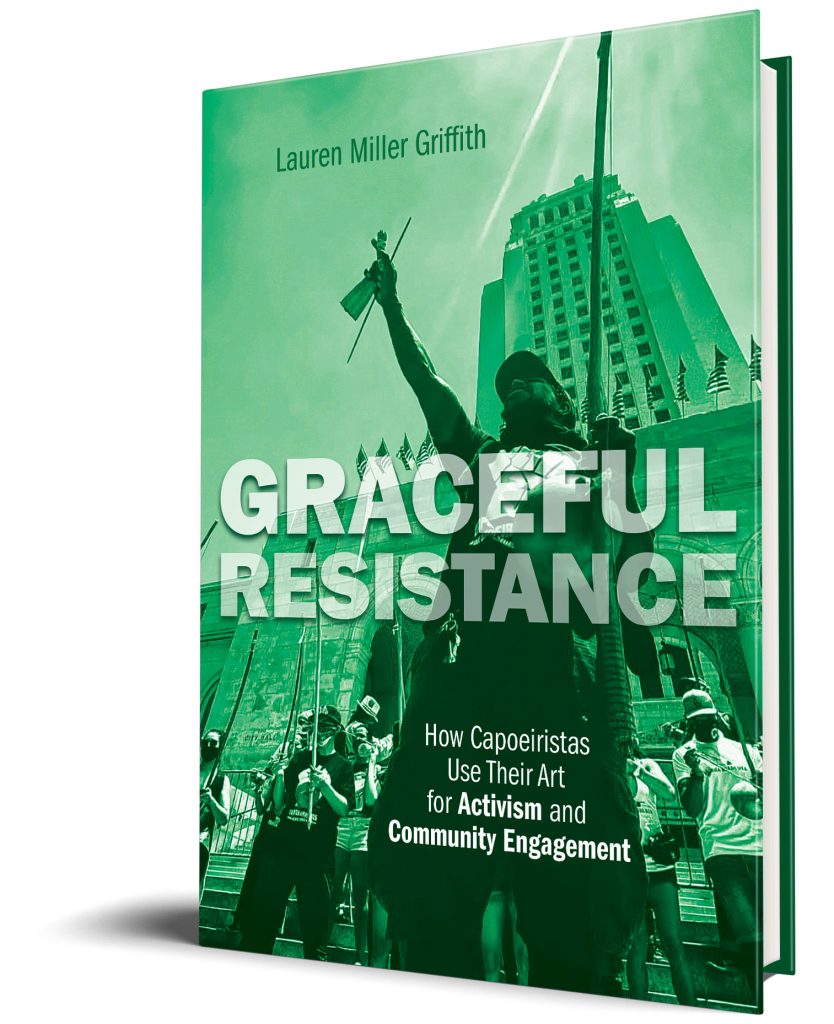

Lauren Miller Griffith, author of Graceful Resistance: How Capoeiristas Use Their Art for Activism and Community Engagement, answers questions on her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I have been studying capoeira in one form or another since I was an undergraduate in the early 2000s, and I have witnessed an explosion of scholarship within this area, so much so that we might actually be able to refer to ‘capoeira studies’ as a legitimate field of study, situated of course within the broader field of martial arts studies. However, I felt like no one was really talking about the social justice aspects of capoeira, which have been very present in the groups of which I have been fortunate enough to be a part. I didn’t necessarily set out to study social justice per se, it kind of came to me as I was chasing another idea. In my previous work, I developed a theoretical lens that I call apprenticeship pilgrimage. This refers to the travels one might make in pursuit of her craft, which ideally put her into a more central position within the social field. Such quests involve both physical and social goals, becoming a better practitioner at the same time that one gains social standing and legitimacy. As I reflected on my earlier work, I realized that most of the apprenticeship pilgrims I met studying capoeira in Brazil were white. I wondered why this was. Was it a matter of economics, or did Black capoeiristas already feel a sense of legitimacy given their connection to the Diaspora? In the very first interview I did on the topic, however, my interlocutor made an off-handed remark that really got to me. He said there aren’t many all lives matter folks in the roda, which I interpreted as a political statement about who participates in capoeira. As I pursued this line of inquiry, I came into contact with many people across the U.S. who are using capoeira for a variety of social aims. I felt like it was a timely topic to pursue, especially given the rise in social awareness and activism that has accompanied recent political shifts in our country.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

One of the things that I think capoeiristas will find most interesting is that no single style or lineage seems to be more socially engaged than any other. Within capoeira studies, we have become very used to the diametric opposition of the angola and regional/contemporary styles that it is almost taken for granted that these divisions are real. I expected to find that practitioners of the angola style would be more engaged in social issues both because of the particular mestres (masters) who have taken leading roles in internationalizing this style and because practitioners are more apt to stress their art’s connection with Africa (and by extension, enslaved Africans’ attempts at resisting oppression in colonial Brazil) than are practitioners of the other styles. However, I found many examples of socially engaged groups across the stylistic spectrum. I was also deeply impressed with the leadership roles American teachers are assuming within this social field. Whereas in my earlier work I talk a lot about the hierarchical structure of the field and the legitimacy of Afro-Brazilian men within capoeira, when I turned my attention to questions of social justice—which resonate strongly with the foundational ethos of capoeira—I saw so many U.S. practitioners who are taking leading roles in articulating the moral obligations capoeiristas today have to their communities.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I want readers of this book to start thinking more deeply about the implications of how we spend our leisure time. I think for too long, leisure has been dismissed as something spurious. Hobbies are not a waste of time; in fact, the time we invest in engaging with others who share our commitments outside of work may be some of the most transformative hours of our lives. And I think that this is increasingly important to talk about as ‘hustle culture’ seems to be pushing us to commoditize every moment of our lives. Capoeiristas very often describe what they do as an art of resistance. Typically, this is a reference to the enslaved Africans in colonial Brazil who continued training martial arts as a means of surviving and perhaps escaping (either literally or metaphorically) their bondage. But one of my interlocutors raised another possibility. She said that merely engaging in leisure within a capitalist society like ours is a form of resistance. Taking advantage of the international network of capoeiristas and couch surfing while traveling rather than staying in hotels is another form of resistance. Opting out of the madness of making every free moment productive is a form of resistance. This is not to ignore the very real economic pressures that have made it hard for many people to survive on a single source of income, but it is a realm in which some people are choosing to question the taken for granted assumptions of our current socio-economic system.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

Getting to interview such an inspiring group of capoeiristas was perhaps the most rewarding part of the process. Working with their words is an incredible gift, and I loved hearing them in my mind as I read and reread the transcripts from our conversations. But as far as the actual publication process goes, I’d have to say that working with the reviewers’ feedback was incredibly stimulating. It was also humbling to see the places where I assumed my meaning would be clear, but it clearly was not. I also enjoyed working with the copy-edits. As strange as that may seem, it was so much fun to get down to the granular level with someone who really understands the nuances of the English language to see where my writing could be improved.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

Follow the questions that keep eating away at you. Even if you can’t understand what it is that keeps bringing a question back to your mind, it is probably because there is something interesting there that needs to be resolved. Also, be flexible. Had I stuck with my original idea for this project, I don’t think I would have had half the opportunities that I would up with after following my interlocutor’s lead. Also, persevere. Although I began research for this book in 2016, the bulk of my writing took place during 2020. This was a horrible time to try and get anything done. Not only were we dealing with an unprecedented global health event, but I had a newborn at home (along with a kindergartner). It would have been easy to give up, but I felt like my interlocutors’ stories needed to be told, and they needed to be told against the backdrop of what was going on in the world at that particular moment.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

When I’m reading for fun, I like to get wrapped up in fast-paced, psychological thrillers. Recently I’ve been reading more short stories, which fit into my hectic life and are a real treat to discuss with friends who have also read them. I also just finished Empathy Exams based on a colleague’s recommendation, which was inspiring, provocative, and humbling all at the same time. When I’m thinking about my craft as a writer, I enjoy books like Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, and as a runner, I always enjoy a good running memoire like Mina Valerio’s A Beautiful Work in Progress.

Lauren Miller Griffith is an associate professor of anthropology in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work at Texas Tech University. She is the author of In Search of Legitimacy: How Outsiders Become Part of the Afro-Brazilian Capoeira Tradition.