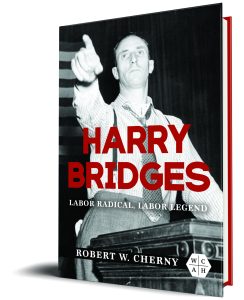

Robert W. Cherny, author of Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend, answers questions on his scholarly influences, discoveries, and reader takeaways from his new book.

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

In 1985, I was approached by Nikki Bridges, the wife of Harry Bridges, and asked if I would be interested in writing a biography of Harry. I had previously written a biography of William Jennings Bryan and had enjoyed the challenge of tracing one person throughout a lifetime. I had some knowledge of Harry’s leadership of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) at the time, but, as I think about it in retrospect, I knew surprisingly little. I met with Harry and Nikki, and we all agreed that I would undertake the project. I understood at the time that it would be a major research project, covering much of the 20th century and events in both Australia and the U. S., but I really had no idea just how extensive my research would have to be, including research in archives all across the US, in Australia, and in Russia. In the end, it took more than ten years to complete the archival research and more than ten years to receive Bridges’s enormous FBI file. And I could not have anticipated that, by the time I had collected nearly all my sources, university responsibilities would delay my writing. This project began in the mid-1980s. Most of my research was complete by the late 1990s, but completing my writing had to wait until I retired from teaching.

Q: Who were your biggest influences?

I had read and appreciated John Garraty’s The Nature of Biography, but I cannot call it my “biggest” influence. When I began my research, Harry and Nikki were still alive, as were many of those who had worked with Harry, so I began my research with many interviews. My interviews with Harry, Nikki, and many members of the ILWU certainly influenced my understanding of that union and of Bridges’s role within the union. However, my archival research confirmed that historians must always be just as critical of their human sources as they are of their archival sources.

Q: What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing your book?

I cannot point to a single thing but to several. Bridges’s FBI file yielded a number of interesting discoveries, including the FBI’s burglary of Bridges’s lawyer’s office and the FBI’s criticism of the Immigration Service’s investigations and prosecutions of Bridges. The files of the Communist Party (CP) of the U. S. in the Russian State Archive for Social and Political History in Moscow produced many interesting discoveries, especially about the CP in San Francisco in the early 1930s and about Bridges’s relationship to the CP at that time. Archives in Australia led me to conclude that Bridges had told stories about his youthful seafaring experiences that could not have happened in the way that he described them.

Q: What myths do you hope your book will dispel or what do you hope your book will help readers unlearn?

As I state in my introduction, there is more than one story about Harry Bridges. One story, told many times, is that he was a member of the Communist Party, and that that is the most important thing to know about him. Another story, also told many times, is that he was the victim of an elaborate frame-up to prove that he was a Communist and therefore liable for deportation, that he was the victim of repeated federal prosecutions that had as their intent the elimination of an effective labor leader, and that those are the most important things to know about him. Both stories have elements of truth in them, but neither is the most important story about Harry Bridges. The most important story is that he was a remarkably effective leader of a remarkable union.

Q: What is the most important idea you hope readers will take away from your book?

There are more than one, and I cannot single out “the” most important.

One has to do with the nature of Bridges’s union leadership. When Bridges died in 1990, one journalist observed: “The fusion of leadership with the rank and file was Bridges’ genius, and his power.” The longshore caucus institutionalized this fusion of leadership and membership: frequent meetings of a hundred-plus elected delegates from every longshore local to engage in free-wheeling discussion of the contract, their concerns, and their goals. The ILWU also institutionalized that fusion through large negotiating committees, with elected representatives from all major locals, and sometimes by “fish-bowl” negotiations, with the entire longshore caucus observing and able to raise concerns with the negotiating committee. Bridges always and repeatedly insisted that any settlement be approved by vote of the entire membership–and, at times, by a super majority. In later years, when lauded for his accomplishments, Bridges’s reply was always the same: the credit belongs to rank and file.

Another Is not unique to my book by any means, but has to do with the importance of understanding the political context of legal proceedings. Bridges was investigated by the US Justice Department’s FBI and Immigration Service; he spent seventeen years in various hearings, trials, and appeals, three of which went to the US Supreme Court.

Another, also not unique, is an understanding that underlies all serious historical research: history is complicated. There are rarely simple answers to questions. For example, those who want me to give a simple yes-or-no answer about Bridges’s relationship in the CP will always be disappointed, because the answer is complicated and varies from one time period to another.

Another is the importance of archival research in addition to interviews and oral histories.

Q: What do you like to read/watch/or listen to for fun?

I enjoy mystery and espionage novels. Le Carré was, of course, the great master of such novels. Reading the best authors of such novels is somewhat like engaging in a research project in history. One starts with a question—who did it?—and the protagonist has to search through many different sources to find an answer, and, in the best of these, the answer can sometimes be quite ambiguous. Although I like to watch the film or BBC adaptations of such novels, I have always found the novels to be more complex and therefore more satisfying.