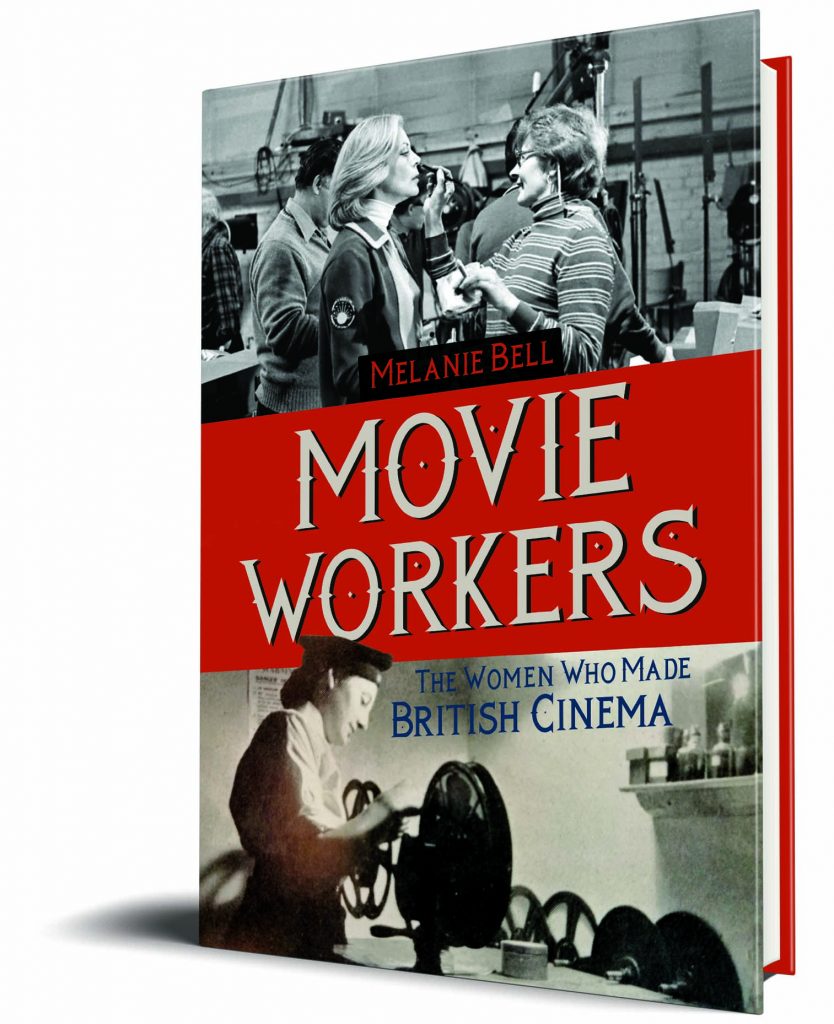

Melanie Bell, author of Movie Workers: The Women Who Made British Cinema, answers questions on her scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways in her book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

The absence of a nuanced understanding of women’s contribution to the histories of British movie-making frustrated me. As a feminist scholar, I understood that this absence was the result of gendered assumptions which were being made by employers, trade unions and subsequently historians about the ‘value’ of women’s labor in film production. Most women in sound era cinema were employed in what were commonly known as ‘below-the-line’ roles, as continuity ‘girls’, wardrobe mistresses, production secretaries, editors, negative cutters and animation assistants; roles that were deemed ‘non-creative’ by male-authored commentary and subsequent film histories which privileged the director role. I wanted to challenge this idea that women’s work in below-the-line roles was ‘non-creative’ and move the argument forward to develop a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of how women’s technical skills and aesthetic sensibilities were central to the success of the British film industry.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

I am indebted to the strong tradition of feminist film historiography that has built up over the last twenty years, in particular to the work of Shelly Stamp, Jane Gaines and Christine Gledhill amongst many others. Erin Hill’s, Never Done: A History of Women’s Work in Media Production (2016) is a pioneering text of women in sound era cinema and foregrounds questions of gender and historical media production in rigorous and engaging ways. I have also been inspired by scholars such as Kate Fortmuller, who has worked tirelessly ‘at the [labor] margins’ for many years, producing excellent scholarship on gendered labor and politics in the media industries. The interdisciplinary nature of this book took me to feminist archiving and the ideas of Kate Eichhorn (The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order, 2013) and Sara de Jong and Sanne Koevoets (Teaching Gender with Libraries and Archives: The Power of Information, 2013) have fueled my passion for thinking critically about the intertwining of gender and knowledge institutions.

Sue Harper and Annette Kuhn are critical influences because of their work on gender and cinema. Sue’s Women in British Cinema (2000) broke new ground in history-writing on British film-making, whilst Annette’s Dreaming of Fred and Ginger: Cinema and Cultural Memory (2002) changed the way film scholars thought about oral history as evidence. Both, in different and complementary ways, have significantly influenced my thinking on questions of gender and film.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

How seemingly unprepossessing sources (archival fragments, trade labor records, anecdotes and oral histories) can offer a window onto a rich and varied work history. A key example of this came to light when I was researching the role women played in the Service Film Units during the Second World War, especially the Royal Naval Film Section. Whilst it was widely acknowledged that they had worked as editors, negative cutters and projectionists, I was delighted to uncover records which revealed the full extent of women’s involvement which ranged across editing, photography, continuity and location work, the preparation of technical drawings, and the construction, painting and lighting of film sets. A picture of women’s multi-faceted contribution to war service emerged where their labor as carpenters, painters, draftswomen and model-makers was essential to the success of the creative team. I was able to recreate this history through archival fragments and seemingly ‘mundane’ trade labor records, and this and similar discoveries validated my methodology and empowered me to write these women’s histories with confidence and authority.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

This book dispels the myth that women’s work in below-the-line roles in film production was non-creative. This myth suited the needs of employers and unions, enabling them to hold down wages for women and channel them into ‘supporting’ roles, but it didn’t reflect the reality of women’s work on the studio floor, on location, and in editing suites. Here women were part of a team that worked together to achieve a collective end, participating in a process which had a number of interlocking, co-dependent elements. Whether working as wardrobe mistresses, continuity ‘girls’, art director assistants or editors, women had not only technical skills but the aesthetic sensibility to deploy them and make creative decisions in the service of a shared understanding of what the film was trying to achieve. Approaching women’s work through this lens helps us unlearn the histories of film production which have marginalized women’s labor, re-valuing it from a fresh perspective.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

That whenever and wherever films are made, women have had a creative hand in the process. I hope readers can grasp the multiple forms and variant ways through which women made a major contribution to film production in Britain during the 20thC, and how we can draw together their work histories into a collective picture which enables us to reframe concepts of ‘creativity’ and ‘value’ in ways which are genuinely inclusive and exciting.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

There’s so much quality television right now that it’s hard to fit it all in. My current favorite is Call My Agent (Dix pour cent) that focuses on the professional machinations and dramas of a Paris-based talent agency. It’s smart, stylish and cinephilic with laugh-out-loud moments, and makes me long for a trip to Paris. Other recent favorites were Money Heist (La casa de papel), a Spanish crime drama, which fed my sartorial fascination with boiler suits, and the Swedish bank-heist comedy A Very Scandi Scandal, revolutionary is giving lead roles to two middle-aged women who take on the patriarchy and win.

For fiction I like the detective genre, and its mainly female-authored novels I return to time and again, especially PD James, Josephine Tey and Sara Paretsky. I like the mental agility that their complex plotting demands, and that their detectives are workaholics largely unencumbered by domestic responsibilities; I like my fiction to be escapist!