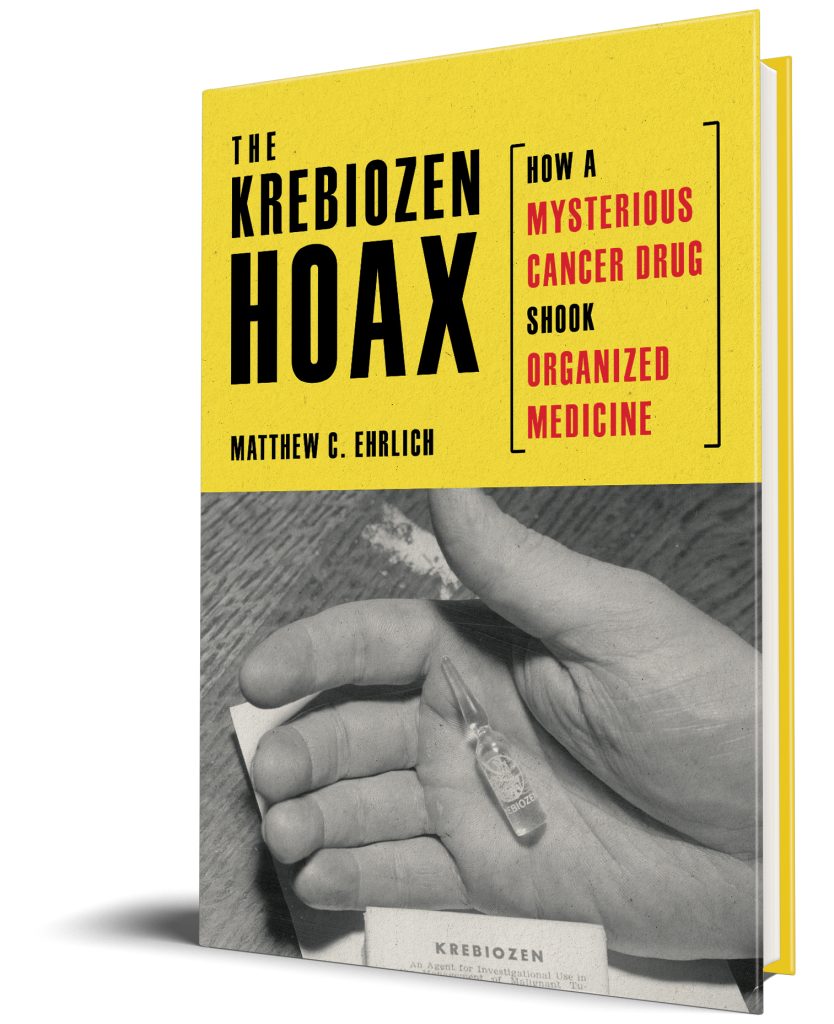

Matthew C. Ehrlich, author of The Krebiozen Hoax: How a Mysterious Cancer Drug Shook Organized Medicine, answers questions on his new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

The impetus came from my previous book, Dangerous Ideas on Campus, which focused on events at the University of Illinois (U of I) while David Henry was president. Henry had become president after his predecessor George Stoddard was forced out in 1953 during an uproar over an ultimately discredited cancer drug called Krebiozen. I decided that the Krebiozen affair would make a good book of its own. U of I vice president Andrew Ivy had dragged the university into the affair by sponsoring the drug, which had been introduced to him by a mysterious Yugoslav doctor named Stevan Durovic. Stoddard had bitterly opposed the drug and ended up losing his job. Eventually the US government’s medical agencies would get involved, and there also would be dramatic legislative hearings on Krebiozen plus a months-long criminal trial. I thought that all of this would make for an interesting story with parallels to the controversies that higher education, science, and medicine are confronting today.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

President Lyndon Johnson gave his personal backing to a test of Krebiozen to try to demonstrate its value, even after the Food and Drug Administration and the National Cancer Institute had both officially pronounced the drug as worthless. US Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois persuaded Johnson to support a potential test at a time when the president in return needed Douglas to help push an ambitious legislative agenda through Congress. As it turned out, the Krebiozen test never happened; Andrew Ivy and Stevan Durovic failed to meet any of the agreed-on conditions for a test to proceed. I learned about all this from the private papers of Douglas’s aide Howard Shuman in the U of I Archives. Shuman had worked hard to arrange a Krebiozen test, and he poured out his frustrations with Ivy and Durovic in memos that ended up in his papers. (The senator and his aide never went public with what had happened, probably because it would have greatly embarrassed everyone concerned.)

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

People don’t necessarily turn to an unproven medicine because they’re dumb or anti-science. When Andrew Ivy first embraced Krebiozen, his scientific reputation was impeccable. Paul Douglas, the drug’s most prominent political proponent, had been called the conscience of the Senate. Silent Spring author Rachel Carson took the drug, and a number of the medicine’s backers had previously pushed for civic betterment and social justice. They supported Krebiozen for a variety of reasons. Some of them resented the medical establishment, which they felt cared more about money and power than about healing. Or they admired Ivy, who argued that we didn’t know enough about cancer to shut down any kind of research into potential treatments. In Carson’s case, she had had negative experiences with doctors who had lied to her about the extent of her cancer. She tried Krebiozen only to see if it might make her feel a little better or live a little longer (it did neither). In short, there were plenty of good intentions and legitimate concerns behind Krebiozen’s rise. Unfortunately, Ivy and other supporters of the drug refused to accept overwhelming evidence that it did not work, except perhaps in certain instances as a placebo. As is often the case with quack remedies, other people shamelessly exploited Krebiozen for political or economic profit while destructively undermining trust in mainstream science and medicine.

Q: Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting?

Every part of the process is interesting as well as challenging—mostly in a good way! The cliché about how “it takes a village” certainly applies to writing and publishing a book. That begins with the research, which typically relies on archivists to facilitate things. It continues through the acquisition and peer review processes and then through the copyediting and final preparation of the book. I’ve been fortunate over the years to work with many good, supportive people. Even when I’ve received a critical review from a reader recruited to judge the merits of a manuscript, the review has been constructive enough to help me strengthen the manuscript.

Q: What is your advice to scholars/authors who want to take on a similar project?

There’s no one-size-fits-all advice for someone undertaking a historical study, but these are the suggestions I’ve offered in the past: Try to tell a good story with compelling characters. Avoid presentism, but remember that history always speaks to the present. You have to address the “who cares?” question—why should we care about this particular subject in this particular moment that we’re living in right now? I also find it helpful to remember that history offers useful perspective. It reminds us that we don’t live in uniquely awful times and that nostalgia for an allegedly lost golden age never gets us very far. And it also reminds us that although notions of continual human progress are suspect, at certain moments in the past, we have demonstrated the capacity for working toward just ends and improving our common lot.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

My reading tends toward non-fiction stories about history and popular culture along with the occasional novel. I watch sports and movies on TV, plus a number of programs on too many different streaming platforms. Listening-wise, I’ve been enjoying the new “Illinois Soul” service through Illinois Public Media.

Matthew C. Ehrlich is professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He has previously published five books including Dangerous Ideas on Campus: Sex, Conspiracy, and Academic Freedom in the Age of JFK and Kansas City vs. Oakland: The Bitter Sports Rivalry That Defined an Era.