“All the essays in the special issue contribute to this new mapping of realist practices in the era of Reconstruction.”

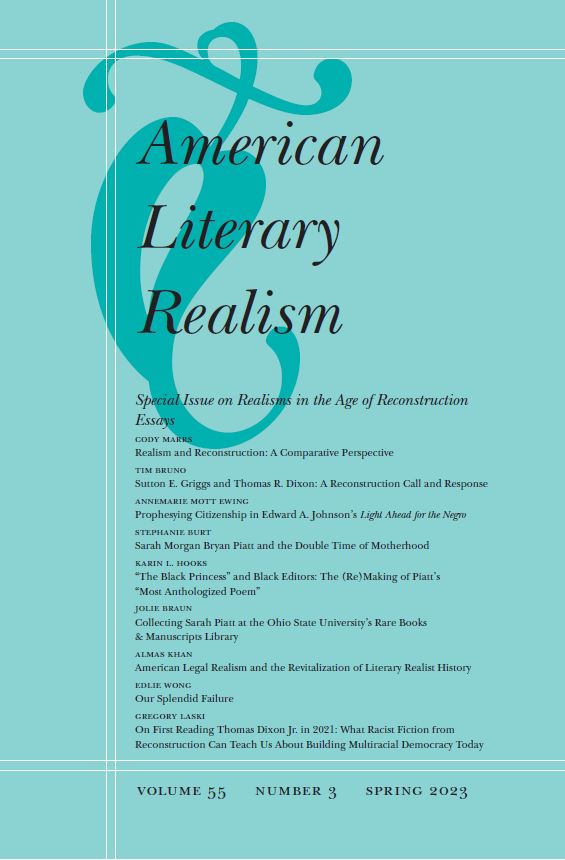

American Literary Realism is proud to announce a new special issue: Realisms in the Age of Reconstruction, available now! To learn more about the special issue, we asked guest editor Elizabeth Renker to answer a few questions about the special issue.

How did this special issue come about?

I have been working on the postbellum period for a long time. My 2018 book Realist Poetics in American Culture, 1866-1900 emerged from the larger question of why American literary history has mostly ignored or derided most of the active poets of that period, with the notable and almost sole exception of Walt Whitman. The discipline’s earliest configurations celebrated this same period for what was sometimes called “the rise of realism” (later called “American literary realism” to distinguish it from realisms in other nations) but treated realism as an innovation mostly transpiring in prose fiction, while poetry allegedly languished as an increasingly obsolete, genteel art form. My book tracked how and why this story of the “twilight of the poets” came into being in tandem with the rise of realism. I also recovered a diverse array of realist poets across print culture, including women and poets of color. The exhaustive research for that book tackled disciplinary myths and problems related to realism, and it also pulled my scholarly focus more and more into Reconstruction. Realism and Reconstruction were of course happening at the same time. So, one of the results of writing the book was that I got more and more interested in how and why the discipline (as well as American public culture more generally) evaded Reconstruction.

Can you give us a short take on the special issue’s title?

The title uses the plural term “realisms” to reflect the fact that disciplinary ideas about American literary realism have changed significantly since around 1980, roughly the time of the canon wars. Around that point, disciplinary focus shifted from a pantheon of “great authors” (William Dean Howells, Mark Twain, Henry James) to a much more inclusive array of writers, including women and writers of color. (But still, to return to my earlier point–no poets). Ideas about the origins of realism in the U.S. also pushed backward, from the 1880s to the 1860s, and so on. In these ways, definitions of American literary realism have already changed significantly over time. Using the plural term “realisms” signals that the special issue is moving beyond an earlier phase of disciplinary history and into a new set of questions, this time concerning Reconstruction as the historical frame. It is common for people to misunderstand realism, assuming it is a form of writing that adheres to a monolithic quasi-journalistic style or that sticks to certain types of gritty subject matter and so on. But those are misunderstandings. A diverse array of writers engaged in realist projects that looked very different from one another. All the essays in the special issue contribute to this new mapping of realist practices in the era of Reconstruction.

How would you explain the relationship between Reconstruction and realism to someone outside the field?

Put most starkly, both are happening at exactly the same time. They are thus bound up together. New scholarship by historians including Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur defines Reconstruction as the era stretching from the Civil War until the rise of Jim Crow at the end of the nineteenth century. So, the complex and violent history of Reconstruction, including early progress in civil rights for Black people that was then aggressively shut down, played out across the decades of the “Age of Realism.” The roiled sociopolitics and competing ideologies bound up with Reconstruction were part of the social fabric, including the daily print culture, during this time. It’s simply not possible to separate the thick history of Reconstruction from what realist writers were thinking, doing, reading, writing, and living.

This issue has a few articles (See Burt, Hooks, Braun) that focus on Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt. Can you tell us a little about her work and why it’s an important part of this issue?

As I mentioned earlier, poetry has mostly been left out of American literary realism. My book argues that Piatt was a major realist poet. She was a popular and acclaimed woman poet during the “Age of Realism”; she was championed by Howells; and her life and her extensive body of work were embroiled in the sociopolitics of Reconstruction. A white Kentuckian born into two slaveholding families, she married into a family of avid Ohio Republicans; she lived in Washington, D.C. during the Civil War while her husband worked for the Lincoln administration; she lived in Ireland for over a decade when ideas about U.S. Reconstruction were a transatlantic topic applied to Ireland as a British colony. Definitions of poetry in her time often expected poets to write in an idealist mode. Piatt was well aware of these expectations, and she defied them. Over a career spanning the latter half of the nineteenth century, she carved out a realist poetic practice that gave her access to print under what often served as genteel cover. But like so many other woman writers, she fell from view in the twentieth century. Piatt now stands at the brink of the canon, one indication of which is that she has just been included in the new 10th edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature. It’s my hope that future issues of ALR and other journals will run clusters like this one on other lost or neglected poets of the Reconstruction period. I’ve love to see future clusters, for example, on the largely neglected Black poets Priscilla Jane Thompson, George Marion McClellan, W.H.A. Moore, and Henrietta Cordelia Ray.

Can you say just a bit more about why it was an opportune time to publish a special issue on the conjunction between realism and Reconstruction?

Michael Davitt Bell’s iconic 1993 book, The Problem of American Realism: Studies in the Cultural History of a Literary Idea, foregrounded what he called the “problem of definition” that had long dogged discussions of American realism. Thirty years after Bell, this special issue sets out to address what I’d call a problem of redefinition: writing a new history of American literary realism that places it squarely in the era of Reconstruction. The contributors to the special issue, from a variety of areas of expertise, address a selected array of questions and problems that help to open that door. All of them contribute to this new literary history. There is so much more to be done.

View the full Table of Contents for an overview of the material included in this special issue.

Elizabeth Renker, PhD, is a professor of English at The Ohio State University. Her areas of scholarship include nineteenth-century American literature, particularly the U.S. Reconstruction period and the Gilded Age; American literary realism; poetics, especially the social life of poetry; the history of English as a discipline, including “American literature” as a field; and the recently rediscovered poet Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt (1836-1919), whose biography she is now writing.