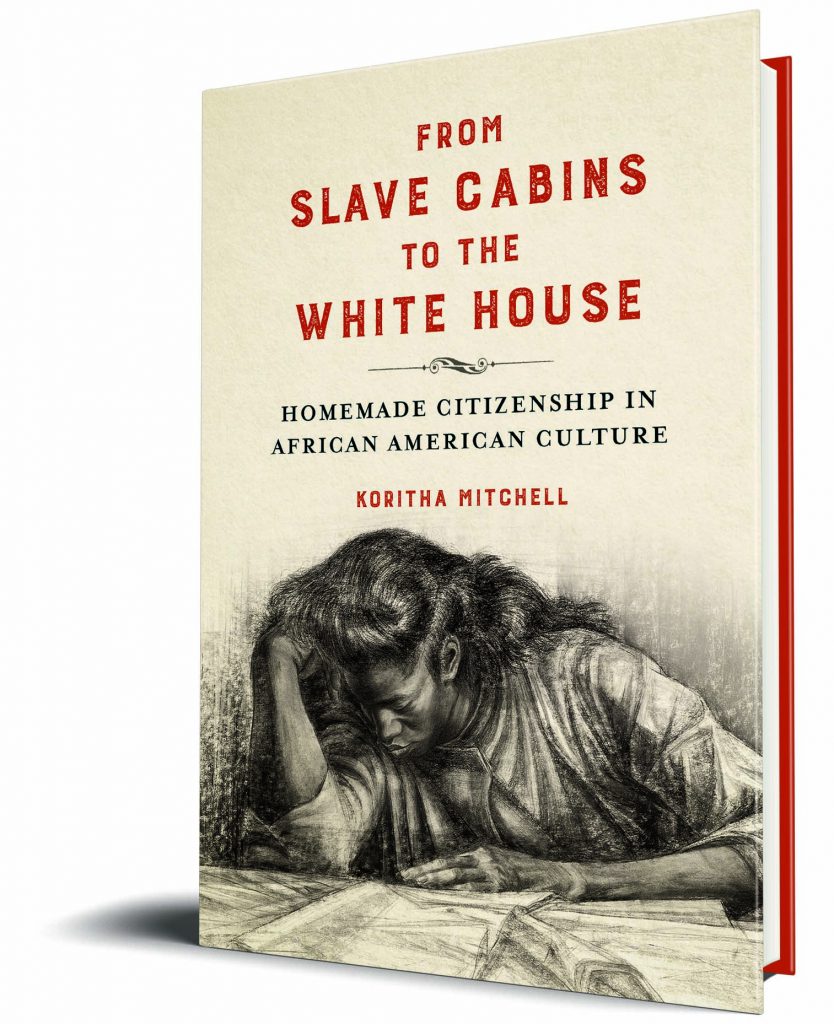

Author, Koritha Mitchell, of From Slave Cabins to the White House: Homemade Citizenship in African American Culture answers questions about her influences, discoveries, and dispelling myths about African American culture.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

What became clearest to me because I researched and wrote Living with Lynching is that black success beckoned the mob, and African Americans recognized that fact! If Black people pursued accomplishment despite knowing it would make them targets, then didn’t it make more sense to read their literature through the lens of success rather than assuming it was shaped by resistance and protest?

Once I realized how much Black people had been identifying white people’s investment in interrupting Black people’s journeys toward achievement, I saw that scholars had focused on protest mostly because white supremacy had suggested that white people make the world and everyone else must respond to it. In fact, African American authors understood that white people kept re-making the world in their image because their brutality never did the job of dehumanizing and suppressing others’ greatness. White mediocrity (or worse) kept shining through, kept proving they were anything but superior.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

Without question, the ancestors shape this work. I am simply trying to be faithful to the evidence they left—evidence that gets clouded only because we approach it with perspectives that have been skewed by mainstream ideas we have absorbed despite our best efforts to maintain community-centered clarity.

At the same time, earlier scholars of both cultural studies and history have been influential because the foundations they laid made these insights possible. I think of it in these terms: Brittney Cooper’s book Beyond Respectability (also published by UIP and shepherded by editor extraordinaire Dawn Durante) could reveal all that was not explained by foundational black feminist frameworks because those frameworks had been so field-shaping. That is, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s “the politics of respectability” and Darlene Clark Hine’s “dissembling” had inspired so many studies for the past several decades that it helped Cooper see what wasn’t accounted for.

Likewise, I owe a debt to all earlier scholarship because the ubiquity of a protest/resistance approach allowed me to see what was in Black cultural production that those theoretical frameworks did not fully notice.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I went into this project believing that reading through the lens of success would reveal what had not been seen before in canonical works by African American women, but I was still surprised at what most struck me upon reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved that way. Focusing on Black women’s definitions of achievement exposed the novel’s investment in the accomplishment of choosing, for oneself, one’s object of love. The United States has robbed Black women of the ability to choose a romantic partner—even as it has forced children upon them, children fathered by both black and white men. Writing Beloved in the 1980s, Morrison grappled with the reverberations of that robbery as her text revisits enslavement and the early years of freedom for (self)emancipated Black women, not just Sethe but also Baby Suggs and others.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

I want readers to unlearn the belief with which Western societies have bombarded us all, that protest is the most logical lens through which to view the creative works of all marginalized people. In truth, dominant culture pounces on marginalized populations to convince them of that which dominant culture cannot convince itself: that it deserves to be dominant.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

That’s easy: African American literature and art do not exist primarily to respond to whiteness and its relentless violence. White violence is a reaction to black achievement, a fierce attempt to destroy black achievement and obliterate all signs that it ever existed.

As I did by including Islamophobia and ableism (for example) in my most comprehensive account of know-your-place aggression, I hope this book will lead readers to prioritize success when interpreting art by individuals and populations that are trans, queer, Asian American, Latinx, or differently able. I hope it becomes standard to read the literature and art of all marginalized groups with an eye toward their investment in achievement rather than with an obsession about how they respond to the forces arrayed against their freedom and joy.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

My absolute favorite television series are Showtime’s Billions and HBO’s Insecure. I have been ahuge fan of Issa Rae since she created Awkward Black Girl on YouTube. I wrote about it on my first blog, long before everyone else jumped on the bandwagon. Watching her journey has been an absolute joy!

As I think about my love for Issa Rae’s work, and Awkward Black Girl and Insecure represent only a fraction, I understand even more why The Black Guy Who Tips (TBGWT) is my favorite podcast. I appreciate the insistence upon combining an awareness of how diverse Blackness is with irreverence and even raunchiness.

I found TBGWT in 2016, as I finished the first draft of From Slave Cabins to the White House.

Very little went my way as I tried to bring this book to completion over the past 4 years, but TBGWT, its hosts, and its community-minded audience have been with me every step of the way. I have emotional ties to this podcast for too many reasons to name. However, it’s worth noting that the hosts, Karen and Rod Morrow, describe their creation as a comedy talk show with the motto, Nothing’s Wrong If It’s Funny.

In a world that brutalizes Black people in myriad ways, I take seriously the need to find humor in the not-at-all fictional horror that comes with being blessed to live another day.