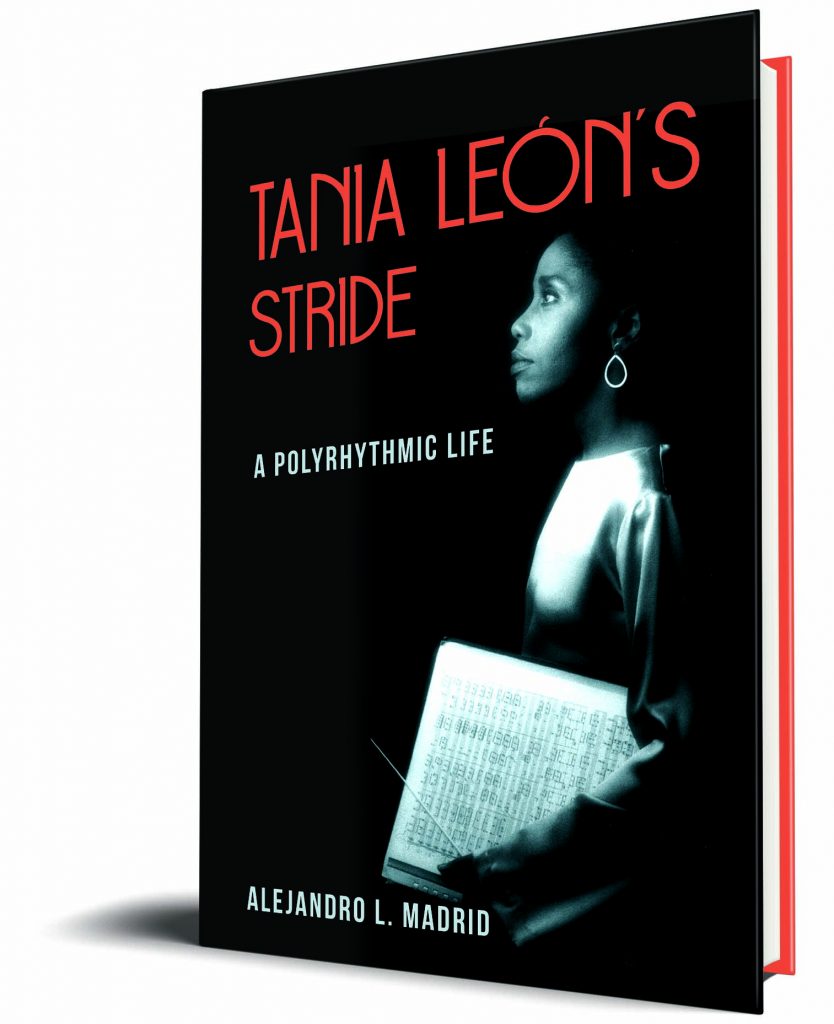

Alejandro L. Madrid, author of Tania León’s Stride: A Polyrhythmic Life, answers questions on his scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

This question requires a long answer. I had known about Tania León since the 1990s, when I was a graduate student in New York; but I did not have a chance to meet her until the late 2000s, at a conference on Latin American Music at Indiana University. Later, in 2014, I got to know her better when she came to Cornell to speak about her music to our composition students. Sometime after that meeting, a few colleagues and mutual friends approached me with the idea of writing a book-length biography of her (the book was commissioned by Brandon Fradd and The Newburgh Institute for the Arts and Ideas). She was also happy about the possibility of me writing it. However, I was hesitant about taking on the project. My previous book was a study of Mexican microtonal maverick Julián Carrillo, which had taken me many years to conceptualize as an “anti-biography” in an attempt to avoid the naïve celebratory tone that you find in many biographies; which often end up being more hagiographies than critical intellectual interventions. The fact that Carrillo was not alive when I wrote that book allowed me to take distance from him and write a book that was very critical but also provided an assessment of works and ideas that had remained obscure until then. But that was not the case with Tania León, who is not only alive but had a very specific agenda regarding her biography. Nevertheless, I kept thinking about the unfair fact that regardless of her being one of the most salient composers of her generation and an inspirational role model in the U.S. classical music scene, nobody had written a serious study about her or her music. I felt there were several issues playing against her for that to happen, she was a woman, she was Latina, and she was black in a professional field in the United States that systematically disregards or marginalizes the achievements of women, Latinxs, and blacks or, at best, celebrates them in a tokenistic fashion. Also, being a native of Cuba who had immigrated to the United States pretty much insured that nobody on the island was going to write about her. So, I thought that not only Tania León deserved a major biographical study but also that music audiences and music scholars also deserved to know more about her and her inspirational life and work. The problem for me was to figure out a way to tell her story without falling in the traps of the conventional biographic genre that I was so critical of in my anti-biography of Julián Carrillo. I needed to keep a critical distance from someone I admired —and who I came to admire even more as I got to know her better through the process of researching and writing this book. In the end, I think I managed to do just that by developing a narrative in which Tania León’s voice is always heard in counterpoint with those of her relatives, friends, mentors, mentees, and colleagues to create a rich but easy-to-read text that illuminates her life and work in relation to the immigrant experience in the United States, the Cold War, the struggle for civil rights, the construction of personal and collective identity, and the navigation of diverse transnational cultural networks. So, in sum, I got interested in writing this book because I felt that telling Tania León’s story was a way of opening the door for others to tell the many stories that continue to be rendered invisible in mainstream U.S. culture due to race, ethnic, and gender issues.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

For this particular project I was inspired by the innovative and beautiful work on music biography by Jocelyne Guilbault, Ellen Harris, and Shana Redmond. They have all been very interested in finding new and more interesting ways of telling stories about musicians’ lives that avoid the genre’s commonplaces, that assert their method’s dialogic character, and that articulate the political potential of rethinking the genre’s coordinates.

Beyond academia, I think my take on biographical and anti-biographical writing owes much to Mirror, a wonderful film by Andrei Tarkovsky that suggests that it is impossible to understand the past without thinking about it in relation to the present and the futures that may or may not have happened. I think you can see that logic informing many passages in Tania León’s Stride.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

Finding out of the details of Tania León’s professional relationship with Arthur Mitchell and the Dance Theatre of Harlem was fascinating. There is very little research done on this historical ballet company and although one hears stories through the grapevine it was fantastic to actually hear them and learn about them from the dancers, choreographers, and musicians who lived through the experience of founding this company. In that sense, Tania León’s Stride will be illuminating not only for those interested in Tania León, her works, and her life in the New York contemporary music scene since the 1970s; it will also provide important information to people interested in learning more about the history motivation, and working methods at one of the most important African American ballet companies in the history of United States.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope readers realize how incredibly difficult it is for someone to have to leave their country of origin in order to start a new life from scratch somewhere else. In a time when media and mainstream speech disparages immigrants —especially immigrants of color—, nothing better than to get to intimately know about the struggles that these individuals go through in their everyday lives in order to empathize with them. Also, in a country so polarized by issues of race, ethnicity, and access to resources and opportunities, it is good to learn that regardless of affirmative-action myths thoroughly ingrained in the U.S. imaginary, people of color and women do not have it easier. Tania León’s life and experience shows that even for someone as prominent in U.S. culture as she is, discrimination, belittling, and lack of respect are obstacles that women and people of color still have to face on an everyday basis in the United States.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope that, through Tania León’s example, readers get a better idea of how music can be used to advance progressive artistic projects and causes about inclusion, representation and collective well-being without invoking identity politics or tokenism.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I have a seven year old daughter whom we are raising trilingual and thus most of my non-academic reading is done in Spanish with her and for her. Lately, we have read a series of science-fiction books for children about a character named Professor Ziper, an eco-friendly inventor who is also a big-time rock fan and who uses science to solve all sorts of problems for his friends. The series was written by the brilliant Mexican writer Juan Villoro; so, it is actually great-quality children literature. The last book I read just for fun for myself was Valeria Luiselli’s wonderful and painful Lost Children Archive.

Regarding music, I have a very eclectic taste. I hear everything from The Beatles to Silvestre Revueltas. Lately, I have been listening a lot to Mexican songwriter Natalia Lafourcade… and a lot of violin music too; also because of my daughter, who is learning to play the violin; so, we listen to a lot of violin repertory together.

When it comes to movies… well, that was actually my first passion. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a filmmaker. So, this would need to be a whole other conversation. I’ll just mention a few of my favorite directors; I tend to watch their movies over and over again: Luis Buñuel, Daniel Burman, Juan José Campanella, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Stanley Kubrick, Pablo Larraín, Spike Lee, Milcho Manchevski, Julio Medem, Andrei Tarkovsky, Wong-Kar Wai. The list could go on and on.