In deciding to write a book on the history of my hometown (Salisbury, NC), I became keenly interested in family history. As a historian, I am perhaps naturally fascinated with the past; however, genealogy had not been a principal preoccupation of mine prior to researching the lynchings that took place in Salisbury in 1902 and 1906. My mother, Elizabeth Burton (formerly Elizabeth Clegg), was my first point of entry in regard to learning about the more recent past of Salisbury. Further, she was also a vital link for connecting me to this history in ways that I had previously been unaware of.

What follows is an excerpt from an early draft of the epilogue of my book, Troubled Ground, which I later determined was too personal and autobiographical to include in the final draft of the project. I am still not sure if this was the right decision. In any event, I think the following story captures the ebb and flow of race relations in Salisbury seventy years after the lynchings, as well as my own investment in the telling of this tale.

*****

When Elizabeth Clegg found herself sitting nervously on the front step of her new mobile home in an all-white trailer park in 1972, she had already learned enough about race relations in Salisbury to amply justify her anxiety. She had been born in the area to parents who struggled to provide for a family that would eventually include eleven children. During her childhood, she and her siblings had picked cotton for white landowners to help make ends meet while attending the local public schools for African Americans. As she would tell me years later, she had early in life become accustomed to a racially segregated world structured in a fashion to ensure white supremacy and black deference. Like other southerners born during the baby-boom generation following World War II, she rode on city buses in which African Americans were expected to sit in the back seats. Moreover, her high school was dependent upon used textbooks that had been passed along by local white schools that had received newer editions. For decades there had been no habit of voting among the blacks of Rowan County, in which Salisbury was the seat of local government, due to state laws and area customs that sharply suppressed black electoral strength. Even after she married Claude Clegg, Jr., a native of Lillington, in 1967, they still could not eat at a table in local white-owned restaurants, instead having to receive their orders at a backdoor designated for black patrons.

In Salisbury and elsewhere in the South, racial segregation was so thoroughly embedded in the lives and experiences of blacks and whites that it could often take on a normalcy that rendered it virtually invisible, or at least unremarkable. Its man-made roots and white supremacist architecture could become startlingly noticeable when one experienced one of its many insults and inconveniences, such as having to walk a mile or so to find a “colored” restroom when a better-furnished “white” one was only a few steps away. Despite these crude, even nonsensical, elements of the system, whole generations of southerners grew up under the watchful eye of Jim Crow, with the racial boundaries of their lives policed with varying degrees of vigilance by parents, neighbors, teachers, ministers, lawmen, and others.

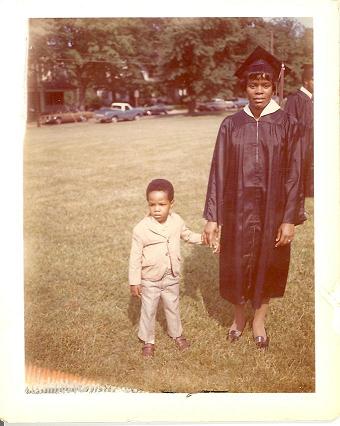

My mother, Elizabeth, entered adulthood during a time when the country was on the cusp of notable social change. Hers was the last generation of Rowan County young people to be legally segregated by race in public schools, and she would have future opportunities that were almost wholly unknown to African American women of the past. After high school, she matriculated at Livingstone College, a local black institution operated by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. She majored in business education, earning a baccalaureate degree in 1971. She was immediately offered a teaching job in China Grove, a town in the southwestern corner of the county where she had recently served as a student teacher. Her mother and others had cautioned her against taking the position at South Rowan High School, since China Grove had a known history of Ku Klux Klan activity. She decided to accept the job anyway, despite ongoing racial turmoil on campus in the wake of court-ordered desegregation. Elizabeth, one of only a few African American teachers ever employed by South Rowan, would work there well into the 1980s. She would eventually have many stories to tell about her time there, whether about the bitter controversy over the school’s Confederate-inspired symbols—including a “Rebel” mascot and “Dixie” anthem—or the occasional white student who sought her out after graduation to express gratitude for her mentoring. I suspect that she spared her two young sons—my brother, Jeff, and I—the details of her most trying days, though we could sometimes tell how the job wore upon her.

While early experiences in Salisbury and China Grove may have prepared her to venture forth alone as a single mother, things were not meant to happen that way. Elizabeth married young and promptly had two sons a year apart. My grandmother had warned her to wait before making such a commitment, at least until she finished college. However, the couple was in love and settled for nuptials before a South Carolina justice of the peace. The marriage was turbulent from nearly the start, and I vividly recall strife in our East Spencer apartment as one of my first memories. By the early 1970s, my parents were enduring one of several temporary separations that would eventually lead to divorce by 1980. After deciding to leave the apartment on Long Street, Elizabeth used her teacher’s salary to make a down payment on a single-wide mobile home. The next step was to find a lot to rent in a trailer park open to blacks, a task that turned out to be more difficult than she had predicted. Following a number of failed attempts to find a space for her trailer, Elizabeth learned that a Mr. Everhart, one of the petty real estate magnates of the area, owned two mobile-home neighborhoods on the outskirts of Salisbury. Tucked away in a corner of the city where the streets turn into routes, the property was still segregated into two different communities, with the black trailer park situated above the white one on a densely wooded hill. My mother, a product of the race relations and social realities of the time, requested a lot in the black area. Everhart informed her that none were available, but offered a spot in the white neighborhood. Reluctantly, she accepted the offer, and the trailer was delivered to the new place of residence.

Elizabeth did not sleep at all during her first three nights in the neighborhood that she had just integrated, albeit in a token fashion. It was fear, plain and simple, that deprived her of slumber, exacerbated by the added burden of making sure that this needling apprehension did not touch loved ones—in this case, her two boys, ages three and four. I personally do not remember the move into the new trailer or insomnolent nights accented with caution peeks through the curtains. Apparently, my mother had convinced Jeff and me that we were safe and secure during those initial nights, and we slept assuming as much. The first night turned out to be uneventful, but that was simply day one. The following two nights were spent in the same fashion as the first, with Elizabeth sitting petrified in a dark room hoping that a fire bomb or some other disruptive force would not consume her and her boys who slept carefree in the next room.

The following morning, Elizabeth sat on the front step of her trailer, cautiously attempting to show herself friendly while not risking a more active test of neighborliness. She graded papers to pass the time, just as she had done on the previous three days. Her sitting was more waiting than anything else, a nerve-wracking exercise aimed at discerning what might come after night fell again. But this time, the waiting finally came to a head. A white woman sauntered across the yard, crossing the imaginary boundary where the yard of one trailer ended and another’s began. I do not recall us ever having much in the way of grass in the front yard; the graveled driveway is easier to recall. Thus, the woman’s approach may have been accompanied by dusty footsteps or an otherwise more rugged-looking movement that would have been softened had we had a lusher yard. Fortunately, the shoddy landscaping did not matter. The woman had come with an open hand and kind words of introduction, welcoming Elizabeth to the neighborhood. That night, my mother finally slept.

*****

Claude A. Clegg III is a professor of history at Indiana University and the author of Troubled Ground: A Tale of Murder, Lynching, and Reckoning in the New South.