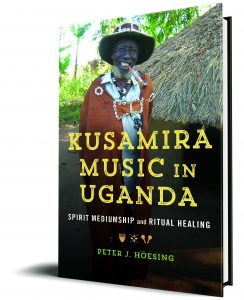

Peter J. Hoesing, author of Kusamira Music in Uganda: Spirit Mediumship and Ritual Healing, answers questions on his scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways in his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

There’s a rich African Studies literature across anthropology, history, religious studies, and philosophy on ways of knowing and being in this region, but so few of them address music as a lens for these repertories of knowledge and action. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology has done some fantastic publishing with other ethnomusicologists working with trance and mediumship traditions elsewhere around the continent. I wanted to illuminate the musical and ritual particulars of a very old constellation of practices in Uganda. I also want to encourage other ethnographers to keep working in the broader region: these repertories have correlating traditions all across Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania and beyond.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Above all, my Ugandan teachers and field consultants have been my most formative influences in the ideas that emerge here. Damascus Kafumbe and Sylvia Nannyonga-Tamusuza have been carefully, consistently, and constructively critical through that process of building trust with other folks in-country. My doctoral thesis advisor, Frank Gunderson, and an anthropologist on that same committee, Joseph Hellweg, inspired my devotion to indigenous African languages as an essential methodological tool for this work, and their examples helped me understand the difference between dissertation and book. They did so much more, too, but having scholarly mentors who are fluent in languages like Kiswahili and Kisukuma (Gunderson) and Bamanankan (Hellweg) in addition to the colonial languages they had to know to examine documents of that era? That’s a mountainous example to live up to, and I’m still working at it. Frank introduced me to Steven Feierman’s work, and I later met a whole bunch of Feierman’s students, all of whom shaped my thinking. The book shows the obvious influence of historian Neil Kodesh and his doctoral thesis advisor, David Schoenbrun, as well as ethnomusicologists Rich Jankowsy and to some extent Steve Friedson.

At the Press, Laurie Matheson facilitated the earliest discussions about the transformation of this work from dissertation to book with a folklorist named Sharon Sherman, several other fascinating first-time book authors at various career stages, and two other university presses. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that it was Laurie who inspired me to really hone the ideas in this book about repertories. A word to authors in humanities, music, and social sciences looking for book publishers: you will find in Laurie a razor-sharp intellect and an open mind with a generous spirit to match. She’s also a musician, which I found equal parts fun and rewarding along the way.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

That’s a tough question to answer because there are so many possible answers to it. I think good ethnography helps us understand something about human behavior. I could say something about the linkage between music and well-being, but people will get that in the book. Because of the broader social and political context from which this book emerged, and because of when I was working on the manuscript, I think the lessons here about cultural humility are the most interesting discoveries. That extends to aesthetics, therapeutic methodology, all kinds of domains. Every culture has some historically durable social institutions. If we really want to know what those are, what they are worth to people, and why they matter, we absolutely must listen and observe. Ethnography is research on human behavior, and musical ethnography requires writing about musical behaviors, so they demand close listening. They demand cultural humility. That’s not a new discovery, but current events remind us that listening and learning from people is as important now as it ever was.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

There’s a tired stereotype about all African healing as witchcraft that is so obviously an oversimplification motivated by power and control. Can we just agree to let that one die? I hope this book has something in common with so many books across a staggering variety of African traditionalist paradigms: it parses terms and practices carefully. It distinguishes spirit possession from spirit mediumship, and it demonstrates through language and ethnographic description that sorcery and witchcraft are also discrete categories of practice and experience. Musical repertories turn out to be a utilitarian way to do that because they illustrate how music socializes and perhaps normalizes something that people might otherwise regard as a rather esoteric spiritual experience.

Given the existence of trance practices all over the world, and their cultural specifics within all of the world’s most widespread religious traditions, I hope one of the colonialist myths this book will push back against is the notion that these somehow offer evidence of devil worship or demon possession or anything like that. The people I consulted consistently rejected this as a product of missionization by both Christians and Muslims. They insisted that religious belief and cultural beliefs can coexist. That inspired one of the main themes of the book: I argue that the musical textures at play in kusmira reflect an aesthetic of simultaneous iteration. That aesthetic of simultaneity has as much social and religious resonance as it has cultural and musical logic.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

I really want readers to see how music is such an important part of what makes us whole, well humans. I want them to see how that makes African music really distinctive, and I also want them to see how it is common across many cultures. If they really take that seriously here, if they begin to see some similarities and differences in how the people in this book use music and how they use it, if they can hold all that in balance, maybe they can look around and see how it works elsewhere, too.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I grew up playing jazz, and mid-20th century bebop, post-bop, and hard bop are probably still my most frequent go-to recordings, but I listen to everything: Afropop and American hard rock/metal are great for workouts; Hindustani and Carnatic [Indian] classical for yoga or just head space; Gaelic, Eastern European, and American folk musics are all fascinating (the older I get, the more I especially like real, classic Country); and of course I never truly get enough African traditional music. The diversity of instrumentation and style and the linkages across the continent keep me rapt with attention. When it’s news instead of music, NPR is my companion in the car.

I love reading fiction: Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi is a Ugandan literary phenom whose work I can’t get enough of right now.

I love visual art, too, and my spouse was raised by an interior designer with a great eye for visual analysis, so I learn every day from them. I’m checking out a lot of Michaela Pilar Brown’s work right now. Fahamu Pecou is a long-time favorite, and I get hipped to a lot of the East African arts scene via the StART Journal in Kampala.

Our watching habits are as eclectic as any of this. We’re probably typical of an academic’s household in that regard. Yellowstone is a smart critique of neocolonialism and land use in the American West. Good Girls offers dark, hilarious reflections on the ridiculous number of resources it takes to maintain a family household and what people are willing to do to accomplish it. Along with a truly inspiring cohort of his contemporaries in drama, TV and film, Jordan Peele’s horror is giving people a real, honest look into what scares Black Americans and why. We call PBS “nerd-o-vision,” and predictably, it’s our favorite source for so many things from information to entertainment.