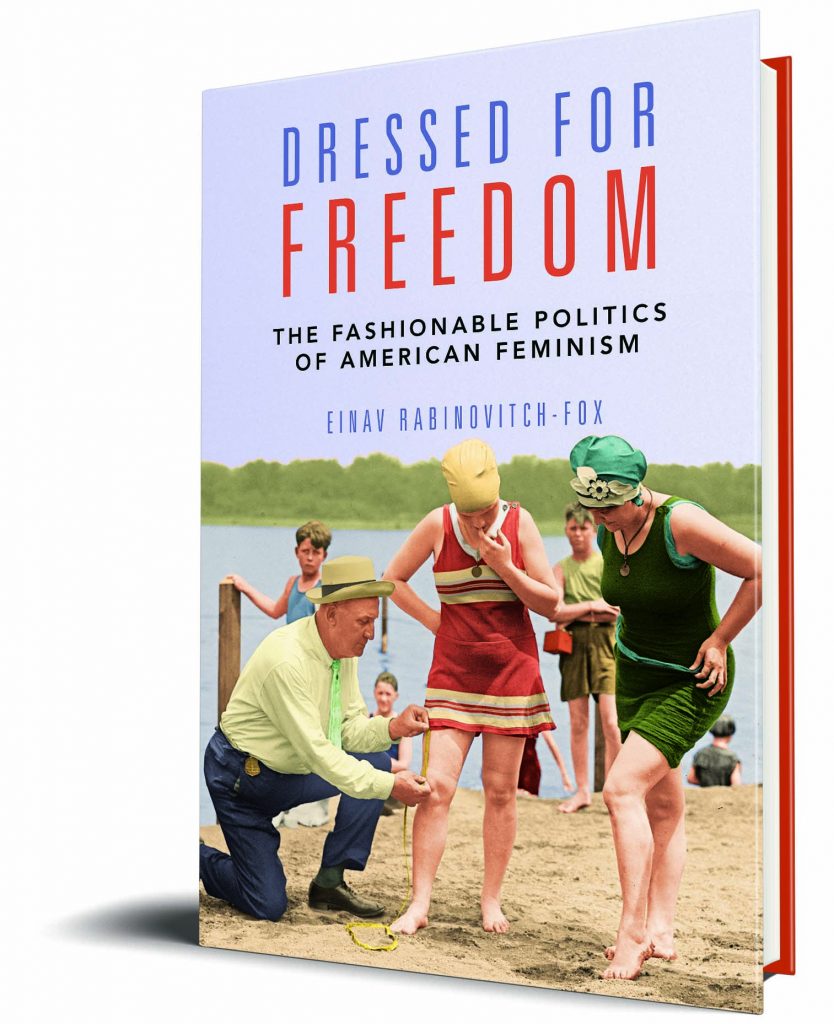

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, author of Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism, answers questions on her scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from her book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I always viewed myself as a proud feminist, but as I was growing up I kept hearing statements along the lines of: “I’m not a feminist, but…” “I believe in women’s equality, but I also like to wear high heels, so I don’t see myself as a feminist,” “A true feminist doesn’t care what she wears or about makeup.” After hearing so many iterations of such excuses, I was curious to understand why feminists have such a bad reputation of being ugly and anti-fashion. Looking to see what the origins of this stereotype were, I wanted to explore what feminists thought and wrote about fashion, and how fashion functioned in their ideology and activism. I discovered not only that many feminists were seen as beautiful and fashionable, but that they themselves often saw their appearance as a form of empowerment. It made me think there was a more complicated story to tell about the relationship between fashion and feminism, and I wanted to dig further on how seemingly marginal aspects such as clothing can serve as a useful means to express and advance political agendas.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

I’m indebted to so many scholars and historians who take seriously the role of fashion and clothing in social movements and who shaped my thinking about this topic. I was really influenced by the research of Kathy Peiss, Nan Enstad, and Tanisha Ford, who really engage with fashion both as a primary source and heuristic device. Their writing inspired me to think deeper on the social and political meanings of fashion and especially as part of history. I was also inspired from cultural historians like Phillip Deloria, Tiffany Gill, and Jennifer Scanlon who helped me think more critically about the methods of cultural history and how to write using cultural products. Fashion theorists like Joanne Entwistleand Angela McRobbie who look at the connection between fashion, gender, and feminism in interesting ways were also a source of influence. Additionally, working in museums and with fashion curators really taught me how to “think” through clothes and the value of material objects to the understanding of history. I really gained a lot of experience and skills while looking at actual costumes and thinking about them as texts.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I was pleasantly surprised to discover how central the question of clothing and appearance was to early feminists. At first, I was afraid I won’t find enough sources for my research, but that quickly turned out not to be a problem. Not only that fashion was central to feminists’ thinking and writing, but I also discovered that they were very creative in using fashion in their activism, which left a long visual and archival trail I could follow. What struck me the most however, was to discover that women organized to protest the fashion industry so they could keep the styles they found most suitable to them. In the 1920s, flappers fought to keep their skirts at knee-length after the industry sought to lengthen them. They articulated their demands in political terms, equating their “right” to wear short skirts with their newly right to vote. The same arguments were also made in the late 1940s, when women protest Dior’s New Look. And in 1970, women organized demonstrations and “clip-ins” after the industry tried to dissuade them from wearing minis in favor of midi skirts. I think that this shows us how what we wear is always political and that fighting for the length of one’s skirt is not a silly endeavor but as worthy as other causes. I wonder if today women will be ready to organize to protest corporate interest and the fashion industry, and how fashion could function in political movements.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

The greatest myth my book seeks to dispel is that feminism and fashion are opposing forces. Fashion is a powerful way of expression, and as such it was always part of the struggle to advance women’s rights and freedom. Feminists did not think that fashion is frivolous or marginal to their efforts, and they certainly did not think that it was just a tool of oppression. I think that feminists saw fashion for what it is – a tool to advance their cause but also a space where they could find pleasure and joy in what they were doing. I hope that after reading my book readers will move away from stereotypes that cast feminists as anti-fashion or that fashion is only a tool to oppress women. I want them to think about how and why clothing matter, and that fashion can be a feminist practice. There is no contradiction between looking good and being a feminist.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

I want them to think about fashion seriously. What we wear matter, and fashion can be a very powerful tool. But more importantly, I want readers to reconsider the place of joy and pleasure in politics and their everyday life. We often tend to think about the more difficult aspects of history, but I want my book to show readers that fun and beauty are also important facets of social movements and change. I would also like readers to think more about how objects and images can tell us stories, and what stories do they tell. History is often a discipline that is very reliant on words, but this book is an example on the type of questions you can answer when looking at clothing and adornment practices—and how they highlight different aspects of the past.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

As reading and writing is part of my job, I hardly read just for fun anymore, especially that in my line of research even reading women’s magazines like Vogue can count as “work.” However, I do enjoy watching films and TV shows – I will always say yes to a good drama or a thriller. I enjoy shows and movies that look at different aspects of the fashion industry, or that have interesting costumes in them, from any period, but I must admit that sometimes this experience can be a frustrating one for a historian of fashion. Nevertheless, I always enjoy good story and acting, so I welcome shows that help me to pass my time while offering a visual treat.