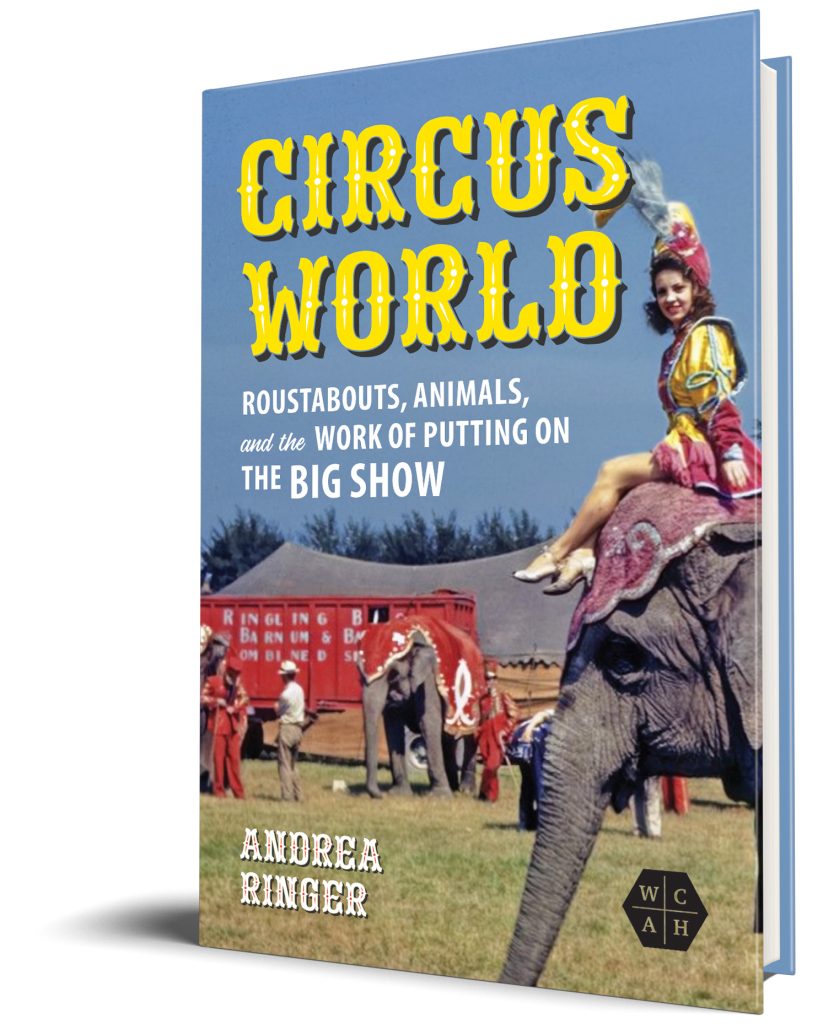

Andrea Ringer, the author of Circus World: Roustabouts, Animals, and the Work of Putting on the Big Show, answers questions on her new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

In December 2013, I had this idea to write a labor history of the circus. The following May, I visited my first circus archive, the Robert Parkinson Library at Circus World in Baraboo, Wisconsin. That visit squashed my fears about not being able to find enough sources on the topic. It also provided an unrivaled archival experience. I went there knowing I’d feel good about the trip if I could find a handful of references to the AFL strikes in the 1930s. But when I showed up the archivist had pulled entire folders just on the strikes. The library and archive are on the grounds of the former Ringling Brothers winter quarters. I spent days copying files about circus folks who lived in the circus world a century ago, and then would step outside to take lunch and breaks among the sights and sounds of the circus world. Parked circus wagons and trains were just outside, as were elephants (no longer there as of 2023) awaiting the afternoon show in the smaller big top tent. The barn that had held elephants between seasons during the golden age of the shows now held museum panels. It was an immersive experience and shifted my focus from a much smaller story about just a few workers to a history that considered the entire circus world.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I found the tidbits about animal experiences to be the most compelling stories. It was sort of an eye-opening realization to see them mentioned in programs, newspapers, or people’s memories as standalone workers, not necessarily associated with a person. In one reference, I found Babe the elephant, who worked for the Barnum show for decades. As a performer, she was a member of the herd, probably indistinguishable from the other elephants in the eyes of audience members. But she also had to make her way from the circus train to the circus lot, as did all the animals and people in the circus world. This was done in the public eye and she reportedly remembered the route without help. Of course, the circus could have and probably did capitalize on this idea to convey ideas of a happy workforce, but the story does get at real instances of occupational knowledge among animals. I’ve carried this story with me into subsequent work and it’s shaped how I approach animal labor history.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I hope people reimagine who counts as a worker. The circus has such dominant names attached to it. Even a century later, P.T. Barnum and the five original Ringling Brothers are household names as the architects of the circus. But the workforce was diverse in almost every way imaginable. Kids, adults, people from dozens of countries, high-paid performers, low-wage workers, animals who performed, animals who did grunt labor—it was all on the circus lot on any given day. I think it’s easy to see the roustabouts from my title as workers, but all those other categories are explained away as something else—performers, celebrities, to captive animals. All these workers were contracted in one way or another to perform work for the same employer. They each collected a paycheck, or somebody else collected a paycheck for their labor.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

Looking at photographs was so fun and I saved my final choices for the very end. After getting reader reports, I decided to add the section introductions that are each written around a single photograph. Those last-minute deep dives felt like a kind of capstone to the book, and they helped me conceptualize the circus world in spaces on and off the lot.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

Share your work along the way! None of this book was written in isolation. I felt a little stuck in my manuscript when I started my job. I sat on the writing for about a year. I?knew what chapters I still needed to write but didn’t really know where to start. Honestly, I was intimidated to fully immerse myself in animal studies and be in conversation with those brilliant scholars. Of course, those chapters ended up being the most fun and rewarding to write, mostly because I wrote all of them in workshops. Getting real-time feedback from folks whose work I admired gave me the confidence I needed to add to that field. But it was also so helpful to get feedback from folks who aren’t in my field but were still willing to chat about circus history. Participating in interdisciplinary writing groups has been helpful while writing this book.? So, I suppose my advice is share your work widely!

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I enjoy podcasts. I usually listen to HISTORY This Week with Sally Helm while I run. When We Talk About Animals out of Yale is also a really great podcast. It takes me so long to get through a TV show because my kids are at the age when they just don’t want to go to sleep. But The Bear is my favorite show. Nashville really is the best place to listen to live music, so that’s always one of my favorite things to do. Even my neighborhood has a little summer concert series. I always feel like I’m reading something that I need to read, but I take time to read a book that won a major book award every year without taking any notes in the margins. I’m just reading to enjoy it.

Andrea Ringer is an assistant professor of history at Tennessee State University.