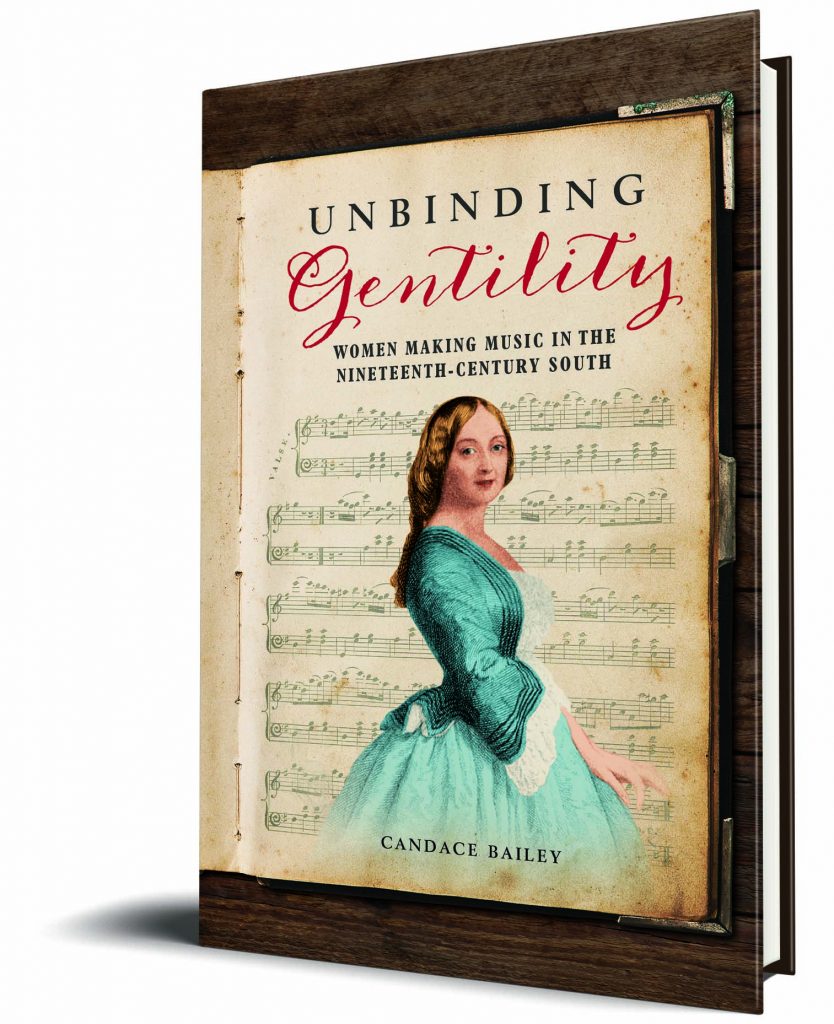

Candace Bailey, author of Unbinding Gentility: Women Making Music in the Nineteenth-Century South, recently answered some questions about the inspirations behind and discoveries she made while writing her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

In the course of my research, I discovered so much new material that conflicted with or flatly contradicted published material on parlor/women’s music. Moreover, my book Music and the Southern Belle: From Accomplished Lady to Confederate Composer dealt primarily with elite white women, but there were many more whose stories needed to be part of the narrative of music history in the United States. I wanted to determine if there was a common cultural thread that explained how enslaved Black women, poor white women, wealthy free Black women, and rich planters’ daughters all came to perform essentially the same repertory. I sought a way to understand the meaning of musicking—why women learned to read music and how they used it—across disparate voices that are rarely discussed in the same place.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Ruth Solie’s Music in Other Words: Victorian Conversations and Amrita Chakrabarti Myers’s Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston were probably the two most influential books for this project, although I could name many others. As to the study of American music in general, I owe a great deal to Katherine “Kitty” Preston, whose stalwart support of not only my work but that of other Americanist musicologists has proven invaluable in keeping the subject in the forefront of our peers. The interdisciplinary nature of this book offered the opportunity to look into a wealth of material that assisted in the formation of ideas, such as Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, Karen Halttunen’s Confidence Men and Painted Women, Lori Merish’s Sentimental Materialism, Dianne Lawrence’s Genteel Women, Sarah Case’s Leaders of Their Race, Derek Scott’s The Singing Bourgeois, and Martha Banta’s Imaging American Women. Reading period newspapers, journals, diaries, and other material also significantly influenced my views.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

This is a difficult question! Certainly, the fact that there were women in the South who carved out careers for themselves as working musicians much earlier than has been reported ranks as one of the chief discoveries. Also, bringing to light the repertory and social use of music among Black women in the South and showing how it followed etiquette patterns typically interpreted as white-only behaviors is a major contribution as well.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

Scientific musicking (making music from notated scores) did not belong to any single social group. Women from all walks of life, from a variety of ethnicities, participated in musical practice during the entire period covered in the book (roughly 1830-1880). One of the initial points I make is that we, as authors, have tended to envision the “cultivated tradition” as white, and musicking among Blacks as oral, limiting the latter to Spirituals, work songs, etc. The evidence completely dispels that premise, and I document the use of opera excerpts, waltzes, and other genres typically reserved for white Americans in Black communities across the antebellum and Civil War South.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

“Parlor music” as a concept does not do justice to the myriad ways southern women used music as cultural expression, and yet there must be something that encompassed and expressed the differences and similarities across such a wide geographical region. Gentility serves as a much more accurate way to interpret the individual variations in women’s musical culture. Microhistories of specific women and of particular places helps chart the cultural geography of the meaning of musical practice from the antebellum period through the Reconstruction. These provide a nuanced view of how culture transformed through the Civil War and how such change impacted women’s lives during the Reconstruction. Taken together, the book shifts the emphasis from “parlor music” to women’s musical practices.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I am a huge fan of Agathe Christie and enjoy both reading her books and watching various adaptations for television. Historical documentaries, other British mysteries, gardening shows, and science-based programs also figure heavily in my viewing patterns. The music I prefer to listen to for fun is essentially a conglomeration of world music, especially from the Middle East, Indonesia, and Africa, or that of J.S. Bach.