As University Press Week enters its second decade of celebrating excellence in university press publishing, Next UP has been chosen as the theme for this year’s event.

The theme highlights the dedicated work performed by those in the university press community to seek out, engage, advance, and promote the latest scholarship, ideas, best practices, and technology. University presses are incredibly creative and resourceful, working in concert with their authors, readers, and institutional and business partners, and Next UP reflects that spirit of constant learning, adaptation, and evolution.

This week, we’ll be featuring exciting innovations from our journals department, presenting an interview with a UIP author, and announcing changes to one of our series. Make sure to check out the other posts in the UP Week blog tour and browse the #NextUP gallery here.

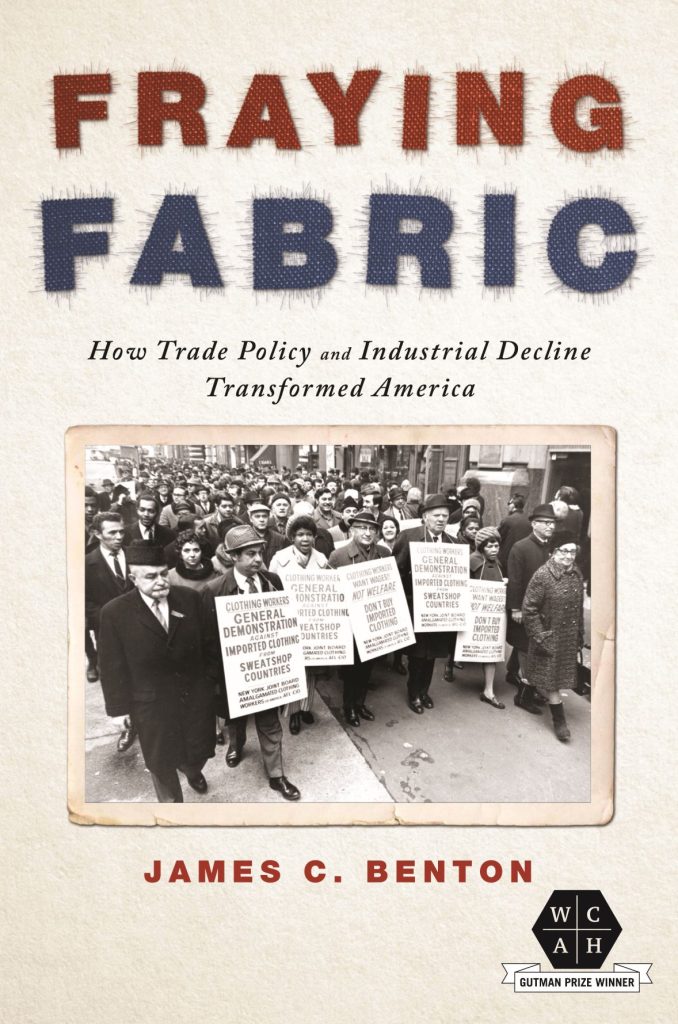

In this blog post, we interview James C. Benton, author of Fraying Fabric: How Trade Policy and Industrial Decline Transformed America, winner of the 2017 Herbert G. Gutman Prize for Outstanding Dissertation.

Why did you decide to write Fraying Fabric?

I set out to write this book as a way of understanding more deeply the rapid employment decline of the U.S. textile and apparel industries, specifically between 1995 and 2005. In the 1960s, these industries employed one in seven U.S. manufacturing workers; as late as 1974, they employed more than 2 million manufacturing workers. By the beginning of 2021, both industries employed just 202,000 workers. During this time, as numerous mills closed there and in other communities across the nation, many pointed to the North American Free Trade Agreement as the primary culprit for the loss of this industry.

The disappearance of these industries dramatically changed the nature of my home community in western North Carolina, in which cotton cultivation and cotton textiles were both significant contributors to the local economy. Generations of my family were involved in this economy, through farming and sharecropping cotton, and, later, through working in the mills (I worked in a textile mill part time between high school and my sophomore year in college). I knew that trade agreements like NAFTA were part of the picture but there was more to the story.

After making a career change from journalism to the nonprofit sector, I returned to night school to pursue a master’s degree. It was there that I began investigating this question of economic change. My master’s thesis was a case study of the federal Trade Adjustment Assistance program and its use in one city, Kannapolis, North Carolina. In 2003, the city’s main employer, Pillowtex Corp. (the former Cannon Mills) declared bankruptcy, throwing more than 7,600 employees out of work.

That study gave me an understanding of, among other things, the textile industry and trade policy, and my advisers urged me to go further in my academic work. In turn, that led me to pursue a doctorate in history, where I studied workers in four textile and apparel unions — the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, the United Textile Workers of America, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and the Textile Workers Union of America — and their opinions on trade, along with business executives and presidential administrations. In time, I focused on U.S. trade policy and its effect on these industries between the New Deal and the early 2000s.

What is the most interesting discovery you made while researching and writing this book?

I would say there are two equally interesting discoveries I made during research and writing. The first is that workers were deeply vocal about the effects of trade policy on their jobs and industries, and though they sometimes used protectionist and racist language in defending their jobs, they saw a danger in lowering trade barriers that their counterparts in business, government, and at times, even their own leaders in labor, could not or did not see. One of the most vivid examples in the book was the opposition to the 1930s trade deals under the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Program by woolen workers in Massachusetts; they, along with their counterparts in other industries there and across the country, saw a danger in lowering tariffs to expand trade with other nations. As has been the case for decades now, the trade agreements tended to get far more attention than the needs of workers who were at risk of being displaced.

The second interesting discovery was especially critical to the story that unfolds in the book: the almost universal assumption of American economic, political, and industrial dominance that extended a quarter-century, from the end of World War II to the dawn of the 1970s. To be sure, this assumed dominance is understandable — the United States stood alone as an economic powerhouse at the end of the war — but this assumption continued apace as the rest of the world caught up through the 1950s and 1960s. While individuals in government, labor, and business saw the effects of increased international competition, those concerns were often swept aside — a pattern that continued until, suddenly, in the late 1960s, international competition affected many other domestic manufacturing sectors and had become too evident to avoid.

Both discoveries, to me, point to the importance of a strong voice for American workers in the daily and long-range functions of our economy. The events documented in Fraying Fabric show what happens when workers, and by extension, the labor movement, lack a strong voice on economic issues alongside leaders in business and government. Workers and labor leaders fought valiantly to keep these industries viable in the face of foreign competition. Yet the textile and apparel unions could not get the labor movement to act definitively on trade until competition began to challenge other industrial sectors. Simultaneously, the U.S. labor movement lost power on economic issues as government, and later, business, became more ascendant in terms of planning economic policy. We are seeing this play out again now, during the Covid-19 pandemic, as workers struggle for rights and respect in their workplaces and fight to organize at companies including Amazon and Starbucks. Whatever economic future we face in the United States, workers and labor must be a part of that conversation if we are to move toward an economy that works better for all. Otherwise we will continue to have an economy that delivers massive rewards for some at the expense of the rest of us.

Which part of the publishing process did you find the most interesting? Least interesting?

As a former journalist, the most interesting thing was the much longer lead time for a book! I was accustomed to daily deadlines in the newspaper industry, but the process wound up taking a few years because I took two and a half years to do additional research and make several revisions to the manuscript. The least interesting part of the publishing process, for me, was the permissions process for photos, as well as the indexing. They are necessary, but tracking down the provenance of photos and compiling the index couldn’t compare to the excitement of archival research.

What innovations, if any, are you looking forward to seeing in labor studies?

I hope my book inspires more labor historians to look into trade to understand more deeply the importance of workers and the labor movement in working to address economic concerns. We have seen this through works on labor feminism, and of course the labor movement has constantly engaged economic issues from wages and hours to pensions, unemployment, workers’ compensation, and so forth. But I think the field is ready for deeper historical study of the effects of economic policies in a global economy, and how to ameliorate the negative effects of these policies on workers. I also hope this work would encourage more study of industrial decline that focuses on the period before the plant shuts down or the industry enters a death spiral. When I began this research, the study of deindustrialization almost exclusively focused on single towns, companies, factories, etc., affected by decline. I think there is more work ahead for historians to tell the full story of the ways in which twentieth-century globalization affected many domestic industries and led the United States in the direction it’s now going, economically, politically, and socially.

What is your advice to scholars/authors in your field?

Don’t give up! This book was not the easiest to write, and I discovered early on in my research there was no “smoking gun” that one could point to as a culprit for all the bad things that happened in terms of deindustrialization and trade. Rather, this was a story where conditions seemed to be all right until they reached a point where they weren’t—where the challenges of trade really began to mount for workers and industries.

I set out to study one of the more complex industries in the United States, and often had to search through numerous collections to find material. Trade issues often took a back seat to other issues over the period I covered in my book; sometimes the documents I located on trade sometimes were not voluminous. Because of the lack of unionization in the southern branch of the textile and apparel industries, I did not have a great deal of material from southern workers on trade issues. Even with these obstacles, I feel the documentation I found (often in individual locals’ records and in letters to political leaders) did offer a representative sample of workers’ voices on trade and the efforts to address trade and international competition in textiles and apparel. This work took nearly fifteen years and spanned almost two dozen archives across the United States, and I could easily have visited two dozen more in researching this book, were space and time limitations not a consideration.

This is a complex story, a story that defies easy categorization. It neither defends nor blames free trade or protectionism for the issues we now face. Likewise, any reader seeking a single political figure or party to point to as the culprit on trade policy will be disappointed. This was—and I cannot stress this enough—a collective failure by business, labor, and government that was decades in the making. This failure has produced a trade policy that helps businesses but doesn’t adequately aid affected workers and which has set in motion a “beggar-thy-neighbor” approach by which states and localities use tax abatements to raid companies from one location to another. Our trade policy, sadly, has dovetailed with the increasing radicalization of segments of the American population who feel they are being left behind economically at the same time they are losing social status. This radicalization, combined with social media, American society’s obsession with celebrity and wealth, and increasing gridlock in our political systems, helped produce Donald Trump in 2016.

Where do we go from here in terms of trade policy that provides better support for affected workers, in terms of worker voice, in terms of building a fairer, more inclusive economy? One possible direction might be the embrace of the “just transition” model in building a green economy, where workers benefit from new jobs — especially affected workers whose jobs are connected to fossil fuel extraction. Another answer might be found in economic models like worker-owned cooperatives. Another may be found in political reform of trade policy. But whatever the response is, it must find a way to prevent workers from being left behind. Rethinking trade policy is a matter of economic fairness, but in contemporary United States society, it must also be considered a model of social insurance that guards against both the continued radicalization of segments of its population and the rise of fascist politics.

Join James C. Benton and Robert Parmet for a virtual event celebrating the release of Benton’s new book on December 5 at 1pm EST.

Register here: https://bit.ly/FrayingFabric