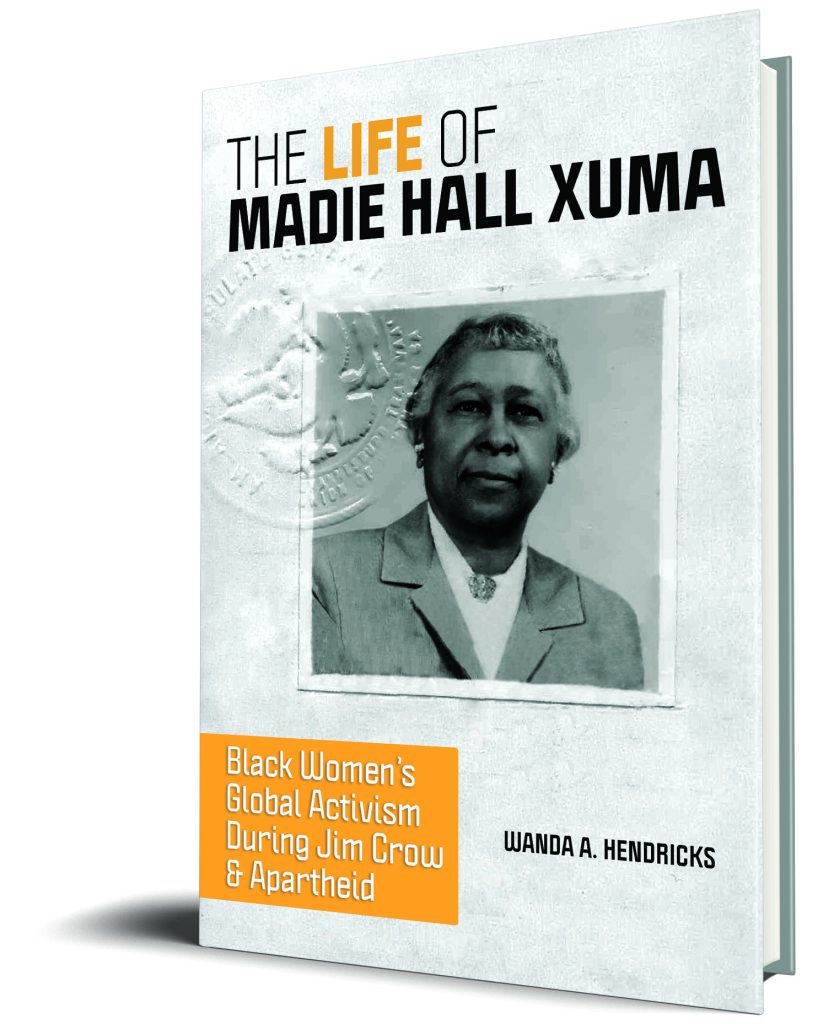

Wanda A. Hendricks, author of The Life of Madie Hall Xuma: Black Women’s Global Activism during Jim Crow and Apartheid, answers questions on her scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from her book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

This biography has been decades in the making. I wrote this book because Madie Hall Xuma was one of the most prominent Black women in the world yet few Americans know who she is. Even as a scholar of Black women’s history, I didn’t have a clue about her activism in her hometown of Winston-Salem, North Carolina during Jim Crow and on the global stage during and after World War II. So, when I met Hall Xuma a few years before she died, she was simply the lady who lived next door to my relatives although, I had taken a college course on the history of South Africa, a place where she resided for more than two decades, and written a paper on one of the most prominent figures in the history of the country, Alfred Bitini Xuma who was president of the African National Congress from 1940 to 1949. Intrigued by a brief conversation with her when she mentioned something about South Africa, I did a little research and discovered that she was Xuma’s wife. I never forgot her and often wondered how I could not know who she was and how the erasure of this prominent Black American woman from history had occurred. (Unlike in America, she remains well known in South Africa.) Then as so often happens in life, my life changed. I entered a Ph.D. program, immersed myself in studying the evolving field of Black women’s history, wrote a dissertation on the social and political activism of Black women in Illinois and secured an academic faculty position. After my first book was published, I decided to write the first biography of a prominent late nineteenth and early twentieth century Black female intellectual and activist who, like Hall Xuma, few Americans knew. It was only after those two publications and believing that I now had the research and the technical skills to write a global biography that I circled back to Hall Xuma. I wish I could say that I planned this whole process but I cannot. I am, however, open to the possibility that maybe Hall Xuma did. Nearly forty years after I first met her, I am very happy that this story of Hall Xuma’s life and activism will finally be out in the world.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

I owe so much to my great aunts Alma Hendricks Cardwell and Nola Hendricks Lash and cousin Barbara Lash for first nurturing my curiosity and encouraging me to explore a world beyond the one I knew; and second for introducing me to Hall Xuma. I also owe a debt to the Black female academic scholars like Darlene Clark Hine, Deborah Gray White, Jacqueline Rouse, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Wilma King, Evelyn Higginbotham, Sharon Harley and Elsa Barkley Brown who worked so tirelessly to make Black women’s history an academic field of inquiry and who forced me to ask different questions of the archived sources and the history as it has been written to understand how to uncover the stories of Black women.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I was amazed to discover how adventurous Black women were, how much they traveled and how engaged and linked they were with women across the United States and throughout the world. Madie Hall Xuma either took a train or drove a car throughout the South and up and down the eastern seaboard during Jim Crow. She relocated to Florida and New York and created community in both places. She even vacationed in Cuba, a place I discovered was a favorite destination for African Americans. More significantly she traveled nearly 9,000 miles from the United States to South Africa by ship in the middle of a war. It took three weeks. She returned to the United States after World War II on a Pan American Airlines flight which took her only a few days. She also flew to such places as Switzerland, Lebanon, France, England, Sweden, the Netherlands, Mexico, Ghana and a host of other countries. She was not alone. Other Black American women who engaged with Hall Xuma, like Mary McLeod Bethune, Dorothy Height and Charlotte Hawkins Brown, were also on the move. As important is the fact that Hall Xuma found a common mission and comradery in national Black women’s organizations such as the National Association of Colored Women. She also was welcomed by women’s organizations in South Africa and in one of the largest organizations for women and girls in the world, the World Young Women’s Christian Association, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. Likewise, members of the National Council of Negro Women forged a connection with the National Council of African Women in South Africa and the Women’s International Democratic Federation, founded in Paris, France. As a scholar of Black American women’s history, African American history and American history, this discovery excited me in ways I can’t quite articulate at the moment.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

One of the most important myths I hope to dispel is that the genre of biography is only about the subject being written about. Biography is the only medium through which we see and intimately experience how family structures, historical time period, events, organizations, politics and economics shape a life on a micro level. For example, we often talk about the concepts of Jim Crow and sexism in broad, sweeping and sometimes vague terms but it is only through the lens of Hall Xuma that we see how both systems actually shaped the lives of her mother and father as they engaged in the upbuilding of Black Winston-Salem, impacted her educational aspirations as she entered both segregated HBCUs in the south and the integrated Columbia University in New York City and denied her the opportunity to become a doctor like her father because she was female. Through her we see in real time how the oppressive systems of Jim Crow and apartheid were initially implemented and evolved over time. She reveals to us how she felt as the slow, arduous and painful process of the dismantling of Jim Crow in the United States was occurring at the same time that she was enduring the implementation of the draconian measures of oppression under apartheid and the steady march toward the white supremacy republic Afrikaners envisioned. There is no other genre that can portray such intricate detail except biography.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

I am hopeful that readers will see that the activism and work of women, particularly that of Black women, has always had a connection to geopolitics. Racism and white supremacy around the world were geopolitical issues. Colonialism was a geopolitical issue. The refugee crisis after WWII was a geopolitical issue. Having adequate housing and food were geopolitical issues. The rebuilding of Europe was a geopolitical issue. Nuclear weapons and fears of world annihilation were geopolitical issues. Activist women all over the world engaged in these discussions and raised money to actually rebuild communities. Moreover, they created their own international organizations and attended sessions at international organizations like the United Nations to ensure that they were included in deliberations about how the world should function. So, after reading this book readers should be able to see how gendered descriptive definitions matter in the ways in which historians and history determine who and what is important. The feminized terms “social welfare” and “domestic housekeepers” that often describe women’s work (I used the terms in the book) were as essential to the human race’s survival and as politicized as a masculinize term like “head of state.”

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I read as much as I can both for entertainment and to learn something new. I am currently enjoying mystery stories by Black writers. I am pretty sure that I have read most of the “In Death” series published by J. D. Robb. I mix those up with the collection of essays in books like To Turn The Whole World Over: Black Women And Internationalism and the new biographies of people like Mary Church Terrell, Sophonisba Breckinridge, John Lewis, etc. I went to Switzerland for the first time in 2019 and had expected to continue a quest to explore new travel destinations. Since the pandemic began, I haven’t been in an airport and have not ventured more than one hundred miles by car from my home. So, for now delving into a good book that transports me to other destinations is the only way I am traveling. I watch some television but am rather fickle about what I like. Lately it has been “In the Heat of the Night”, “Matlock” and “Perry Mason” but I truly enjoy Masterpiece movies on PBS. And I try to listen to some good R&B music from Anita Baker, Luther Vandross, etc. everyday.