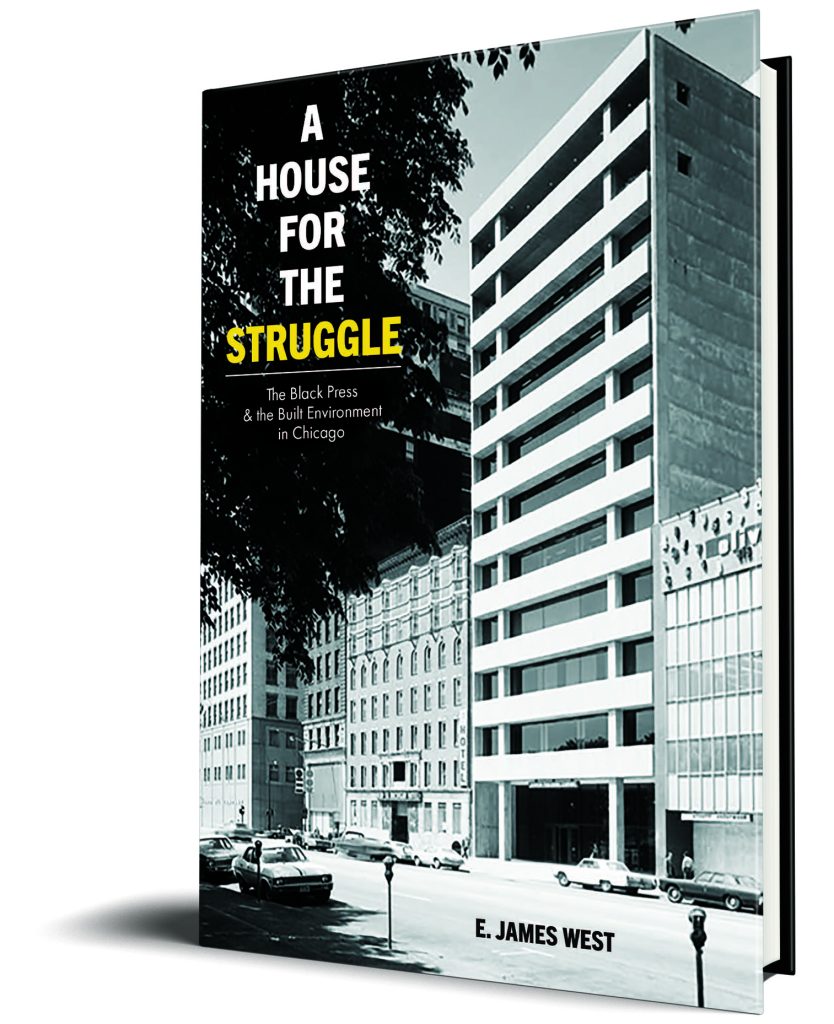

E. James West, author of A House For The Struggle: The Black Press and the Built Environment in Chicago, answers questions on his influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

My first book with Illinois, Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr.: Popular Black History in Postwar America, focuses on Ebony’s role as an outlet for popular Black history. As I was writing this book, I became fascinated by the Michigan Avenue offices of parent company Johnson Publishing. When I started to read more about this iconic headquarters, I found a window into a rich and deeply layered history of Black media buildings – not only the previous homes of Johnson Publishing, but also the offices of other leading Black Chicagoan media enterprises such as the Chicago Defender and the Chicago Bee. I realized that placed in conversation with one another, these buildings could provide a new way of thinking about the history of the Black press and of the complex connections between race, space, and media – within and beyond Chicago.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Aurora Wallace’s book Media Capital was probably the biggest influence on this project, particularly her ideas about how media outlets have used architecture and the built environment to inscribe and assert their power. In terms of scholarship on Black Chicago, Davarian Baldwin’s work in Chicago’s New Negroes is still so informative fifteen years after its initial release. Other scholars, journalists and activists influenced this project in different and important ways, even if their influence is not always visible on the page – Betsy Schlabach, Adrienne Brown, Adam Green, Ethan Michaeli, Chris Reed, and Tim Black among them.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

There are so many! I adored this project for its constant capacity to reveal new anecdotes, sidebars, discoveries and detours. I was excited to discover that the Chicago Urban League was actually based out of the Chicago Defender offices for a number of years during the late 1950s and early 1960s. This arrangement became a really useful tool for thinking through many of my ideas about the Defender’s relationship to community organizing and civil rights activism.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I’m not sure about dispelling or unlearning, but I hope my book will provide readers with a new way of thinking about the Black press and the relationship between race, space, and media production. There has been so much fantastic work published on the Black press over the past decade by scholars such as Kim Gallon, Eric Gardner, D’Weston Haywood, and others. I believe that this book complements this scholarship, but also offers something completely different; something which looks at the Black press in a fresh and really exciting way.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

That Black media buildings matter. That the actions of individual Black publishers and journalists, as well as the collective ambitions, influence, and orientation of Black periodicals, were shaped by, and helped to shape, the world around them. That the spaces and places inhabited by these people and entities – from backstreet storefronts to custom-built corporate edifices – were a hugely important (albeit often imperfect) extension of their role as a ‘voice for the race.’

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

Musically it’s a mess. At the moment I’m cycling between Sa-Roc, Cold Specks, and Death from Above 1979. So yeah, lots of emotions. Book-wise I’ve been making my way through Tayari Jones’ back catalog, which has been a very solid life choice.