literature.

My television and film watching habits will impress nobody, and will likely disappoint everybody. But I will admit this, however: if I have had a bad or sad day, there is no better medicine for me than improv comedy: particularly Wayne Brady singing an improvised rock opera on an esoteric subject. Always brilliantly hilarious. Always good for what ails me.

For music, Willie Nelson’s stretch of records from “Yesterday’s Wine” through “Stardust,” any record made by Otis Redding – but especially his performance of “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” at the Monterey Pop Festival, Wilco’s “Being There,” S.G. Goodman’s “Teeth Marks,” Joan Shelly and Nathan Salsburg’s music, the Piedmont blues of any of the artists documented in “Blues Houseparty” (but especially Phil Wiggins and John Cephas), Charm City Junction’s “Salt Box,” and any vintage trucker music. To name but a little of the music that brings me to a happy place – even the sad songs.

Clifford R. Murphy is a musician and ethnomusicologist. He is a founding member of the rock band Say ZuZu, the director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, and the author of Yankee Twang: Country and Western Music in New England.