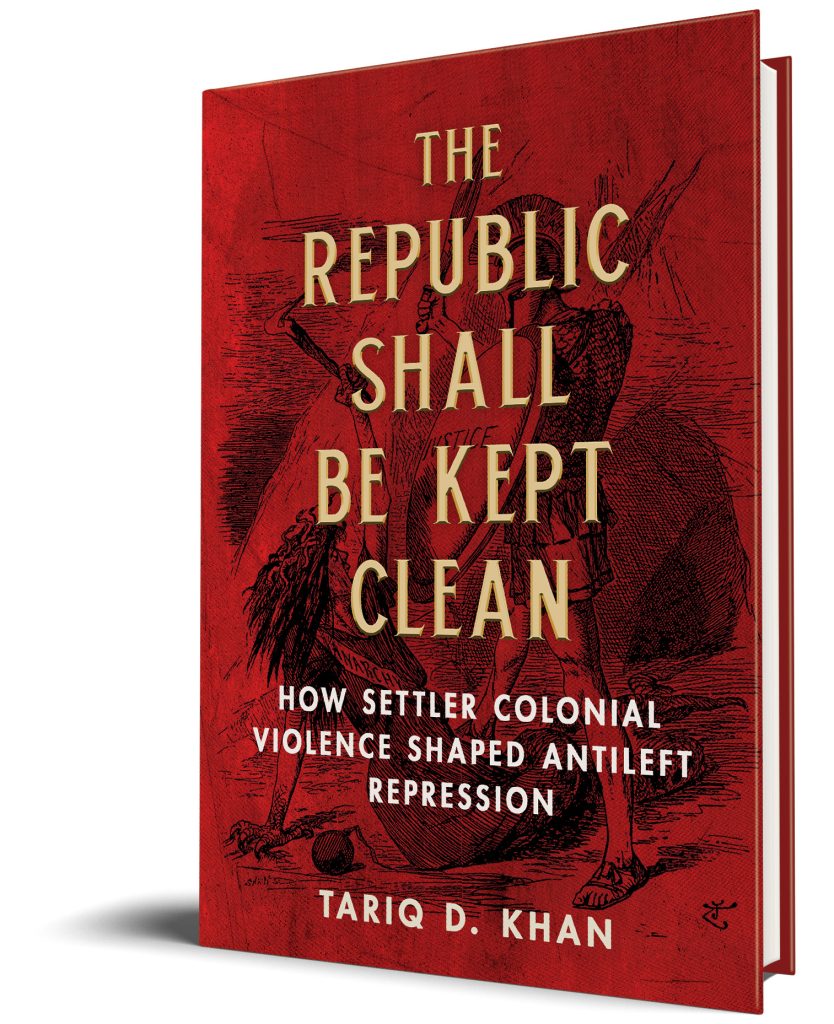

Tariq D. Khan, author of The Republic Shall Be Kept Clean: How Settler Colonial Violence Shaped Antileft Repression, answers questions on his new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I started thinking down these lines nearly twenty years ago, in the hyperpatriotic cultural atmosphere of the post 9/11 U.S. so-called “war on terror.” As the United States, under President George W. Bush, recklessly intensified its imperialist violence against people in the Middle East and South Asia, ordinary patriotic whites within the United States increasingly committed hate crimes against people they perceived to be Muslim. The state also simultaneously increased surveillance and repression of Muslim communities within the United States. It seemed clear to me even then that outward imperialism, state violence at home, and white supremacist extralegal violence were all connected. One of the early connecting threads that stood out to me was the rhetoric of “civilization versus savagery.” Mouthpieces of the state, corporate-owned media, and ordinary Islamophobic/racist white citizens all used that same kind of rhetoric to justify their violence. So this started as a small project about the colonialist discourse of “civilization versus savagery,” but grew into what became this book.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

There have been so many interesting discoveries, but since I’ve been teaching history of psychology courses over the past year, my discussions in this book on the relationship between the mind sciences and counterinsurgency policy stand out as particularly important. For example, why did an immigration law that policymakers crafted for the specific purpose of banning anarchists from the United States also ban people diagnosed as “idiots” and “epileptics”? And what did any of that have to do with US gender politics and genocidal colonial violence? Primary source research reveals that things that may seem unrelated on the surface are deeply intertwined. That has implications for social movements that are fighting for equality: the need for a radical approach that connects issues and attacks underlying systems.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope to contribute to people unlearning, or at least critically examining, patriotism. This is something that the 19th and early-20th century anarchists I wrote about understood well: that in the context of a violent imperialist state built on stolen land, genocide, slavery, exploitation, and ongoing injustice, patriotism is not virtuous. It is in fact harmful. Patriotism holds even progressive historians back from asking the questions, making the kinds of connections, and coming to the kinds of conclusions that justice and truth demand. Patriotism leads well-intentioned social movements down dead ends, and it has been nothing but a stumbling block for the labor movement. It mystifies minds and misleads people to consent to very evil policies. I think of policies such as Trump’s child separation policy, which led to extreme child abuse and ongoing trauma, and how many ordinary patriotic U.S. citizens it took — within federal, state, and local agencies, as well as private contractors — to carry out that evil program. It wasn’t just Trump and his vile racist advisor Stephen Miller who made that happen. It was thousands of ordinary patriotic citizens of different races, ethnicities, and religions, doing their jobs and obeying orders. And now in the face of climate crisis, the need to think and act globally as an interconnected human family, beyond the narrow confines of states and militarized borders, urgently requires us to dispense with patriotic myths.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

Archival research was the most interesting because the archives are full of fascinating surprises which open doors to new avenues of historical inquiry.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

Yes, do it. Especially in US labor and working-class history, we need more historians to recognize the centrality of settler colonialism to US culture and politics.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I like to skateboard, play the upright bass, and walk in the woods with my dogs.

Tariq D. Khan is a lecturer in the history of psychology at Yale University.