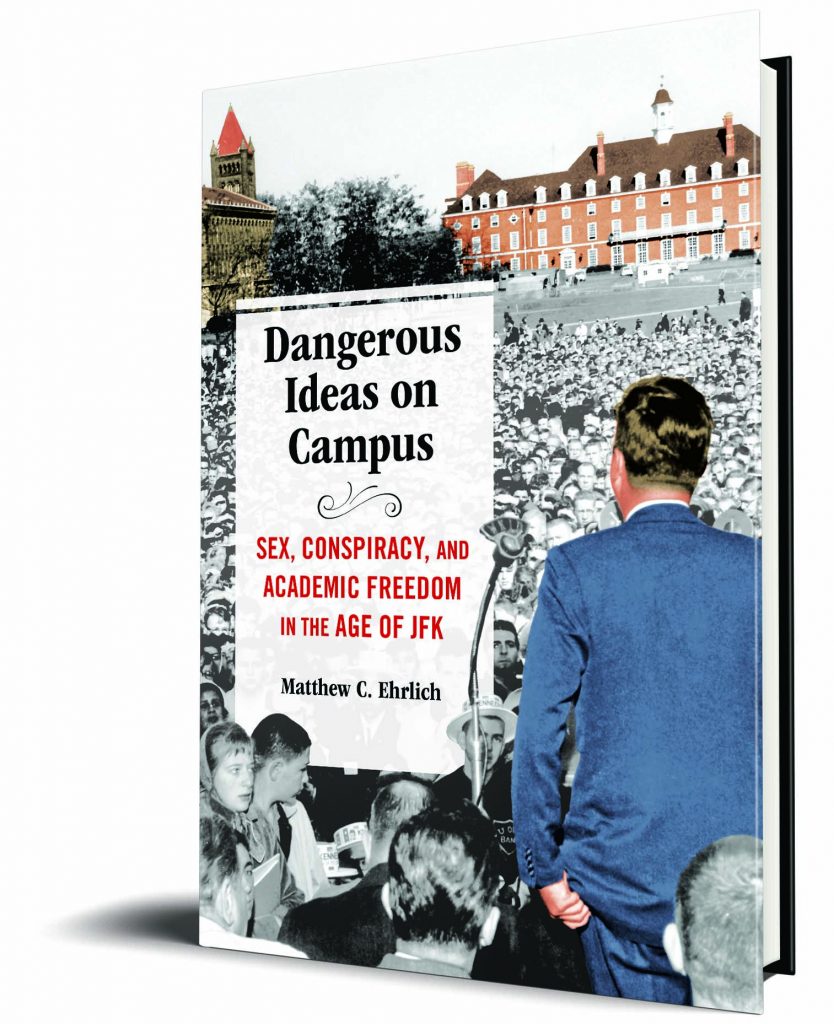

Matthew C. Ehrlich, author of Dangerous Ideas on Campus: Sex, Conspiracy, and Academic Freedom in the Age of JFK, answers questions on his scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from his book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I came to it in a roundabout way. I was the child of college teachers, and I covered higher education as a reporting beat while majoring in journalism in college. I then was a news producer at four university-based public radio stations before working as a full-time journalism professor for 25 years, mostly at the University of Illinois (U of I). With that background, I began researching how the news media over time have covered controversial subjects related to higher education. Premarital sex was an especially contentious topic in the early 1960s; everyone from Margaret Mead to Gloria Steinem was writing about it in the press. That in turn pointed me to the case of Leo Koch, a U of I biology professor fired in 1960 for writing that it was OK for students to have sex before marriage. His case prompted the American Association of University Professors to censure the U of I and pressured the university into strengthening its academic freedom protections. One of the beneficiaries was another U of I professor named Revilo Oliver, who triggered a furor just after John F. Kennedy’s assassination by claiming that Kennedy had promoted an international communist conspiracy. I was reluctant at first to write about Oliver given that he was a vocal white supremacist and anti-Semite. But I finally decided that addressing the Koch and Oliver cases together would make for a stronger book with broader relevance to what we’re going through these days, including controversies over academic freedom and sexual consent on campus plus conspiracy-mindedness in our politics and culture. Focusing on the two professors and other individuals at the Illinois campus—including Roger Ebert, who was then a U of I undergraduate—also enhanced the book’s human interest element, which appealed to the ex-journalist in me.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Henry Reichman, Joan Wallach Scott, and several other scholars have written studies of academic freedom that proved quite helpful, and John Thelin’s histories of US higher education also were very useful. Beth Bailey’s Sex in the Heartland is a historical overview of changing sexual mores at a Midwestern public university; I drew on that book extensively. Thomas Milan Konda’s Conspiracy of Conspiracies provided good historical context about conspiracy theories and the far right. Beyond that, though, I turned to novels. Growing up as the child of college teachers and then working for years at universities gives you a close-up, warts-and-all view of higher education. You experience the frustrations firsthand even as you also come to see that caricatures of professors as wild-eyed radicals indoctrinating their sheep-like students are silly. Fiction often does a better job of capturing the day-to-day realities and foibles of academic life than non-fiction does, so I reread Jane Smiley’s Moo along with Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members and The Shakespeare Requirement in hopes that a bit of their spirit might rub off on my writing.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I discovered that Revilo Oliver and his wife Grace had indirectly worked toward getting Leo Koch fired. They had fed information to an archconservative Chicago minister about purported subversives at the U of I, including Koch; the minister then used that information in launching a letter-writing campaign calling for Koch’s dismissal. I also discovered that people had the same gripes and worries about college students 60 years ago that they still have today. Popular magazines regularly ran stories charging that students were coddled, frivolous, and fragile. Students fired back that their elders had messed up the world, and they, the younger generation, were going to have to live with the consequences. That was all before the era of student revolt later in the 1960s. It’s a reminder that older people have long fretted about younger people and that being young has always been stressful.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

There’s no point in minimizing the substantial challenges that higher education now faces, not to mention the challenges that democracy and the planet in general face. But there’s also no point in being nostalgic for an idealized past that never existed. Universities, and public universities in particular, always have faced political and financial pressures; what faculty and students say and do (or what people think they say and do) always has angered certain individuals. The Koch and Oliver cases make that clear: they sparked outrage toward the U of I at a time when it desperately needed more public funding to support an enrollment surge driven by the baby boom. At the same time, it’s worth remembering that worst-case scenarios do not invariably come to pass. Had you asked people in the early 1960s at the height of the Cold War how likely it would be that we would make it through the next six decades without nuclear warfare erupting, I’m guessing you would have encountered considerable skepticism. We still have the capacity today to make better choices and work toward better outcomes, and higher education can be an important means to those ends.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

Miriam Shelden, a longtime dean of women at the U of I, told a meeting of the U of I’s Moms Association in 1964 that universities were centers of “yeast and ferment.” As she put it, “the university is not a quiet backwater; it is a throbbing, stirring place” where “ideas are debated, where students try to sort out their own philosophies, where students rebel, where allegiances to social justice are pledged.” That’s still what a university should be, even if sometimes it makes some people nervous. There always have been people apprehensive or hostile toward such a vision of a university. But Shelden said that we should “be not afraid. Yeast and ferment produce good bread, and from the university will go forth good students.” Such sentiments might sound naïve today (though Shelden—who fought long and often frustrating struggles on behalf of women in higher education—was hardly naïve). Regardless, the process of yeast and ferment endures on college campuses, and that is all to the good.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

Like some other people, I watched a lot of TV after the pandemic first hit, everything from Small Axe and I May Destroy You to Ted Lasso. The show Derry Girls probably made me as happy as anything else did during that time. I’ve also enjoyed watching sports ever since they returned, even though my hometown of Kansas City couldn’t repeat as Super Bowl champs. Other than that, I’ve gradually resumed travel as circumstances permit, and I’ve also resumed visiting archives to do historical research, which always is fun for me. (Writing is rarely as much fun!)